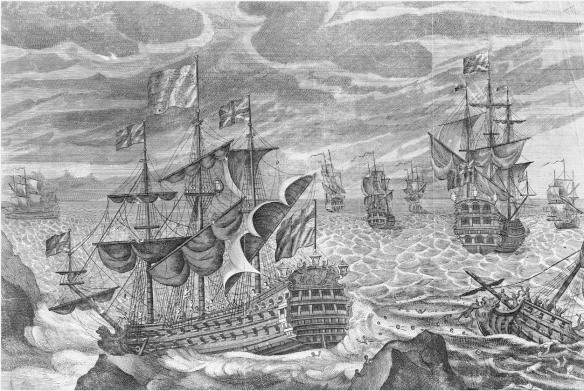

In October 1707, Association, commanded by Captain Edmund Loades and with Admiral Shovell on board, was returning from the Mediterranean after the Toulon campaign. She was lost in 1707 by grounding on the Isles of Scilly in the greatest maritime disaster of the age.

This was a highly successful combined operation against Toulon with the total elimination of France’s Mediterranean fleet thanks to an Anglo-Dutch naval bombardment which was combined with a siege by Austrian and Piedmontese forces. The siege was stopped when it appeared clear that the city would not fall speedily and, instead, could resist until the arrival of overwhelming French forces. During the siege, the Anglo-Dutch fleet played a key role in supporting the siege, providing cannon, supplies and medical care. The Toulon campaign indicated both the growing importance of amphibious operations and the extent to which the key issue was not the seizure of territory, but the achievement of particular strategic goals in the shape of destroying the fleet.

In 1707 the Duke of Marlborough during the War of the Spanish Succession, proposed an assault from north and south. In the north he could depend on Belgian bases, but in the south Toulon had to be seized and made into a depot for an advance up the Rhone. There were delays before the Emperor could be coerced into any operation. Eugene advanced along the Provençal coast aided by Shovell’s fleet. The land operations against Toulon failed (July-Aug. 1707) but Shovell destroyed the naval base with the French fleet in it. The threat was enough to bring the French back from Germany and Spain, but the failure was an expensive strategic defeat.

Marlborough’s year of victory was followed by a year of disappointment. Louis XIV tried to open peace negotiations, but the triumphant Allies were having none of it, unless the French abandoned all dynastic claims to Spain. During 1706 the Imperialists had won a victory at Turin, which effectively cleared the French from much of Northern Italy. Plans were laid to build on this success in 1707 by staging an invasion of Provence, supported by an Anglo-Dutch fleet. Prince Eugene was sent to Italy to lead the offensive, and consequently Marlborough was starved of the German troops he needed to campaign effectively in Flanders. In the end Eugene advanced as far as Toulon, where a combination of disease and French reinforcements caused him to lift the siege and withdraw to Italy.

Toulon in 1707 was a well-fortified town with a modern earth wall with 7 bastions. They were well-armed with cannons from disarmed ships of Toulon squadron. There were two gates, one (St. Lazare) between Minims & St. Bernard bastions, & the other (New) between Royal & Arsenal bastions.

Toulon fortifications (see above):

A – Mimins bastion

B – St. Bernard bastion

C – St. Ursule bastion

D – De la Fonderie (Foundry) bastion

E – Royal bastion

F – Arsenal bastion

G – Du Marais a Gauche

H – batteries at New Dock

I – batteries at Old Dock

J – Ponche-Rimade bastion

K – earth redoubt at Minims bastion

L – entrenched field camp

The War at Sea, 1701-1714

Opposing navies had resumed their familiar game on the high seas as soon as war broke out. The French resumed the guerre de course their Navy had practiced during the second half of the Nine Years’ War, prosecuting it to great effect. The privateers of Dunkirk alone brought in nearly 1,000 Allied or neutral prizes. The French effort was so effective Parliament passed the “Cruisers and Convoys Act” in 1708, specifically assigning additional warship escorts to convoy duty along the Western Approaches and off major British ports. This forced French cruisers and privateers to hunt in the West Indies, off the coast of Africa, and in other less well-defended waters. The Allies also practiced cruiser warfare and privateering against French convoys and individual merchantman. This forced the French to use some warships to escort Spanish convoys across the Atlantic and led to squadron-on-squadron fighting in the Caribbean in August 1702. Unlike the French, who cleaved to a strategy of guerre de course throughout the war, the Allies also sought to utilize their clear advantage in battlefleets to outflank the French operationally and strategically. The Allies suffered early failures at sea, however, notably their inability to take Cadiz through amphibious assault during August-September 1702. The troops were put ashore too far from the city, the officers were inept and lost control, and most of the expedition got drunk and began looting and desecrating Catholic churches (perhaps consciously recalling the tradition of Francis Drake). On the return journey, English escorts surprised the Spanish silver fleet and their French escorts at Vigo Bay (October 12/23, 1702). The Allies missed most of the silver, but captured or destroyed 12 rated French warships and 19 Spanish vessels. The outcome of the fight and the prospect of more amphibious assaults into Iberia helped persuade Portugal to switch to the Grand Alliance. The next year, England formally detached Portugal from its French alliance, signed the Methuen Treaties, and secured at Lisbon a base of operations for the Royal Navy in the Mediterranean.

An Anglo-Dutch amphibious operation failed to take Barcelona in June 1704. On its return journey, it took Gibraltar instead. That led to the only fleet action of the war, off Velez-Malaga (August 13/24, 1704). Although the French won a tactical victory, operationally the battle blocked them from retaking Gibraltar, thereby inflicting a major wound. Afterward, the French Navy and privateers cleaved to an effective and lucrative guerre de course: in the last decade of the war, the French took over 4,500 Allied prizes on the high seas, and sank or burned hundreds more Allied or neutral ships. French squadrons, usually under War of the Spanish Succession private loan if not privateer command, also raided and extorted various overseas outposts from West Africa to the Caribbean (and later, against Rio de Janeiro in 1711). An English squadron attacked a Spanish treasure fleet in the West Indies in 1708, intercepting or sinking the equivalent of £15 million of bullion.

Meanwhile, the Allies moved troops by sea into the Mediterranean from the north, as dominance at sea enabled them to sustain armies fighting in Spain. In 1704 an Anglo-Dutch fleet escorted 8,000 Redcoats and 4,000 Dutch to Spain, where they joined 30,000 Portuguese fighting Philip V ostensibly for the Grand Alliance. An Anglo-Dutch fleet parked off Barcelona for two years after an amphibious operation finally captured that city on September 28/October 9, 1705. The French Mediterranean squadron and fortified city of Toulon was bombarded, burned, and besieged from July 28-August 22, 1707. The French sank or burned 15 of their ships-of-the-line at anchor rather than see them captured or burned by Allied bombardment. However, the blockade had the principal effect of provoking an even large French commitment in Iberia. By 1708 Parliament authorized, and the Royal Navy transported, 29,395 men to campaign in Spain. That did not prevent a decisive defeat of the British at Almanza in April 1707. Sardinia fell to Allied marines in August, providing a potential naval base in the western Mediterranean close to France. Minorca was taken shortly thereafter, along with its superb harbor at Mahon. Once the Allied naval blockade of Barcelona was lifted at British behest, the end came into sight for Archduke Charles in Spain. Among the last significant actions involving sea power was a failed British expedition to take Québec mounted in 1711. It was a poorly planned disaster.

SHOVELL, Sir Cloudesley or Clowdisley (1650-1707), seaman, cut out the corsairs at Tripoli (1676) and cruised against the Barbary pirates until 1686. He was Rear Admiral in the Irish Sea in 1690 and 2-in-C at Barfleur (1692), where he broke the French line. He was C-in-C in the Channel in 1686-7, became M. P. for Rochester from 1698 and was Comptroller of Victualling as well as C-in-C in the Channel from 1699 to 1704 when, with Rooke, he captured Gibraltar and fought the B. of Malaga. Next he co-operated with Peterborough at Barcelona (1705) and with the Austrians and Savoyards before Toulon (1707), where he destroyed the French Mediterranean Fleet. His brilliant career ended abruptly in a shipwreck on the Scillies when he reached the beach exhausted and a woman murdered him for his ring.