Marines detachment of Major Caesar Kunikov, shortly before the night of February 4, 1943, when they took part in the landing operation and seized a bridgehead south of Novorossiysk, known as “Malaya Zemlya”.

Although Soviet attempts for a second huge encirclement had been thwarted, the German position in the southern sector was still perilous, and the eyes of the Soviet command turned to the isolated Seventeenth Army. Plans for a Soviet amphibious landing in the Novorossiysk area had first been drawn up in November 1942, and at a Stavka meeting on 24 January 1943, a combined amphibious and ground operation to encircle the German Seventeenth Army was proposed. On land, the Soviet 18th and 46th Armies would seize the Kuban River crossings in the Krasnodar region and then push west towards the Taman Peninsula while the 47th Army would launch a direct attack on Novorossiysk. Meanwhile, the amphibious landing would place forces into the rear of the German defences and move to link up with 47th Army. The combined operation would encircle Seventeenth Army and prevent it from withdrawing into the defensible Kuban Bridgehead. At this meeting, the forces in the area were also reorganised.

Transcaucasus Front’s Northern Group, under the command of General Ivan Maslennikov, was renamed North Caucasus Front, and the remainder of Ivan Tyulenev’s Transcaucasus Front returned to its original role of guarding the southern frontiers with Iran and Turkey.

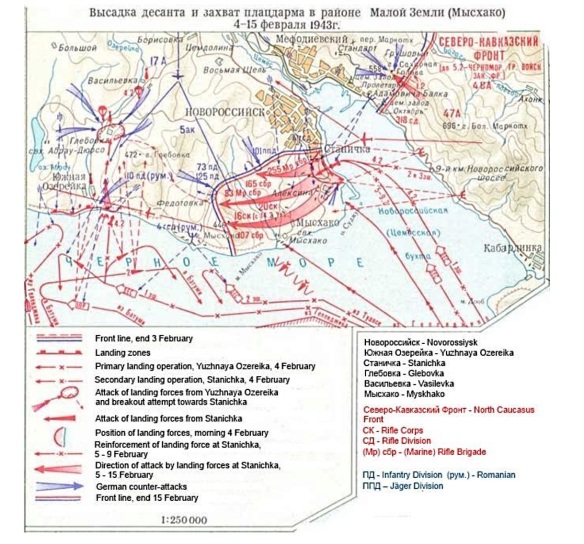

The location chosen for the landing operation was Yuzhnaya Ozereika, about thirty kilometres southwest of Novorossiysk, and the detailed plan was drawn up by ViceAdmiral Filipp Sergeyevich Oktyabrskiy, the commander of the Black Sea Fleet, and timed for 01:30 on 4 February. The timetable was as follows:

00:45: A parachute force of eighty men would be dropped at Glebovka and Vasilevka, to the north of Yuzhnaya Ozereika, and bombing raids would be carried out on German defensive positions around the landing zones.

01:00: A naval bombardment would be launched by a Black Sea Fleet fire-support squadron commanded by Rear-Admiral Lev Anatolevich Vladimirskiy and comprising the cruisers Krasniy Kavkaz and Krasniy Krym, the destroyer leader Kharkov and the destroyers Besposhchadniy and Soobrazitelniy.

01:30: The main landing at Yuzhnaya Ozereika, commanded by Rear-Admiral Nikolai Yefremovich Basistiy, would be launched, along with a simultaneous diversionary landing at Stanichka in the southern suburbs of Novorossiysk. Dummy landing operations would also be feigned at a number of locations along the southern coast of the Taman Peninsula: Anapa, Blagoveschenskiy, the Sukko River Valley and Cape Zhelezniy Rog.

The main landing force comprised two echelons. The first was formed up in Gelendzhik and was made up of 255th Independent Red Banner Naval Infantry Brigade, 563rd Independent Tank Brigade and a separate machine-gun battalion. The second echelon formed up in Tuapse and comprised 83rd Independent Red Banner Naval Infantry Brigade, 165th Infantry Brigade and 29th Anti-tank Artillery Regiment. Both groupings underwent intensive training in landing operations throughout January.

Even during the earliest preparations for the operation, however, a number of officers expressed doubts over the selection of Yuzhnaya Ozereika as the site of the main landing, citing the unpredictable winter weather and sea conditions, the presence of numerous minefields in the area and the distance from the ultimate objective of Novorossiysk.

The operation ran into serious problems from the start. On 27 January, 47th Army began its offensive in the Verkhnebakanskaya and Krymskaya areas, but was unable to force a breakthrough at any point. Although the original plan stipulated that the landing operation would not begin until such a penetration had been achieved, the

Transcaucasus Front command nevertheless gave the order for the landing to proceed, partly in the hope that it would divert German forces and help 47th Army to achieve its aim.

The first landing group was late setting out from Gelendzhik and made slower than expected progress in heavy seas, so Basistiy sent a request to Vladimirskiy on Krasniy Kavkaz and to Oktyabrskiy, requesting a 90-minute postponement. Without waiting for confirmation from Oktyabrskiy, Vladimirskiy ordered his ships to hold fire and Basistiy postponed the arrival of the dummy landing operations did not receive this information and acted according to their original orders.

Oktyabrskiy, however, did not wish to delay the operation as doing so would deprive him of the cover of darkness. He ordered that the original plan should be adhered to, but this message did not reach Basistiy and Vladimirskiy until it was too late for them to revert to the original plan. Again, Oktyabrskiy did not communicate with the air-support, parachute and dummy landing groups, so they remained oblivious to the unfolding chaos.

The bombing raids and bombardment of the dummy landing sites were launched in accordance with the original timetable, as was the parachute drop, but one of the transport planes was unable to locate the drop zone and returned to base, reducing the strength of the parachute force by over 25 percent before the operation started. This disconnect between the different parts of the operation alerted the defending German and Romanian forces, allowing them to ascertain that a landing operation was imminent and also its likely location. At 00:35, V Corps placed all its forces defending the southern coast of the Taman Peninsula on the highest alert.

At 02:30, the naval support ships began their 30-minute bombardment against the German and Romanian defences at Yuzhnaya Ozereika. The fire was poorly-directed, however, and although over 2,000 shells were fired, the gun emplacements and defensive positions were largely undamaged. At 03:00, the cruisers ceased firing and set course for port, although the destroyers continued firing. The landing craft of the first group approached the shore at around 03:30, but came under intense fire and suffered heavy losses. Many of the tanks in the first landing group were released too far from the shore so their engines flooded and they were immobilised in the surf.

A group of 1,427 men, with 10 tanks, was able to reach the shore. They quickly captured Yuzhnaya Ozereika and set out for Glebovka, a few miles to the north, but without support, they could not maintain the advance. The bulk of the group, including the last two remaining tanks, was pushed back and isolated in an area about one kilometre west of Yuzhnaya Ozereika on the morning of 5 February. Over the next few days, small groups tried to force their way through to Stanichka, and about 150 succeeded. Another group of 25, along with 18 paratroopers and 27 partisans, reached the coast to the east of Yuzhnaya Ozereika and were picked up by a motor boat on the evening of 9 February. Another 542 men of the landing group were captured. On 6 February, Seventeenth Army reported that the landing force at Yuzhnaya Ozereika had essentially been destroyed, and the following day, reported that 300 enemy dead and 31 U.S.-built tanks lay on the beach.

The diversionary landing at Stanichka, in contrast, proceeded virtually exactly as planned. At 01:30, torpedo boats raised a smoke screen across the shore, and fire from support vessels and from batteries on the eastern coast of Tsemess Bay were much more successful in silencing German guns than had been the case at Yuzhnaya Ozereika. The first landing groups, under the command of Major Tsesar L. Kunikov, disembarked and were able to seize a beachhead. At 02:40, Kunikov signalled for the second and third echelons to be landed. The landing party seized several buildings on the southern edge of Stanichka and was able to hold the beachhead until it was further reinforced. The bridgehead quickly became known as “Malaya Zemlya” (The Small Land).

The success against the Yuzhnaya Ozereika landing appears to have led to a degree of complacency among the German command regarding the Stanichka operation. At 00:15 on 6 February, General Ruoff sent a message of congratulations to all the commanding officers who had been involved in the defence against the two landings, and later in the day, V Corps’ war diary reported that the landing force at Stanichka was encircled and that its attempts to expand its beachhead would be defeated. A German offensive to throw the landing party back into the sea was planned, but was not scheduled to start until 7 February, when parts of 198th Infantry Division were due to arrive from Krasnodar to reinforce V Corps’ line in a number of locations around Novorossiysk. Ivan Y. Petrov, the commander of the Black Sea Group of North Caucasus Front, displayed no such hesitation and quickly decided to divert all of the forces that had been intended for the main landing to reinforce the success of the Stanichka diversion.

Within a few days, over 17,000 men, twenty-one guns, seventy-four mortars, eighty-six machine guns and 440 tons of supplies had been landed on the beachhead. Kunikov was fatally wounded by a shell splinter on the night of 11–12 March and was posthumously awarded the title Hero of the Soviet Union. He is buried in Heroes’ Square, close to the waterfront in the centre of Novorossiysk.

The debacle at Yuzhnaya Ozereika has been largely overlooked in the Soviet history of the war, as attention focussed on the Malaya Zemlya landings. The official History of the Great Patriotic War describes the events at Yuzhnaya Ozereika in just two sentences while devoting several pages to the success of the auxiliary operation. During this period, Leonid Brezhnev was serving as a political officer with 18th Army, and he made a number of trips by boat to Malaya Zemlya to encourage the troops. During his term as general secretary of the Communist Party (1964-82), the legend of Malaya Zemlya was taken to new heights. In 1973, Novorossiysk was awarded the title of Hero City, elevating it to the status of the likes of Stalingrad and Leningrad in terms of its importance in the war. A series of massive memorial complexes were constructed, including one at the site of the Malaya Zemlya landings.

The question of what the Malaya Zemlya landing actually achieved, beyond its propaganda value and tying down German forces, is worthy of further consideration. Grechko claims that the operation created favourable conditions for the liberation of Novorossiysk, but this view is difficult to support, as the city was not recaptured until a full seven months after the landing operation and after the Germans had already decided to withdraw the whole of Seventeenth Army from the Kuban Bridgehead.

Several writers, including Tieke, note that the presence of the Soviet forces at Malaya Zemlya prevented the Germans from using the port facilities at Novorossiysk. This argument is also questionable. There were already significant Red Army forces on the high ground on the eastern side of Tsemess Bay, where the front line had been static since September 1942. These forces provided artillery support for the landing operation, so they would also have been able to threaten any German vessels attempting to enter or exit the port. In any case, the German-held ports and airfields farther to the rear were sufficient for Seventeenth Army’s supply needs. During March, for example, the supply and evacuation totals by sea and air were as follows:

To further supplement the supply system, a cable-car system across the Kerch Strait, with a capacity of 1,000 tons per day, went into operation in June.

A second question that warrants further examination is that of what could have been achieved if the main landing at Yuzhnaya Ozereika had unfolded as planned. The landing forces at Malaya Zemlya were concentrated on a relatively narrow peninsula, so the opposing German defensive line remained quite short. Nevertheless, the quickly reinforced Soviet force put severe pressure on the German defences and created concern at Seventeenth Army headquarters. On 7 February, the army’s war diary reported that it had been fully pushed onto the defensive by the reinforced enemy, and on 21 February, it stated that the decrease in the combat strength of its forces in the Novorossiysk area was “particularly serious.”

The defences along the coast around Yuzhnaya Ozereika were weaker than at Stanichka, and the fact that the small landing party was able to force its way inland as far as Glebovka suggests that if it had been reinforced to a level approaching that at Stanichka, it could have represented a serious threat to the entire left wing of Seventeenth Army’s defensive line. Ultimately, the failures of the Yuzhnaya Ozereika landing and 47th Army’s offensive in the centre of Seventeenth Army’s line allowed the latter to hold a continuous defensive line through the spring and summer.