The character of the French and British North American “empires” differed greatly. Although the French did war against the Iroquois, Natchez, Fox, and other tribes, they did not “conquer” New France; they merely paid very high tolls to the Indians for the privilege of exploiting it. Beyond their narrow ribbon of settlement between Quebec and Montreal, or ports like New Orleans and Mobile, the New France “empire” largely consisted of several scores of ramshackle trading posts, often isolated from one another by hundreds of wilderness miles and resentful Indian tribes. None of those tribes thought themselves French subjects and would have been incensed had it been suggested that they were. Nor did they think of the annual goods dispensed by the French traders as “gifts.” Of the goods received from the French, some were exchanged for “rent” and others for furs. The several hundred voyageurs, marines, and missionaries scattered across that wilderness understood clearly that their survival depended on nurturing Indian hospitality and greed, and they became quite adept at doing so by immersing themselves in Indian tongues, customs, marriage, and ambitions.

In contrast, the British had brutally conquered their empire between the Atlantic and the Appalachians with endless streams of settlers armed with muskets, diseases, and ploughs. By 1750, Britain’s 1.25 million American subjects had elbowed aside or eliminated the local tribes and towered over New France’s 80,000 white inhabitants. The British advantage went beyond raw numbers of settlers. British goods were better made, more abundant, and cheaper than those dispensed by the French. With such overwhelming power, the British could afford to be more assertive and less sensitive toward Indians. In doing so, they fired the hatred of most tribes against them, and even the smoldering emnity of erstwhile allies like the Iroquois and Cherokee.

Throughout the 17th century, the conflict between the French and English was waged primarily through competition for the alliances and trade of various Indian tribes. But as New France and the various English colonies expanded in territory and population, their merchants, soldiers, and privateers increasingly skirmished with each other on forest trails and the high seas. The French and English fought five wars for North America-Huguenot (1627-1629), League of Augsburg or King William’s (1689-1697), Spanish Succession or Queen Anne’s (1702-1713), Austrian Succession or King George’s (1745-1748), and Seven Years’ or French and Indian (1754-1763). It was the final war, of course, that proved to be decisive. The last French and Indian War cannot be understood apart from the century and a half of imperialism that preceded it.

Dutch Imperialism

Dutch imperialism split the English colonies. Perhaps no nation has risen from obscurity into a great power more rapidly or struggled for independence longer than the Netherlands, which achieved both simultaneously. From 1569 to 1648, seven provinces of the Spanish Netherlands fought a bloody, seemingly endless war for independence. During those same decades, Dutch merchant and war ships grew ever more powerful along the world’s ocean trade routes. The Dutch established colonies on East and West Indian islands, and on enclaves dotting Africa’s coast. Perhaps the greatest coup occurred in 1628 when a Dutch fleet captured that year’s Spanish treasure fleet and 200,000 pounds of silver. Amsterdam emerged to rival London as Europe’s most vigorous commercial center, and Paris and Rome as a cultural capital.

Like the other great powers, the Dutch increasingly eyed North America as a potential source of wealth and power. In 1609, Henry Hudson sailed up the river that now bears his name, in search of the Northwest Passage to Asia. What he found instead was direct access to the rich fur country of central New York States. Dutch ships annually visited the Hudson River country between then and 1614 when the New Netherlands Company received a three-year monopoly to exploit the region. The Company promptly established Fort Nassau at present-day Albany. When the monopoly expired, the free-for-all among ambitious merchants resumed until the Dutch West Indian Company received a monopoly to the region in 1624. The Company established Fort Orange near Fort Nassau’s ruins. Two years later, in 1626, it founded New Amsterdam on Manhattan Island at the mouth of the Hudson River. Over the next four decades, Dutch settlements spread not only up the Hudson River valley but were also planted in the lower Delaware and Connecticut river valleys where they competed with Swedish and Puritan settlements, respectively. Although the Puritans succeeded in squeezing the Dutch from their Connecticut settlements, their 1643 attempt to found a settlement in the Delaware valley failed. The Dutch finally absorbed New Sweden in 1655.

The Iroquois

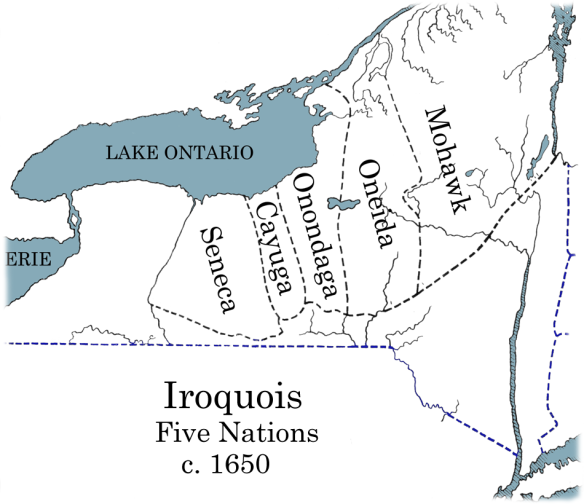

In 1608, Samuel de Champlain sailed up the St. Lawrence with three ships and established a trading post at Quebec. Only eight of his 28 men survived that first winter. Reinforcements the following spring saved Quebec from extinction. As important to the French outpost’s survival was the mysterious vanishing of the Iroquois who had inhabited the St. Lawrence valley from Stadacona (Quebec) to Hochelaga (Montreal), and had so stymied Cartier. Their fate remains unknown. Most likely disease devastated them, and the remnants fled Algonquian and Huron attacks to take refuge among the Iroquois of New York. Despite their retreat, the Iroquois continued to contest the region, sending war parties against the confederation among the Montagnais at Tadoussac and the Huron and Algonquian tribes north of the upper St. Lawrence and Lake Ontario.

To promote his tiny colony’s trade and safety, Champlain joined the anti- Iroquois alliance. Confident of Quebec’s security, in the summer of 1609 Champlain traveled by canoe with three French and 60 Huron and Montagnais warriors up the St. Lawrence and Richelieu rivers and into Lake Champlain. On July 30, they met a war party of 200 Mohawk from the Iroquois tribe near the later site of Fort Frederic. The French remained behind a line of their allies. With arrows notched in their bows, the Mohawk advanced. Neither side fired its arrows. When the Mohawk got within 30 yards, the Huron and Montagnais parted to reveal Champlain and the other French pointing their arquebus. The Mohawk must have stood astonished and fearful-they had never before seen a firearm or a European. The French fired, killing three Mohawk chiefs and scattering the rest. Champlain’s small victory solidified French friendship with the St. Lawrence valley tribes. But those and subsequent killings fired an animosity that would rage through a series of bloody wars between the French and the Iroquois for the rest of that century.

In 1615, the Huron invited Champlain to journey to their homeland in western Ontario. There Champlain, Recollect Father Joseph Le Caron, and several other French visited palisaded villages of the Huron confederation’s four tribes, as well as nearby Ottawa and Neutral tribes, and learned of distant tribes scattered around the Great Lakes basin. The Huron convinced Champlain to join another war party against the Iroquois. This one was a disaster. The Iroquois repelled a Huron assault on one of their palisades and wounded Champlain, thus shattering the spell of French superiority set seven years earlier.

Fort Orange’s establishment in the heart of New York would shift the regional tribal power balance. Until then neither the Five Nation Iroquois nor Four Nation Huron confederacies could prevail in their perennial struggle to defeat the other. The Iroquois recognized that if they could get Dutch guns the balance would tip in their favor. But before the Iroquois could defeat the Huron, they had to dominate the Dutch trade. In 1624, the Iroquois agreed to a truce with the French and Huron in order to defeat the Mahican, who controlled the lands surrounding the upper Hudson valley and Fort Orange. In 1628, the Mahican fled into the Lake Champlain region, abandoning their land to the eastern-most Iroquois tribe, the Mohawk. To Fort Orange, the Iroquois carried an ever greater amount of furs; between 1628 and 1633 alone, the number of skins brought to Fort Orange rose from 10,000 to 30,000.

The tranquility of those colonies lasted until 1675 when Indian wars again tore apart both New England and Virginia. In 1675, the Narragansett had recovered enough from their defeat three decades earlier to re-challenge English rule. That year they withdrew to an island in the Great Swamp, began raiding English settlements, and called on other tribes to join them. Unable to penetrate that flooded, jungle-like maze, the English had to delay retaliation until those waters froze over. In December, Governor Josias Winslow led a 1,150-man expedition against the Narragansett, including 517 militia from Massachusetts, 315 from Connecticut, 158 from Plymouth, and 150 Pequot and Mohegan. Those men finally overran the camp, slaughtering 97 warriors and between 300 and 1,000 women and children, while suffering 70 dead and 150 wounded. The survivors fled to join King Philip (Metacom) and the Mahican. Philip retaliated with raids that devastated the English colonies, killing hundreds of settlers. Later that year, New York Governor Edmund Andros forged an alliance with the Mohawk and got them to attack Metacom’s village that winter and raid the Algonquians throughout the following year. The war sputtered to a close as Philip’s Indians ran out of gunpowder and Philip himself was hunted down and killed in August 1676. No Indian war in American history was more destructive than King Philip’s war-over 3,000 Indians and 1,000 colonists died in the fighting.

Meanwhile, in Virginia a dispute over a hog between a farmer and the Doeg tribe led to former’s murder. Fearing retaliation, the Doeg fled. The Virginia militia pursued them into Maryland where they attacked a friendly Susquehannock village in July 1675. The unprovoked attack sparked a war in which over 300 colonists and hundreds of Indians would eventually die. A civil war then broke out within the Susquehannock war. Virginia’s leaders split over whether to seek peace or continue war with the Indians, with Governor Berkeley heading the peace faction and Francis Bacon the war faction. When Berkeley had Bacon removed from the council for warring against the Indians, Bacon led a rebellion against the governor. Berkeley’s troops crushed Bacon’s Rebellion by January 1676 and the Indians later that year. Under the Treaty of Middle Plantation, the Indian survivors ceded most of Virginia to the English and agreed to settle on reservations.

These two wars dramatically shifted the power balance among Indian tribes, particularly in New England. The Algonqians’ defeat allowed the Mohawk’s resurgence, thus posing yet another threat to the English colonies. In 1680, Governor Andros tried to create a counterweight to the Mo- hawk by inviting the remnants of the defeated Algonquians of New England along with the Mahican and western Abenaki to settle at Schaghticoke 20 miles northeast of Albany. Andros also encouraged the Susquehannock survivors to journey north to settle in the Susquehanna River where they be- came known as Conestogas; others outright joined the Iroquois.

While various civil and international wars engulfed England and its col- onies, New France struggled to survive decades of war with the Iroquois. After regaining New France in 1632, Versailles redoubled its efforts to strengthen it. Trois-Rivieres was founded in 1634 and Montreal in 1642. In 1632, Cardinal Richelieu expelled the Recollets from New France, thus allowing the Jesuits to dominate. New religious orders arrived, including the Ursulines and Soeurs Hospitalieres in 1639 and Company of the Holy Sacrament in 1642. More seigneuries were granted to encourage more settlers. The fur trade was opened to all in 1645.

The European demand for furs rapidly depleted the supply and provoked wars among the tribes. Having wiped out their own fur-bearing animals, the Iroquois stole pelts from others. In 1635, the Iroquois once again began raiding the French and their Indian allies along the St. Lawrence valley. At first, the Iroquois merely attacked convoys of fur-laden Huron canoes paddling down the Great Lakes toward New France. In the 1640s, these raids gave way to a series of “Beaver Wars” against first surrounding and then ever more distant tribes. The Iroquois objective in these wars was to destroy their rivals and capture their fur-rich lands. Hundreds of Dutch muskets gave them the means to do so. Year by year, village by village, Iroquois war parties burned enemy fields and homes, killed hundreds, and herded the survivors back to their own longhouses. The Iroquois virtually exterminated the Huron by 1649, the Petun by 1650, the Neutrals by 1651, the Erie by 1657, and the Susquehannock by 1660. The remnants of those tribes fled either to French missions along the St. Lawrence or to tribes further west; the Susquehannock headed south to Maryland and Virginia. Many of the Iroquian-speaking Huron and other tribes eventually formed a new tribe called the Wyandot, whose villages dotted Lake Erie’s southwestern shore. Not every war ended in an Iroquois victory; a war against the Abenaki in the 1660s ended in stalemate. During these decades, the Iroquois also raided French settlements and killed French missionaries such as fathers Joques in 1642, Bressani in 1644, and Brebeuf and Lalemant in 1649. In all, 153 French died and 144 were captured between 1608 and 1666. Small- pox meanwhile accomplished what their enemies had failed to do-plagues in 1634 and 1661 ravaged the Five Nations. The furs looted from these wars swelled Fort Orange’s warehouses, to New France’s loss; in 1656 the number of furs reaching Fort Orange peaked at 46,000.

The war drastically changed both the Iroquois and New France. The adoption of hundreds of captives transformed Iroquois society. Mission Indians brought with them Christianity and pro-French sentiments. However well they were treated by the Iroquois, adoptees were not inclined to raid their former nations. Captives brought with them their tribal stories, beliefs, crafts, languages, and rituals that at once enriched and diluted traditional Iroquois culture. New France would soon exploit these Iroquois weaknesses.

In Paris, Minister Jean-Baptiste Colbert determined to transform New France into a self-sufficient, diversified colony that filled rather than drained Versailles’ treasury. In 1663, Colbert revoked the private company’s charter and imposed direct royal rule over New France. The first objective was to stabilize the colony’s security by sending it French troops. In 1664, a company from each of four regiments, the Poitou, Orleans, Lalliter, and Cham- belle regiments, arrived in Quebec. Those troops were reinforced the following year with 20 companies from the Carignan-Salieres regiment, creating a combined force of 1,200 regulars commanded by Lieutenant General Alexandre de Prouville. Curiously, those troops were the first French units ever to wear uniforms-brown coats lined with grey or white. 30 In 1665, Colbert sent two energetic leaders to New France, Governor Daniel de Remy de Courcelle and Intendant Jean Talon. In 1668, Colbert ordered Talon to have each parish organize its able-bodied men into militia companies. The intendant would appoint each company’s captain, who was often a retired regular officer or soldier. New France’s population now totaled 3,035, of which one-third were regular soldiers while nearly all other men were in the militia. The much more reliable flintlock musket replaced the slow-firing arquebus. In addition, the French built three forts to guard the north end of Lake Champlain and the Richelieu River valley to wall off the St. Lawrence valley from Iroquois raiders. Colbert also invested royal funds into lumberyards, shipyards, and tarworks, and offered more seigneuries to encourage settlement. New France’s population rose to 10,977 by 1685. Wheat production not only kept pace with the new mouths to feed, but most years actually rose to a surplus that could be exported to France.

With these measures, the military power balance shifted from the Iroquois to the French. The mere threat of a French invasion was enough to induce peace from most of the Iroquois. Exhausted from their own endless wars and a series of smallpox epidemics, by 1665 four of the Iroquois tribes accepted peace-only the Mohawk kept to the warpath. Courcelle was determined to crush the recalcitrant Mohawk. In January 1666, he led 600 French troops down the Lake Champlain and Hudson rivers in a hellish struggle to reach and attack Mohawk villages. En route, 300 died of exposure and the survivors sought shelter in Schenectady. Another 100 died as they trudged home. In October 1666, eager to overcome the previous winter’s disaster, Courcelle mustered 1,300 men, including 600 regulars, 600 civilian volunteers, and 100 Huron and Algonquians, and led them toward the Mohawk villages. Although the Mohawk slipped away before Courcelle’s men, the French burned four villages and destroyed their food stores. Those Mohawk who survived the winter sued for peace the following year. In 1667, the French and Five Nations signed a treaty ending war between them and opening the latter to missionaries and traders.