In 1939 and 1940 the aircraft industry produced more than 10,000 aircraft per year, while a December 1940 plan called for 16,000 in 1941. During the first half of that year 3,900 aeroplanes rolled out of the plants, and this rose to 11,800 during the remaining six months of 1941. Total engine production that year was 28,700 units, although the Soviet aero-engine industry suffered the perennial problem of developing reliable, high-performance motors. Instead, they usually produced derivatives of imported designs, while the change to new engines meant that production output dropped from 22,686 in 1939 to 21,380 the following year, although it then recovered. However, the engines that powered the wartime generation of Russian-built VVS aircraft were often unreliable, leaked oil and were difficult to maintain.

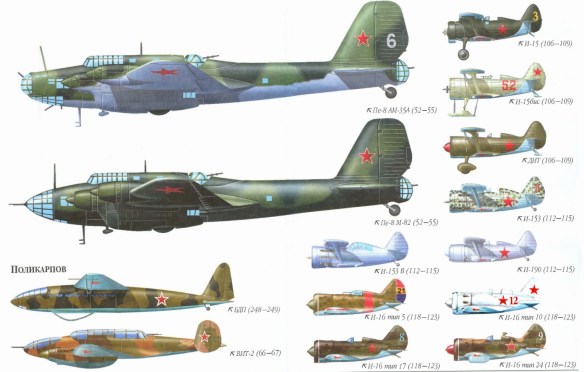

The collective impact of these problems was severe. The Ilyushin DB-3 medium bomber with composite construction of a wooden fuselage and steel wings, and the improved DB-3F (Il-4 from March 1942), began to augment the TB-3 from 1939. However, the new heavy bomber, Petlyakov’s four-engined TB-7 (Pe-8 from January 1942), proved more difficult to produce. Indeed, although its maiden flight took place in December 1936, only a handful were in service by 1941.

Spearheading the re-equipment programme from 1939 was a new generation of fighters – Yak-1, MiG-3 and LaGG-3, together with light bombers such as the twin-engined Yak-2/4 and single-engined Su-2, all of which began to trickle into the regiments from 1940. In their aircraft-design Gulag, Petlyakov and Myasishchev began work on a long range escort fighter, rather like the Bf 110, but in 1940 this was changed at the NKVD’s behest to a long range dive-bomber as the Pe-2.

Many pilots distrusted the new aircraft, and with some reason. The MiG-3 was not only heavy but some had defective synchronisers that meant the nose-mounted machine guns shot off their propellers when fired, the hydraulics of the LaGG-3 were extremely unreliable, the Yak-1 engine proved troublesome and the canopy tended to stick when the aircraft dived.

One field where the VVS was ahead was in ground-attack, or ‘assault’ (Shturmovaya), aviation. Its assault trooper (Shturmovik) pilots provided the Red Army’s spearheads with direct air support by strafing and bombing enemy concentrations. Most of these aircraft were armoured versions of the single-engined Polikarpov R-5 army cooperation biplane, the R-5Sh and R-Z, augmented by I-5 and I-15bis fighters. Experience in Spain had confirmed the need for the dedicated ground-attack aircraft, and Sergei Ilyushin began designing the Il-2, whose pilot and engine were in an armoured compartment with armoured glass windscreen. The aeroplane entered production in 1941, and it would be the backbone of VVS ground-attack units despite the fact it was never a very stable weapons platform.

Unfortunately for the VVS, the re-equipment programme was bungled, for rather than withdraw units to re-equip, the bureaucrats often despatched a quota of new aircraft to regiments. At the Baltic District’s Kovno airfield, for example, two fighter regiments had 253 aircraft, including 128 MiG-3s, while a few bomber regiments on the airfield received the Su-2 and others small numbers of Pe-2s.

Many of the new generation of aircraft would receive affectionate nicknames often based upon their official designations. The Yakovlev fighters were called ‘Yakovs’ (Jacob/Jake/Jim) or ‘Yakis’ (Jakes), the Pe-2 was ‘Peshka’ (Pike) while the single-seat Il-2 would be called ‘Gorbun’ (Hunchback), although throughout the war the Il-2 was commonly called ‘Ilyusha’ and the units that flew them were known as ‘Mudlarks’ (Ilovs), based upon the word for mud (il). Not all the names were complimentary, and the lumbering, wooden LaGG-3 with its unreliable hydraulics was reportedly described as a Guaranteed Lacquered Coffin (Lakirovannyi Garantirovannyi Grob), although some have dismissed this claim, arguing that the Soviet authorities would have regarded it as ‘defeatism’. The new aircraft helped to fuel a further expansion of the VVS, and in February 1941 it was decided to create 106 regiments, including 15 (later 13) equipped with long range bombers. In 1939 regiments were organised into air brigades, but the Winter War showed the need to concentrate air power into larger formations. Each district was reorganised into a number of divisions, with two to five regiments of three to five squadrons, each with 12 aircraft, augmented by a few independent army cooperation squadrons with R-5s. Most divisions were mixed (Smeshannaya), with both fighter and strike (bomber or assault) regiments, and every army had at least one to support its operations. Dedicated fighter and bomber divisions tended to remain under district command, fragmenting VVS strength. Although each army headquarters was supposed to have a VVS commander, few did, and few of them would prove competent.

Their operations, together with those of reserve units, the DBA and PVO, were coordinated in peacetime by District VVS commanders who became Front VVS commanders in wartime. With the disbandment of the AON in the winter of 1939–40, the long range bombers were concentrated into the DBA and organised into bomber divisions (usually of three regiments) and then paired into corps from 5 November 1940. One or two corps were assigned to each Western military district, which, in the event of war, would become a Front (army group). To support the new divisions, work started on reorganising the rear services’ infrastructure, although this was not scheduled for completion until August 1941.

For the Soviet Union, the prospects of war seemed to recede in August 1939 when the USSR and Nazi Germany signed a non-aggression pact that helped Hitler take Poland and allowed Stalin to regain territory lost to nationalists during the Russian Revolution. Stalin sought to buy time for a renaissance of his forces by bribing Germany with substantial quantities of food and raw materials, but he knew that sooner or later the Nazis and Communists would fight.

The pact allowed the Red Army to invade eastern Poland and the Baltic states and deploy up to 250 kilometres west of the original frontier, but this aggravated VVS problems. Each regiment was supposed to have its own airfield, but there were few in the occupied areas. The Russians hastily began an extensive construction programme, which was hampered by two severe winters and the NKVD, who were responsible for its execution. NKVD head Lavrenti Beria would criticise his subordinates on 22 May 1941, for trying to build large numbers of airfields rather than well-equipped air bases. This left most VVS squadrons on little more than cleared fields. Indeed, of 1,100 VVS airfields, only 200 – mostly DBA bases in the rear – had concrete runways, while there were too few satellite airfields to house dispersed regiments.

Within the Western District only 16 of 62 airfields had concrete runways, while none of the 23 scheduled for the Baltic District had been completed. Furthermore, some 30 ‘airfields’ were actually airstrips designed as satellites to the main bases. On 10 April 1941, Moscow approved plans for another 251 airfields, mostly in the West, but work had not begun by the time the Germans attacked. With space at a premium, 14 airfields held two or three regiments. Most of the available airfields were too close to the German border. The situation was most acute north of the Pripet Marshes, where the Russians had advanced deeper into Poland but found fewer suitable airfield sites. In the Baltic Military District 39 per cent of the aircraft were concentrated in three airfields, while in the Western District 45 per cent were on six airfields. South of the Pripet Marshes the advance was shorter and sites more plentiful – only 25 per cent of the Kiev District’s aircraft were on four airfields, including 206 at Lvov, while in the small Odessa District 17 per cent of the aircraft were in Odessa itself.

On 27 December 1940, Defence Minister (Commissar) Marshal Semon Timoshenko ordered all airfields within 500 kilometres of the border to be camouflaged by 1 July 1941. Progress was slow, and attempts within the Kiev District during the spring of that year to build revetments for aircraft, vehicles and supplies were hamstrung by labour shortages. Acute shortages also plagued the VVS. The lack of accommodation meant that in the Western District some pilots were billeted five kilometres from their bases, while few airfields had adequate stocks of fuel and ammunition. There were also severe shortages of trained radio operators for the district VVS headquarters, which were often at a third of establishment. This left commanders dependent upon landlines, with fatal consequences in the summer of 1941.

Rychagov faced tremendous challenges in trying to prepare the VVS for future combat – he needed to re-equip his regiments, ensure their crews were adequately trained, provide sufficient supplies for a prolonged campaign and organise an infrastructure that could move those supplies, repair damaged aircraft and bring in replacements. This required a mature individual with broad experience in all aspects of military aviation and the administrative skills to address the prime problems in detail. What Moscow got was a 30-year-old who had peaked in the Winter War as commander of a small air force on a minor Arctic front, who disliked ‘flying a desk’ and preferred to visit the regiments to enjoy the convivial company of fellow airmen. Smushkevich was also no administrator, and being crippled with leg injuries following a crash, he frequently had to work from his bed, which he moved into his office.

The only silver lining was that, unlike the mechanised forces, there were few disputes over doctrine. In a comprehensive review of the Red Army’s Winter War shortcomings, Smushkevich noted, ‘The need to divide the VVS into the Red Army’s air arm to operate with the ground forces and an Operational Level air arm supporting large-scale operations has been proved beyond reasonable doubt.’

Soviet military aviation was divided into four elements – Frontal Aviation Air Force (Voyenno-Vozdushnye Sili-Frontovaya Aviatsiaya, VVS-FA), Naval Fleet Air Force (Voyenno-Vozdushnye Sili- Voyenno-Morskoy Flot, VVS-VMF), Long Range Bomber Aviation (Dahl’niy Bombardirovochnaya Aviatsiya, DBA) to March 1942 then Long Range Aviation (Aviatsiya Dahl’nevo Deystiviya, ADD) and Home Air Defence (Protivovozdushnaya Oborona, PVO). The VVS-FA and VVS-VMF provided support for the Red Army and the Red Navy at the Tactical/ Operational Level (army and army group levels), with operational command delegated to army groups (Fronts) and armies, each with their own air commander. DBA was under the control of the Defence Ministry in peacetime and VVS headquarters in wartime, and was to conduct Operational/ Strategic Level missions (army group and the rear) with formations assigned to front commands, as were many fighter regiments of the PVO.

While it recognised the value of defending, and attacking, industrial and administrative centres, the Red Army leadership had no truck with Italian General Giulio Douhet’s claims that strategic bombing alone could win a war. Indeed, the Russians would use the term ‘attacks upon administrative, political and military sites in the hinterland’.

The VVS’s army support mission would be reflected throughout the Great Patriotic War against Germany and her allies. From the beginning to the end of this conflict, nearly two-thirds of VVS sorties (63.44 per cent) were at the Tactical Level either supporting the troops in the forward edge of the battle area (FEBA) or shielding them from air attack, while 5.52 per cent were spent striking Operational Level (operations for commands up to army group/ front headquarters) targets. Another 14.62 per cent of sorties were escort missions, while 11.18 per cent were reconnaissance. DBA would also be diverted to Tactical Level air support, which accounted for 40.44 per cent of its sorties, while 45.80 per cent were Operational or Strategic Level attacks. Before the war VVS doctrine anticipated destroying enemy air power in the air and on the ground, while the PVO covered the assembly of reserves for a counter-offensive in which Soviet airmen would pound enemy communications to ease the way for the armoured formations.

The Red Army leadership could see for itself the potent power demonstrated by combining mechanised forces with air power, and during 1940 there was growing disquiet about the ability of the VVS. Confusion about organisation and the execution of operations became all too clear in December 1940, at the moment when Hitler published his directive for the invasion of the Soviet Union. During the summer of that year, following the successful German campaigns in the West, Timoshenko summoned senior officers to the Defence Ministry for a conference on the Red Army’s status. Afterwards, five reports were presented looking at the latest ideas in warfare, including one by Rychagov on ‘Combat aviation in the offensive and the struggle for air superiority.’ This sparked a bitter argument over the best way to achieve air superiority. The Baltic and Kiev District VVS commanders, General-leitenantii Gregorii Kravchenko and Yevgenii Ptukhin, said their experience fighting the Japanese at Khalkin-Gol and the German– Italian forces in Spain showed this goal was best achieved in the air. Rychagov straddled the fence and advocated the destruction of the enemy both in the air and on the ground, but he produced no concrete plans to achieve this goal.

From 8 January 1941, watched intently by Leningrad Party boss Andrei Zhdanov as Stalin’s representative, the senior commanders conducted war games involving German invasions, firstly in the Western (Belorussia and eastern Poland) District and then the Kiev District. The Red Army was judged to be successful in its defence of these areas, although the exercises had a considerable degree of unreality. Yet Zhdanov was sceptical, and when the war games concluded, Stalin summoned the participants to the Kremlin on 13 January to discuss the results. He was not pleased by the explanations and demanded realistic discussions among the commanders, which led the VVS officers to complain bitterly about their structure and training.

While these complaints were largely dismissed, the Communist Party’s Central Committee decided on 25 February to introduce the aviation division instead of the smaller aviation brigade, and Rychagov apparently implemented this on 10 April. Of more immediate effect was Stalin’s appointment of Georgii Zhukov as Army Chief-of-Staff on 14 January. Although he was an advocate of air power, having been a grateful customer at Khalkin-Gol, his pursuit of excellence began a process which, ironically, almost destroyed the VVS.

The war games confirmed the Soviet General Staff’s belief that the main enemy thrust would be towards the Baltic states and Belorussia, but Stalin was convinced the Germans would go for the Ukraine’s mineral and agricultural riches. Consequently, the defence plan was a compromise, with the largest concentration in the Kiev and Odessa Districts, while retaining substantial forces in the Baltic and Western Districts. Naturally, VVS dispositions in 1941 reflected this, although General-maior Aleksandr Novikov had some 1,000 aircraft, plus 227 PVO fighters, to shield Leningrad from the Finns.

Kravchenko had been sent to the General Staff Academy and replaced in the Baltic District by General-maior Aleksei Ionov, who had another 1,200 aircraft, while in the Western District, General-maior Ivan Kopets had 1,500 aircraft. The largest concentration – more than 1,900 aircraft, and 114 PVO fighters – was under Ptukhin, augmented by more than 800 aircraft plus 72 PVO fighters in the Odessa District under General-maior Fyodor Michugin.

These figures exclude some 180 reserve aircraft, but on 1 June 1941, only 1,597 (19.4 per cent) were new generation aircraft. Some 768 of these were in the southern districts, the latter also receiving most of the 600 modern aircraft delivered to the military districts in the following weeks. Nevertheless, by 22 June only 27 per cent of combat aircraft were modern, with 690 aircraft awaiting delivery from the factories. Most of the DBA’s 1,300 aircraft were modern DB-3s but, with the exception of nine TB-7s, the 212 heavy bombers were obsolete.8 The VVS reconnaissance force was similar in size to the Luftwaffe’s, but many of its 270 long range aircraft lacked cameras – an essential sensor found in all Fernaufklärungstaffeln aeroplanes.

Because Soviet industry (like its counterpart in Germany) was more interested in producing aircraft than spares, the number of serviceable aeroplanes declined. On 1 June 1941, 12.9 per cent of VVS and DBA aircraft in the West were officially unserviceable (that figure was nearly 24 per cent in the DBA). This total may in fact be an underestimate, although it compares favourably with the Luftwaffe, where the figure was 26 per cent. However, the Russian numbers may relate only to aircraft undergoing overhauls or major repairs, for it is worth noting that on 15 June, 29 per cent of all tanks were being overhauled while 44 per cent were unserviceable with lesser problems.

In addition to air forces supporting the armies, the Navy also had small forces supporting each fleet. The strongest naval air concentration was the Baltic Sea Air Force (Voyenno-Vozdushnye Sily Baltiyskogo Flota, VVS-KBF) with 656 aircraft (including 353 fighters and 172 bombers), closely followed by the Black Sea Air Force (Voyenno-Vozdushnyye Sily Chernomorskogo Flota, VVS-ChF) with 624 (including 346 fighters and 138 bombers). The NKVD also had a small air force in the West, with 12 squadrons (150 aircraft) of mostly reconnaissance aircraft, but with some SB bombers and two squadrons of MBR-2 flying boats.