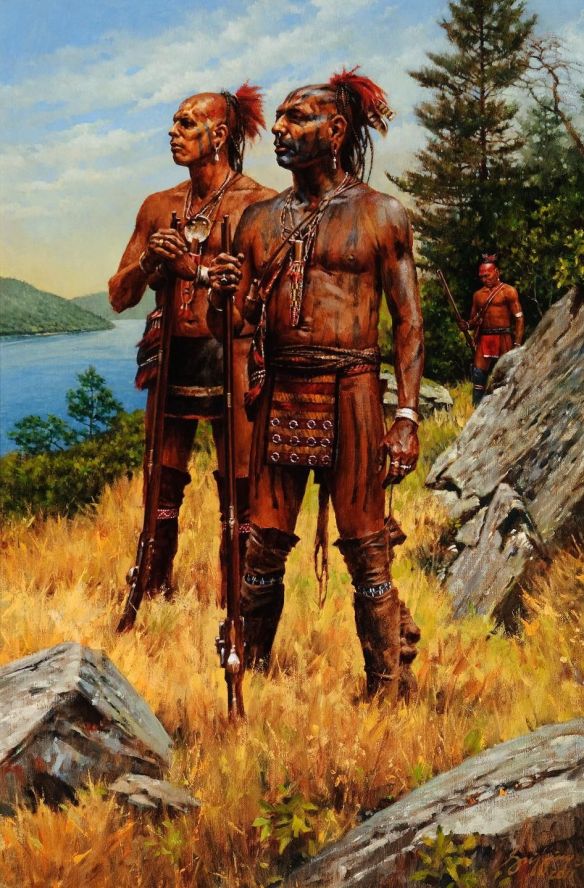

Land of the Iroquois By Robert Griffing

New France sealed the peace by dispatching priests to the Five Nations. There they found a ready audience among the hundreds of former mission Indians who had been dragged as captives to Iroquoia, as well as scores of converts among the native born. Each tribe split among neutral, pro-English, and pro-French factions whose differences over time grew ever wider and more bitter. Increasing numbers of converts migrated to one of three missions near Montreal-La Prairie, La Montagne, or Caughnawaga (Kahnawake), Cataraqui up the St. Lawrence near Lake Ontario, or the predominantly Huron mission of La Lorette near Quebec. Among the Mohawk migrants to Caughnawaga was Kateri Tekawitha, whom Rome later beatified for miracles attributed to her. Iroquois also occupied the lands north of Lake Ontario from which they had earlier driven the Huron and others during the Beaver Wars.

The French also used this peace with the Iroquois to push far up the Great Lakes and buy furs directly from those distant tribes. In 1670, Jacque Marquette founded Fort Michilimackinac at the strait between Lake Huron and Lake Michigan. In 1672, Intendant Talon dispatched Louis Jolliet to find and explore the Mississippi River. Jolliet joined with Marquette and together they paddled down the Mississippi as far as the Arkansas River before heading back. By 1674, Jolliet was in Quebec urging the government to establish trading posts down the Mississippi valley. While intrigued, Talon replied that the St. Lawrence valley’s population had to grow in numbers and prosperity before they could consider colonizing more distant lands. The French also began asserting power over nearby Lake Ontario, a region previously dominated by the Iroquois. In 1671, Courcelle led 50 men up the St. Lawrence to broker a peace between the Iroquois and western tribes. Two years later, in 1673, Governor Frontenac built upon Courcelle’s limited success by leading 400 troops up the St. Lawrence and into Lake Ontario to found Fort Cataraqui (Fort Frontenac) on the northeastern shore. In 1676, the French established a trading post at the Niagara River on Lake Ontario’s southwestern shore. With these two posts, the French captured much of the furs leading down from Lake Erie. Weakened by decades of war, the Iroquois could merely howl in protest.

The French trading posts became magnets for tribes throughout their surrounding regions. The Illinois confederation of a dozen affiliated bands numbered roughly 10,500 people. Increasing numbers of Illinois migrated eastward to the trading posts or to rivers that flowed down to them. This migration into lands recently claimed by the Iroquois prompted war. During the late 1670s and throughout the 1680s, Iroquois war parties ranged as far west as the Mississippi River, yet they failed to exterminate the Illinois confederacy as they had so many other tribes. A 1684 Seneca attack on Fort St. Louis was repulsed by Chevalier Henri de Baugy, 24 French, and 22 Indians. The defeat of the once seemingly invincible Iroquois proved to be the war’s psychological and military turning point. In all, distance, unfamiliarity with the terrain, and enemy numbers ultimately defeated the Iroquois. The wars drove the Illinois into greater dependence on the French, not just for guns but also for advisors and troops.

The initiative passed to the French and their Indian allies. After abortive attempts by Governor Joseph Antoine le Febrve de La Barre to invade the Iroquois lands in 1684 and 1685, in 1687 his successor Jacque-Rene de Brisay de Denonville marched into the Seneca country at the head of 832 troops, 1,030 militia, and 300 Indians. Although his troops never succeeded in catching the Seneca, they did destroy several villages. The Iroquois retaliated with attacks on Fort Niagara, Fort Frontenac, and down the St. Lawrence. Weakened by both the Iroquois raids and a smallpox epidemic that killed 10 percent of New France’s 11,000 settlers, Denonville negotiated a peace treaty with the Five Nations.

During the 1680s, the nonaggression pact of the Iroquois “League” became the alliance of the Iroquois “Confederation.” The French and English alike had long treated the Five Nations as if they were one. Annual meetings at the Onondaga Council fire shifted from maintaining peace among the Five Nations to waging war and diplomacy against others. Nonetheless, there would never be a time in the confederation’s history when more than three of the Five and later Six Nations simultaneously took the warpath. In fact, the council did all it could to keep peace within an increasingly divided confederation.

In 1689, King William’s War (War of the Augsburg Succession) broke out between England and France, and soon engulfed much of Europe. William III declared war on France when Louis XIV tried to conquer the English king’s native Holland and supported a Catholic Stuart claimant to the English throne. In North America, the warfare quickly assumed the characteristics that would continue through four successive wars. 33 With their armies bogged down in Europe, neither France nor England could commit significant forces to North America. London dispatched a mere four infantry companies to New York and another to Newfoundland. Versailles sent only warships to convoy its annual supply fleet to Quebec. With each war, France and England would boost the number of troops they committed to the New World. But the colonists were mostly forced to decide North America’s fate on their own.

Colonial troops and their Indian allies waged war through raids and occasional major campaigns. Over the next few years, the French led war parties of Abenaki against New Hampshire and attacks composed of various tribes to the Hudson and Mohawk valleys. These raids burned Fort Casco, Fort Loyal, Salmon Falls, Schenectady, and York. In response, the English helped finance Iroquois raids along the St. Lawrence valley. An Iroquois raid in July 1689 burned the town of Lachine, a mere seven miles from Montreal. In 1690, an English raiding party voyaged up the Lake Champlain corridor to destroy La Prairie before escaping a French and Indian pursuit. That same year, William Phips led 736 men to capture Port Royal in Nova Scotia.

Raids bloodied the frontier for an- other half dozen years. The governors of New France and some New England colonies offered bounties for scalps. The Iroquois suffered a humiliating defeat in 1696 when Governor Frontenac led 2,000 French and Indians to the Onondaga heartland, whose villages and crops he destroyed.

The Treaty of Ryswick abruptly ended King William’s War in 1697. The French agreed to recognize William III as England’s legitimate king, along with English claims to Newfoundland and Hudson Bay. Peace in Europe, however, did not extend to North America. The Abenaki continued to war against New England while the Iroquois ravaged the St. Lawrence valley. Several French expeditions along with separate Ottawa and Objibwa war parties attacked the Five Nations. Half of the Iroquois’ warriors died in these wars. In 1701, the Iroquois could do nothing to prevent the French from building Fort Detroit to solidify their control over the upper Great Lakes’ fur trade. Instead, that same year they meekly accepted a summons by Governor Frontenac to join representatives of 30 tribes at a Montreal council which agreed to a “Great Peace” among them all. That same year, the Iroquois signed a peace treaty with the English at Albany. In both treaties, the Iroquois promised to remain neutral in any war between France and England.

Ironically, while peace finally settled along the northern frontier, war again engulfed Europe, sparked by the death of the childless Spanish king Carlos II. Louis XIV tried to impose his grandson on the Spanish throne and thus extend French control over Spain’s Italian and Flemish territory. Other great powers supported other claimants. In 1702, England officially entered what became known as Queen Anne’s War or the War of the Spanish Succession. Queen Anne and her government hoped not just to contain Louis XIV’s latest aggression but to use the war to seize Spain’s Caribbean sugar islands and annual treasure fleet.

During the war, the periodic raids that had all along terrorized the north- east frontier increased in number and ferocity. Abenaki attacked the cities of Casco, Wells, Winter Harbor, York, and Deerfield, slaughtering hundreds of settlers and dragging hundreds of others into captivity. Caughnawaga Iroquois raided Schenectady. Iroquois raids burned and looted along the St. Lawrence valley. Western Indians attacked the Iroquois. Bounties were once again offered for enemy scalps and prisoners. Privateers captured hundreds of enemy merchant ships.

Under the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht ending Queen Anne’s War, Versailles ceded English claims to Newfoundland, Hudson Bay, Acadia except for Isle Royale (Cape Breton), and Isle Saint-Jean (Prince Edward Island); recognized English sovereignty over the Iroquois; and permitted the English to trade in French territory. France’s ally, Spain, lost nothing in North America, but did have to grant England the strongholds of Gibraltar and Minorca in the Mediterranean. England reaped huge benefits from the war, along with greater defense commitments.

The Utrecht Treaty is a classic example of a peace accord that sowed the seeds of future conflicts. The failure to delineate these territorial trades and fulfill other tenets unleashed a half century of conflicting claims that only war could resolve. Most controversial of all was Article 15, which seemed to allow for free trade among all the tribes and asserted British sovereignty over the Iroquois. Did free trade permit Englishmen to peddle their goods at the gates of French trading posts? If not, just where were the territories of the Iroquois and other tribes drawn? The English and French proclaimed the Iroquois as British subjects; the Iroquois rejected that distinction.

From 1727 rival trading posts at Oswego [English] and Niagara [French] made “the Six Nations’ economic dependence on European trade . . . complete, and the profits flowed almost entirely in one direction.” This was, of course, the same pattern of dependence and exploitation that had been and would be repeated across North America. That dependence caused the Iroquois to insist that those two forts remain free from attack should another war break out between France and England.

In 1740, the Emperor Charles VI died without a male heir. Over the next few years, most of Europe’s powers joined this War for the Austrian Succession. In October 1743, the Bourbon kings of Spain and France signed the Treaty of Fontainbleau, reviving their old Family Compact. The British and French fought on the continent and oceans for at least a year before Versailles formally issued a war declaration in March 1744.

In North America the struggle was known as King George’s War. In New York, the rivalry between the French and British for an Iroquois alliance bitterly split the Longhouse. Officially, only the Mohawk fought with the British; the other tribes remained neutral. But the pressure tore each tribe into near warring factions. Many Mohawk drifted north to Caughnawaga near Montreal. Other disgruntled Iroquois migrated to the upper Ohio River valley where they became known as Mingo. Onondaga and Cayuga along with Iroquois from the other tribes flocked to the Oswegatchie mission until, by 1751, over 3,000 Iroquois had settled there. During the final French and Indian War, Oswegatchie and Caughnawaga became bases for war parties against New York, New England, and even their former kinsmen.

The English failure to forge a solid alliance with the Ohio tribes followed a similar reverse earlier that summer at a council with the Iroquois. On June 16, 1753, Mohawk Chief Hendrick stood, locked eyes with Governor Clin- ton, and proclaimed: “Brother when we came here to relate our Grievances about our Lands, we expected to have something done for us. . . . Nothing shall be done for us. . . . [A]s soon as we come home we will send up a belt of Wampum to our Brothers the 5 Nations to acquaint them the Covenant is broken between you and us. So brother you are not to expect to hear of me any more, and Brother we desire to hear no more of you.”

New York’s defense all but collapsed with the words of King Hendrick. The Mohawk had been the only Iroquois tribe that had consistently sup- ported the British. Their villages were only several score miles from Albany and had consistently acted as a buffer against war parties of French and Indians from other tribes, including those of the Six Nations. Their entreat- ies on behalf of the British at Onondaga had frequently blunted the calls of others for war against the colonies. Now, if war broke out, the Mohawk would not only allow French and Indian war parties through their land, they might well join them. Hendrick’s statement also destroyed the British claim to the Ohio River valley by dint of their suzerainty over the Iroquois. The Iroquois rejection of neutrality on top of the French expedition to the upper Ohio would lead to the Albany Conference of 1754.

On September 18, 1753, the Board sent orders to the governors of New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Massachusetts, Virginia, New Jersey, Mary- land, and New Hampshire to send delegates to a grand council with the Iroquois. Its orders to the governors declared: “His Majesty having been pleased to order a Sum of Money to be issued for Presents to the Six Nations of Indians, and to direct his Governor of New York to hold an Interview with them for delivering these Presents, for burying the Hatchet, and for renewing the Covenant Chain with them, We think it our duty to acquaint you therewith.” After the necessary exchanges of letters, a date for the Albany assembly was set for June 14, 1754. Governor Clinton was given the duty of inviting and hosting the delegates.

Indian Warfare

The nature of warfare changed dramatically after the Europeans arrived. Until then, warfare was ritualized as lines of warriors wearing reed-armor approached each other and exchanged barrages of insults and arrows. Few died in the exchanges. European diseases devastated tribes, thus creating unprecedented needs to fill the places of vacant loved ones with captives and scalps. Trade competition provoked devastating wars over hunting and trapping grounds and trade routes. European weapons gave the Indians unprecedented power to destroy their enemies. Warfare became ever more savage with the enemy’s annihilation the goal. French and English bounties for scalps made killing enemies as desirable as taking captives. Some practices continued. Scalping was universally practiced long before and after the Europeans arrived, as were, for many tribes including the Iroquois, variations of both ritual and subsistence cannibalism. When a village decided to send warriors to the French or British the chief would give the ally a bundle of red- dyed sticks to show how many warriors had been committed to the war.

To varying degrees, warfare was an integral part of each tribe’s culture. Blood feuds or “mourning wars” provoked most bloodshed. Indians did not endure the deaths of loved ones and neighbors stoically, but immersed themselves in long periods of mourning that could involve self-neglect, laceration, or even mutilation, and attacks on other tribes. When someone died, his or her place and name had to be filled by bringing captives or scalps back from the warpath. Indians sublimated grief and avenged deaths through war, which usually stimulated more grief and the need for vengeance when warriors failed to return or the raid provoked deadly enemy counterattacks. Clans rather than villages initially tended to go to war, but dragged in the entire tribe as enemies retaliated. Thus were tribes trapped in a vicious, never-ending war cycle.