In December 1941, the Imperial Japanese Navy was the world’s third largest. It may have been the best. It certainly had the best naval air arm.

Of its 1,500 pilots, nearly all had 600 or more hours of flying time, half of it in the combat aircraft they were flying. Most of the formation leaders had as much as 1,500 hours. The majority were veterans of combat over China, where the Naval Air Service had flown strategic bombing, close support, and air cover missions since the “China Incident” began in 1937.

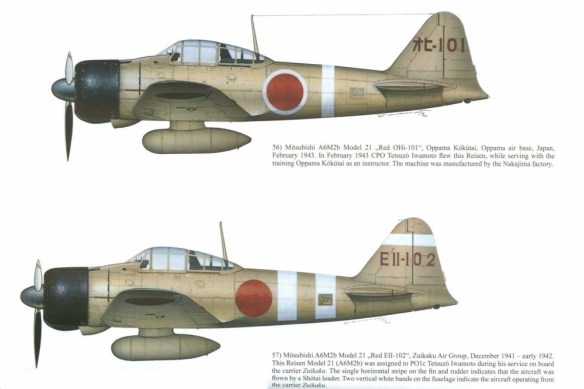

Their aircraft were fully worthy of their pilots. The A6M Zero was the best carrier-based fighter in the world. The B5N Kate was equally adept at torpedo bombing and level bombing. The D3A Val was at least as good as the notorious German Stuka. The land based G3M Sally and the G4M Betty had long range and were good high-altitude bombers and excellent torpedo bombers. The Japanese rounded out their strength with several types of seaplanes and the H6K Mavis, a four-engined flying boat with incredible range. All of this was supported by a strong corps of some of the most expert mechanics in Japan.

The carrier-based planes, nearly five hundred strong, flew from nine modern carriers, including some of the best in the world. That was not only three times as many as the United States Pacific Fleet had, but more than the whole United States Navy’s carrier strength.

But by the summer of 1945, the Naval Air Service’s planes (too many the same early-war types) squatted under camouflage net ting and in caves, waiting for their mechanics to prepare them for semitrained pilots to take one last flight, crash-diving into a ship of the American invasion fleet-if they got that far. How the mighty had fallen.

But why?

The Japanese Naval Air Service died from the same cause as so much of the Japanese war effort-faulty grand strategy and a weak economic base. To be brief about the second, Japan had to import practically every essential item of a modern war economy except coal. And in 1944 alone, a fully mobilized American air craft industry produced almost as many planes (better ones, too) as Japan produced during the whole period of 1942-45.

The Japanese strategic stumble is less well known. Basically, they planned on a short war leading to a decisive battle that would put the enemy in a position that he would not have the political will to fight his way out of.

This strategy meant hitting by surprise, fast, hard, and often. Specifically, it meant preparing a defensive barrier stretching from the Kuriles in the north in a great crescent down to the anchorage of Truk in the Caroline Islands far to the south. Planes, destroyers, and submarines from these bases would hack away at the American fleet (what other one need Japan fear?) until it approached the Home Islands. Then the Combined Fleet would sortie at full strength and so thoroughly crush American offensive capabilities in the Pacific that the United States would seek a negotiated peace.

The concept of a short war has been attributed to the Samurai mentality; to the code of bushido, emphasizing daring and aggression; and to stark realism. The Japanese had not forgotten how narrowly they escaped running out of men and money at the end of the war with Russia, even after winning the decisive battle at Tsushima.

So their main naval striking force, the aviators, were polished to perfection for a short war. The force had once been composed exclusively of graduates of Eta Jima, the Japanese naval academy, survivors of a four-year curriculum that made Annapolis look like a prep school. In 1929 suitable enlisted men were admitted to the two-year flight training course, which washed out about 80 percent of the candidates. Then in 1931 potential pilots were allowed straight in from civilian life.

Having a larger pilot pool helped somewhat, but it also introduced the hierarchical Japanese class system into naval aviation. Physical punishment was allowed; initiative usually was not. This environment was not calculated to produce the best mind-set among the new lower-class pilots.

The planes they climbed into also had a few limitations. None of them had armor or self-sealing fuel tanks. Radios were in short supply, and so heavy and prone to static interference from unshielded ignitions that some pilots refused to carry them. And of course parachutes were bulky and implied an unthinkable willingness to be taken prisoner, and therefore were refused. They could have saved many pilots’ lives.

So the Japanese Naval Air Service flew off to an initial victory that slowly turned into doom.

They earned their first triumphs. Pearl Harbor was an attack on a scale that no other navy in the world could have executed until well into 1943. And while survivors were still getting first aid, off in the Philippines air strikes from Formosa (now Taiwan) were devastating American airpower in the islands.

General Douglas MacArthur helped the Japanese cause by failing to disperse his planes despite knowing the war had started. The Japanese fighter pilots who escorted the bombers were flying at extreme range, their fuel-air mixtures leaned out as far as they could go without stalling.

These were apparently amazing feats-but there was a scribble of handwriting on the wall at Wake Island. There, four Marine F4F Wildcats proved their toughness by taking to the air full of holes and not only shot down Japanese planes but damaged a light cruiser and sank a destroyer.

The Japanese went on running wild from Burma to the fringes of Australia. But they were losing as many as two hundred planes a month (army and navy) to operational accidents (read: piling up on a runway hacked out of scrub, ankle-deep in mud, and with a few rocks left for good measure). And pilots who died nosing-over in a pothole were just as dead as those killed dropping a bomb on an Allied warship.

The Indian Ocean saw a lot of that kind of bombing in April, when the Japanese carriers went east. The Japanese carriers also saw what a really determined defense could do-over Ceylon they lost forty to fifty planes.

Worse was to follow. Later in the spring the Japanese divided their carriers, sending two south to cover an attack on New Guinea and getting the rest ready. Warned by the code-breakers, the Americans stop-punched them in the Coral Sea, although losing one fleet carrier against one Japanese light carrier. The real blow to the Japanese was that one of their carriers had her flight deck wrecked and the other lost most of her air group-another dent in the supply of experienced Japanese naval pilots.

So both carriers missed Midway, where they might have turned the tide. As it was, the Japanese lost four carriers-giving them a shortage of first-class flight decks, from which they never really recovered. Many pilots survived, but hundreds of the veteran mechanics were not so lucky-and that was another irreparable blow.

The Battle of Midway also let one other plum drop into American hands. In the Aleutians, a Japanese diversionary raid left a flyable Zero upside down on an uninhabited island. Salvaging it, the Americans got it back in the air and tested it thoroughly. It did not influence the design of the F6F Hellcat (already flying when the Zero crashed), but it did allow the U. S. Navy to learn its opponent’s weakness and use its new fighter more effectively.

The Japanese now turned to an advance down the chain of the Solomon Islands, seeking another approach to cutting off Australia. (The Japanese services never agreed on a plan for invading that continent-but then, they hardly ever agreed on much.) They established an air base on the island of Guadalcanal. The United States promptly landed marines to seize the base. The Japanese counterattacked by air, land, and sea.

Guadalcanal

The Battle of Guadalcanal may have decided the Pacific War. It certainly decided the fate of the Japanese Naval Air Service. Bombing raids from Rabaul and carrier battles at sea took a toll on Japanese planes and pilots. The Japanese lost about seven hundred planes of all kinds, as well as most of their pilots-and many of the lost pilots were the irreplaceable veterans. The United States lost nearly as many planes, but fewer pilots and crewmen, and the U. S. pilot-training program had plenty of three-hundred hour pilots in the pipeline, just waiting for their new planes and carriers. The Japanese, on the other hand, were stretched so thin that to send a veteran pilot back to be a flight instructor would deprive a frontline squadron of an indispensable leader.

Meanwhile, Japanese pilot training hours were dropping below two hundred, few of those in combat aircraft. Most of the new pilots were being either siphoned off into new air groups or thrown straight into the maw of the Solomons campaign.

The Japanese evacuated Guadalcanal in January 1943. That ended Japanese strategic offensives in the Pacific. The rest of the year saw no great fleet clashes, because both sides were building up their strength for the next one.

The United States did a better job, both qualitatively and quantitatively. By the end of the year it could sweep the Gilbert and Marshall islands with strikes from five fleet and six light carriers, which then sailed south to eliminate Truk as a working naval base (along with most of the ships in it and all the planes on its runways).

Rabaul

The elimination of Rabaul as a barrier to the advance on the Philippines also proceeded with reasonable speed. The Japanese surface fleet fought aggressively at night, but the United States ruled sea and sky by day and island-hopped steadily “up the ladder of the Solomons.” In November 1943, it eliminated Rabaul as a fleet base. In the next few months, it effectively eliminated that base’s air power, which included several replacement air groups intended for the carriers of the Combined Fleet. This blockade ended up trapping yet more pilots and mechanics out of the war as effectively as if they had been in POW camps. From the roofs of their bunkers, they could contemplate new and superior American aircraft such as the P-38 and F4U Corsair swatting the last Zeroes out of the sky.

This did not improve a Japanese situation that was going from bad to worse. Mitsuo Fuchida, who had led the attack on Pearl Harbor, joined the staff of a land-based naval air group intended to defend the Marianas. He was appalled to discover that the group had fewer than two hundred planes and that the average training time for the new pilots was 120 hours-not enough time logged to let them even fly some of the new planes that were at last reaching the front safely, let alone use them in combat. The mechanics were in equally short supply and equally undertrained, likely to be hopeless with the new planes such as P1Y Frances, D4Y Judy, B6N Jill, and the magnificent long-range flying boat, the H8K Emily.

The Japanese needed more than new planes. They needed flight decks, as they had gained only one fleet carrier in the last year, and they needed fuel for both planes and ships. Unfortunately, while the East Indian oil fields were now producing again, American submarines were taking an increasing toll on Japanese tankers. They were also targeting Japanese destroyers, leaving both convoys and carriers with increasingly thin escorts.

Nor would it have helped Japanese morale to discover that the Americans had a complete set of the plans for the defense of the Marianas, correctly assumed to be the next major objective. Filipino guerrillas had retrieved the plans from a Japanese staff officer who’d swum ashore from a crashed plane.

So when the American Fifth Fleet and a multidivision Marine and Army landing force appeared off the Marianas, the Japanese response held few surprises. The Mobile Force sailed out, with new air groups aboard its five large and four small carriers. Meanwhile, the Americans had systematically eliminated all the Japanese aircraft based on the islands, craft which the Japanese had hoped would be an equalizer, and cratered most of the runways that the Japanese carrier planes were supposed to use for shuttle bombing operations.

Then the Fifth Fleet positioned itself west of the Marianas and waited for the enemy to come to it. On June 19, 1944, the Japanese came-four massive carrier raids, all of which were intercepted, three of which were nearly annihilated. The Japanese lost three hundred planes to American interceptors and anti-aircraft fire. The Americans had one battleship lightly damaged.

That same day, American submarines sank two of the best Japanese carriers. On the next day the Americans delivered a counterstroke, launching two hundred planes at extreme range and knowing they’d have to return at night.

They sank another carrier and two tankers, in addition to wiping out the few remaining Japanese planes. Then they headed for home. Many ditched for lack of fuel. Many more might have except that Admiral Marc Mitscher, commanding the fast carries, threw caution to the wind and ordered his ships illuminated. That grand gesture saved many plans and crews, and provoked no attacks.

The Battle of the Philippine Sea has been discussed in such detail because it was the greatest carrier battle of all time-and the death knell for Japanese naval aviation. The last carrier force it sent to sea was a diversionary force at the Battle of Leyte Gulf, four carriers with only 116 planes, and they were all sunk or lost.

Then Japan’s naval pilots flew into the shadowy land of the kamikazes, where they played an effective role. Certainly many of them must have gone in the same spirit as other pilots who thought that Japan was doomed: life in a defeated Japan would not be worth living, so why not go out doing as much damage to the enemy as possible?

May Americans never have to answer such questions. And may we try not to judge too harshly those who have.