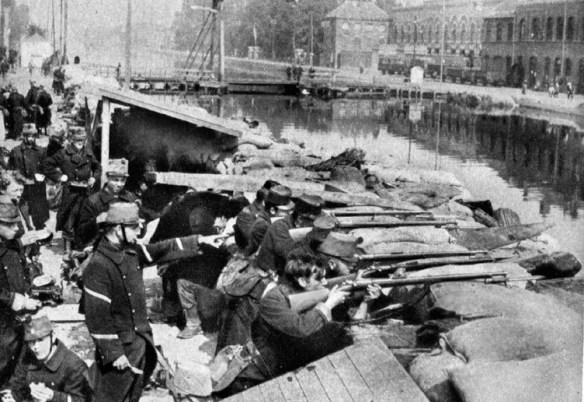

Belgians manning a defence line at Antwerp.

Antwerp defence system included an area of countryside that could be flooded by opening sluices on the banks of the River Scheldt.

The port of Antwerp was designated as the National Redoubt and consisted of four defensive lines:

- A ring of 21 forts approximately 10 to 15 km outside the city.

- A secondary line of resistance of twelve older forts around 5 km outside to the city.

- A group of two forts and three coastal batteries defending the river Scheldt.

- Pre-prepared areas that could be flooded.

On Saturday, 10 October 1914 Admiral von Schroeder, Antwerp’s new military governor, and General von Beseler, commander of the siege troops that had captured the fortress, watched as the siege corps marched in review, celebrating the capture of the Belgian National Redoubt. The most noteworthy thing about that day was the absence of civilian bystanders. Antwerp was practically empty of its citizens, most of them having fled before the fall of the city. Buildings were smashed and the smoke from the petroleum tanks burning at Hoboken could still be seen rising above the city to the west. Antwerp had become a dead city.

The forts were also dead and empty, their defenders having either escaped to the west, surrendered to the Germans or fled to Holland, where they would be kept in internment for the remainder of the war. It seemed as if it was all over for Belgium. Since 4 August Belgium’s three fortresses had been crushed by German siege guns and the remnant of the Belgian army was fleeing to the French border. But the loss of the city and the forts was not the end. In fact, the Belgian army escaped to the west only because the forts and defenders held out long enough for them to do so. Thanks to the Belgian and British defenders of Antwerp, the Belgian army would live to fight on and to hold a small piece of west Flanders that would cost the Germans (and the Allies) hundreds of thousands of casualties over the next four years. The Germans captured the city but they lost the Battle of Belgium.

On 16 August the last forts of Liège fell. In short order the German First and Second Armies advanced across Belgium. On the 17th the Belgian government fled from Brussels to Antwerp. The following day King Albert moved his army headquarters from Louvain to Mechelen, 25km from Antwerp.65 On the same day the Belgian army, minus the 4th Division at Namur, withdrew from its concentration point on the Gette and headed to Antwerp. When it seemed as though Namur was about to fall, General Michel pulled the 4th Division out of the fortress and it eventually made its way via France to Antwerp. The Germans marched triumphantly through Brussels on 20 August and began to move south into France. General von Kluck detached and left behind III Reserve Corps, along with the German Naval Division, to keep watch on the Belgian forces at Antwerp, and to guard his lines of communication to Liège.

King Albert and his commanders ordered a number of sorties from Antwerp to disrupt the German forces guarding the city. If they succeeded, perhaps the Belgians could move further across the country and disrupt the German lines of communication. Regardless, the goal was to cause havoc. The first sortie occurred on 24 August in the direction of Mechelen. The Germans easily held their position and pushed the Belgians back. On 9 September a second sortie was launched towards Vilvoorde and met with greater success, this time reaching a point 16km from the fortress line. On that same day, realizing the danger Antwerp posed to the German flank, and needing to remove the obstacle blocking the seizure of the channel ports, Kaiser Wilhelm II ordered its capture. A relatively ineffective third sortie took place on 27 September, at the same moment as the siege of the fortress began.

On 27 September the Battle of Antwerp began, just as the other fortress sieges had, with a heavy bombardment. The following day King Albert received reports that this wasn’t just a demonstration of strength but an all-out offensive to capture the city: large bodies of German reserves were observed assembling at Liège to move towards Antwerp.

There was a general belief among those in the army and the government, and perhaps also the Belgian population, that Antwerp would never fall to a besieger. It was one of the largest fortified places in the world, with numerous forts. On the map the defences seemed to be formidable and impregnable, but the only map that mattered to the Germans was the one that told them the distance between their heavy siege artillery batteries and their targets: Antwerp’s obsolete ring of forts.

Fortress Antwerp was built by the Spanish in 1567, as the northern bastion and major port city of the Spanish Netherlands. The Spanish surrounded the city with a bastioned wall fashioned with lunettes to the north, east and south, the Scheldt river acting as a major obstacle to the west. A large crown work called in later years the Vlaamsch-Hoofd or Tête de Flandres defended the left bank of the Scheldt. Two large citadels flanked the eastern and western ends of the enceinte where it met the river. This was what King Leopold’s commission of government and military officials found when he ordered a study of Belgium’s defences. In 1859 the decision was made to create a national redoubt and to improve the defences of Antwerp so it could serve as a place of refuge if Belgium were attacked. The army would retreat, along with the government, into the city, safe behind the ring of forts, and await rescue by the allied powers according to their terms of guaranteed neutrality.

Between 1861 and 1871 General Brialmont directed the construction of eight large forts along the southern flank of the city, between the outskirts of Wijnegem and Hoboken. These were simply called Forts I to 8. Their purpose was to extend the fortress perimeter in order to keep enemy guns out of range of the city. Flood zones were developed to protect the outlying portions of the perimeter. However, after the Torpedo Shell Crisis of 1885, and because the town had outgrown Brialmont’s inner ring, these defences had become obsolete. To counter the increased range of enemy guns, a second ring of forts was built further out from the city.

Due to financial constraints, only a few works were actually constructed. Two forts were built to the south at Walem and Lier, and a defensive dyke that could be controlled to create a flood zone was added on the left bank of the Scheldt, covered by Forts Zwijndrecht and Kruibeke. To the north Fort Ste-Marie was built and Forts St-Philippe and La Perle were modernized. Each of these forts was built of brick. Fort Steendorp was the first to be built using brick with a layer of concrete added on top. As funding became available in the late 1880s, Fort Schoten was built to the northeast, along with the small Fortin of Duffel to guard the Brussels–Antwerp railway. These were built entirely in non-reinforced concrete. The ring was completed in 1893 with the construction of Forts Oorderen, Berendrecht and Kapellen.

A new round of construction was planned in 1900 but was delayed for funding reasons until 1906. Thirteen new forts and twelve permanent interval redoubts were added. The forts were polygons, surrounded by a water-filled moat, with the entrance reached by a bridge across the moat. These forts more closely resembled the configuration of Brialmont’s earlier models,66 Forts 1 to 8, than the more modern Forts of the Meuse at Liège and Namur. The latter forts were built on high ground and had a central redoubt surrounded by a dry ditch. The terrain around Antwerp was flat and low-lying, with a high water table, so no ditch would stay dry for long.

By 1914 Antwerp was one of the largest fortresses in the world, with a circumference of some 95km. It consisted of thirty-five forts and twelve redoubts. The guns in the older forts were placed in open air batteries, but the new forts were equipped with 15cm, 12cm and 7.5cm guns in revolving steel turrets. The approaches to the forts were defended by 5.7cm rapid-fire guns in turrets. Like the forts of Liège and Namur, the Antwerp forts were built to withstand shelling from 21cm siege guns. Unfortunately the German siege corps brought much larger guns to use against the forts in 1914, including the 42cm and 30.5cm howitzers. Many of the forts were incomplete when the Germans approached in early September 1914.

The Opposing Forces at Antwerp

Belgium had six divisions to defend the fortress: a total of 80,000 men. Four divisions were tasked with defending the perimeter, with one division in reserve; the weakest division – the remnant of the 4th Division from Namur – was placed at Termonde to guard against a German crossing of the Scheldt. One cavalry division with 3,600 men was located southwest of Termonde to guard the lines of communication between Antwerp and Ghent. Finally, the forts were garrisoned with 70,000 fortress troops. General de Guise, who had left Liège in July, was in charge of the entire force.

The German siege corps was commanded by General Hans von Beseler and had a total strength of about 125,000 men. It consisted of III Reserve Corps, IV Ersatz Division, one division of Marine Rifles from Marine-Korps-Flandern, one Bavarian Division, the 26th and 27th Landwehr Brigades, one brigade of siege engineers, one brigade of light artillery and nine extremely powerful heavy siege mortar batteries. The heavy artillery batteries included the following:

- KMK Battery 2: Hauptmann Becker with two 42cm Gamma

- KMK Battery 3: Hauptmann Erdmann with two 42cm M-Gerät (which saw action at Liège)

- SKM Battery 1: Hauptmann Neuman with two 30.5cm mortars (which saw action at Liège)

- SKM Battery 4: with two 30.5cm mortars

- SKM Battery 5: Hauptmann Sharf with two 30.5cm mortars

- SKM Battery 6: Hauptmann Buch – one 30.5cm mortar

- Festungsartillerie-bataillon Batteries 7 and 9, each with two 30.5cm Austrian mortars.

The Battle for Antwerp

Great Britain played a significant role in the battle for Antwerp. In fact, had it not been for the assurances of Sir Winston Churchill, there might not have been a battle in the first place. In support of his promises, the British sent a Royal Naval brigade and a brigade of Royal Marines – a total of 10,000 men under the command of General Archibald Paris – to Antwerp, although they were mostly raw recruits, poorly equipped and trained, with few, if any combat skills.

On 2 October, a few days into the battle for Antwerp, things were not going well for the Belgians. King Albert notified the British government of his intentions to pull out of Antwerp immediately to prevent his army from being trapped, as it was apparent that the fortress line was breaking and the Allies didn’t appear to be coming to the aid of the Belgians. General Kitchener, the British secretary of state for war, had planned to send British troops to relieve Antwerp, and the French had promised the same, but these forces were still a few days away and would not reach the area in time. Winston Churchill, Lord of the Admiralty, replied that the British would send a brigade of marines to arrive on 3 October. Churchill himself decided to make a visit to Antwerp to reassure his ally, not least because it was in Britain’s best interests that Antwerp hold out as long as possible so the channel ports were not seized by the Germans. Their loss would be a severe blow to the allied efforts.

Churchill worked out an arrangement with the Prime Minister of Belgium, Charles de Broqueville, under which the Belgians would hold out until the Allies arrived from the south. De Broqueville told Churchill he was confident they could hold for at least three more days, possibly more. Churchill assured him that if, in three days, they were not confident they could hold, they were under no obligation to stay and could retreat with Britain’s help: ‘If we can’t help them hold, we’ll help them get out.’ Thus, on the evening of 3 October some 2,000 marines were dispatched by train to Antwerp.

The fortress was far from complete at the start of the battle and the defences were still being organized. Concrete protection around the turret cylinders was not yet in place, and the engineers were obliged to use sandbags instead. Many of the turrets were without guns, and several of those that had guns were missing their firing sights. The forts also had other major construction flaws, in particular the quality of concrete used in their construction. They had been built to withstand 21cm shells, but the Germans had brought 30.5cm and 42cm guns to the front with an unlimited ammunition supply. Even if all the fortress guns had been available, the forward observation posts had not yet been set up so the guns would be firing blind. They also lacked an adequate supply of munitions. Worst of all, the Belgian guns did not have the range to reach the German batteries.

The engineers worked to overcome numerous geographic challenges presented by the region. The city had continued to expand outward, and obstacles blocking the guns’ lines of sight had to be cleared. Churches, farms and trees were levelled to the ground with explosives – nothing that stood in the way was spared. Because the land was flat, once the surrounding structures were cleared away, the outlines of the forts were easily visible to enemy observers. Worse, when the guns fired, they produced black smoke that could be seen for miles.

Preparation of a 100km defensive perimeter line was a monumental task. Interval trenches were dug along most of the perimeter, but they tended to be shallow and poorly organized, and had no bomb-proof shelters. In some places they were little more than gullies. Obstructions were placed across the access roads. Paving stones were pulled up and used as barricades. Miles of barbed wire was stretched along the perimeter and around the defensive strongpoints. Infantry parapets were built up along the streams and canals. Bridges and viaducts were strewn with explosives, ready to be destroyed at a moment’s notice.

The outer ring of fortifications extended three-quarters of the way around the city, beginning on the right bank of the Scheldt north of the city and ending on the left bank to the northeast. The outer perimeter consisted of large forts with permanent redoubts built between the forts to serve as rallying points for the interval defence. The outer ring, beginning on the right bank northeast of Antwerp, below the Netherlands border, was arranged as follows (see Map opposite): Berendrecht Redoubt (a), Oorderen Redoubt (b), Fort Staebroek (1), Staebroek Redoubt (c), Fort Ertbrand (2), Fort Cappellen (3), Fort Brasschaat (4), Dryoek Redoubt (d), Fort Schooten (5), Audaen Redoubt (e), Fort St Gravenwezel (6), Shilde Redoubt (f), Fort Oeleghem (7), Massenhoven Redoubt (g), Fort Broechem (8), Fort Kessel (9). The inner ring consisted of Forts 1 to 8 (23 to 30) and Fort Merxem (31). The Vlaamsch-Hoofd (32) was located across the Scheldt from the town centre.

The fortress was divided into five defensive sectors:

- Sector 1: north – Forts St-Phillipe, Merxem, Cappelen

- Sector 2: east – s’Gravenwezel, d’Oelegem

- Sector 3: southeast – Nethe line near Lier and Duffel

- Sector 4: along the Rupel – Bornem, Liezele

- Sector 5: left bank of the Scheldt and in the area of Waes.

The Belgian army ordered the 1st and 2nd Divisions to Sector 3, while the 3rd and 6th Divisions were kept in Sector 4; the 4th Division occupied Termonde and the 5th Division remained as the general reserve.

The bombardment of the Belgian army headquarters at Mechelen had started on 18 October, as a result of which King Albert moved the headquarters to Antwerp. Once Mechelen was taken, the Germans moved their heavy guns forwards and began shelling the forts. The first German attack was directed against Sector 3. The strategy was to punch a hole in the defences of Sector 3 with the heavy guns, followed up by an infantry attack to cross the Nethe and Scheldt rivers. After that, the breach would be widened by the destruction of the forts in Sectors 2 and 4.

After the capture of Mechelen, the Germans advanced all along the line of Sectors 1, 2 and 4. They occupied Alost on the extreme left and Heyst-op-den-Berg on the right. The siege cannon were moved up into place and would concentrate on the forts in Sectors 1 and 3.

The first targets on 28 September were Forts Waelhem and Wavre-Ste-Catherine, using the 30.5cm and 42cm guns emplaced at Boortmeerbeek, about 10km south of the fortress line, at their maximum optimum range, as well as smaller-calibre guns. The effects were felt immediately in the forts, as the concrete cracked and fumes from the explosives spread throughout the tunnels. The 15cm turret of Fort Waelhem was put out of action and the telephone lines to the fort were cut.

On Tuesday, 29 September the Germans attacked Sector 4, pushing back elements of the 3rd and 6th Divisions some 1,500m from the main line. Then 30.5cm shells started falling on the entry bridge at Fort Breendonck. A German column reached Blaesveld bridge on the Willebroek Canal but was driven back by the defenders.

The bombardment of Fort Waelhem continued at the rate of ten shells per minute. The garrison fought to restore communications with headquarters, and all the fort’s guns remained operational (apart from the 15cm turret destroyed the previous day). The second 15cm turret was targeting the Mechelen–Louvain railway, where enemy activity had been spotted. At 1600 this turret was also damaged and put out of action. The ammunition magazine in the fort was hit and exploded, and seventy-five men inside the fort were badly burned. At 1830 the armoured observation post was struck, meaning the guns had to fire blind. During the night the guns were repaired and they continued firing in what they perceived to be the correct direction.

Fort Wavre-Ste-Catherine also suffered on the 29th. The turrets were destroyed one by one, and the garrison driven out of the shelters. At 1800 the fort was evacuated but the garrison would return later.

Captain Becker, commander of KMK 2, described the effects of the shells on Forts Koningshoyckt and Wavre-Ste-Catherine:

As shown by many photographs, the 42-cm shell was effective against the heaviest armour and concrete of the Belgian forts. As typical of this effect, I recall in particular two hits made by my own battery on the Fort of Wavre St[e] Catherine, in the outer line of forts of Antwerp, on 29 September 1914. On the morning of the 29th I fired with the second piece, the more accurate, at the heavy guns in the armoured cupolas, while using the first piece against the concrete casemates. On this day, I saw my eleventh shot strike fair upon the top of the cupola, where the enemy’s guns were actively firing. There was a quick flash, which we had learned at Kummersdorf [artillery proving grounds] to recognize as the impact of steel upon steel. Then an appreciable pause, during which the cupola seemed uninjured; then a great explosion. After a few minutes the smoke began to clear, and in place of the cupola we saw a black hole, from which dense smoke was still pouring. Half the cupola stood upright, 50 metres away; the other half had fallen to the ground. The shell, fitted with a delayed fuse action, had exploded inside.67

The outlying defences also suffered terribly from the shelling. The interval redoubts and trenches were hit with the same violence as the permanent works. The forts provided supporting counter-battery fire whenever possible, but the forward observers were driven from their positions throughout the day and were no longer able to direct fire against the enemy. It appeared the Belgian defenders in the trenches would suffer the same fate as at Namur: pounded by unseen guns without any means of reply, and driven off their positions by unseen troops.

Despite Churchill’s promises, the Belgian leadership were not confident of rescue by the Allies, who were still 200km away. On the night of the 29th they concluded that since Antwerp was not as impregnable as they had originally thought, the field army should be quickly withdrawn, and saved to fight another day. The field troops were to be pulled back to the Dendre river to await the Allies, who were now approaching Arras. The evacuation was scheduled to begin on 2 October. The army supplies from the Antwerp warehouses would be transported first by rail to Ostend. The rail journey began at the Tête de Flandre on the left bank of the Scheldt, passed through St Nicholas and Ghent, and finally arrived at Ostend. The transports had to cross the railway bridge at Tamise, and to reach that they needed to cross the Willebroeck bridge – within range of the German guns. Despite the danger, the operation was completed under conditions of absolute stealth between 29 September and 7 October. The lines of retreat were defended by the 4th Division, deployed at Baesrode, Termonde and Schoonaerde. The cavalry was moved to Wetteren to guard the left bank of the Dendre, where the field army would take up position on 3 October.