On 7 November, he told the cabinet that despite the turmoil inside Germany, there was no military reason for Germany to surrender. Their Army was retreating in reasonably good order, it was holding a continuous front, and with winter approaching, there was no reason why they should not be able to establish a solid defensive line. There was still time for the RAF to inflict the coup de grâce. The War Cabinet officially approved the Air Ministry plan to transfer as many bombers as possible from the Middle East to Bohemia to attack industrial and ‘moral targets’, but the Foreign Office stopped short of sanctioning a raid on the capital.

On 6 November, a delegation had been dispatched from Berlin with instructions to obtain a ceasefire at any price. On 8 November, they met Foch and were told the price was total surrender. The Germans requested an immediate temporary armistice while they considered the French demands; Foch refused and gave them three days to decide. A raid on Berlin by one plane might appear a mere gesture, but politically Balfour decided that it could send a very strong and direct message to Germany’s leaders. Clearance was given for the RAF to bomb Berlin. The Handley Page V/1500 was to set off on 9 November and the Vimy in France was to follow as soon as it was ready. Poor weather forced the first V/1500 raid to be postponed for forty-eight hours. At dawn on 11 November, the crews prepared for another attempt, but before they could get into the air, news arrived that an armistice would come into effect later that day. There would be no opportunity to bomb Berlin—not in this war at least.

For the Air Ministry, it was an anti-climax and unsatisfactory conclusion to their strategic bombing campaign—the end of the war had come before the value of the strategic bomber could be proven. Indeed, far from being proven, doubts were growing about it having any significant military value. The optimism of mid-summer had been replaced by a growing realisation that little physical damage was being inflicted on the German economy. The ability of the bomber to cripple German industry had been vastly exaggerated. The effect of the bombing on the German population had also been overestimated. Deaths as a result of any one raid rarely reached double figures and less than 1,000 German civilians died in bombing raids during the First World War. Tragic as each individual loss was, given the huge problems Germany faced and the horrendous scale of casualties at the front, the impact of bombing casualties on the population as a whole was slight. The deaths through air bombardment were dwarfed by the 400,000 German civilians who died in 1918 as a result of the flu pandemic.

The deprivations caused by the blockade, the onset of the flu pandemic, the surrender of Germany’s allies and the general hopelessness of the military situation were far more significant factors in the decline of German morale. The scattering of a few bombs over Berlin in the last hours of the war might have added to the sense of hopelessness. Alternatively, the indignation such attacks caused might equally have helped unite a broken nation and stiffen resolve. Most likely of all, it would scarcely have been noticed in a country already racked by despair, disorder and internal dispute.

The war had ended with no evidence that a country could be intimidated into accepting defeat by the air weapon. Haig had apparently been proven right. The bombing of London, or any other city, could not change the course of the war. It was perhaps easier for Haig in France to make this judgement than the politicians and military sitting in London as the bombs fell around them. Haig’s insistence that the Army should get priority over home air defence might seem cold and calculating, even callous, but he simply did not believe the compatriots of his stoic conscript Army would cave in so tamely under the threat of air attack. It is neither difficult nor surprising to find evidence that civilians find bombing extremely distressing, but it is hard to find evidence that it induces a desire to surrender. As well as causing grief, the killing and maiming of innocent civilians inspires resentment and anger. It does not take much, if any, manipulation by the government and media to exploit these emotions to stiffen the determination of a nation to fight on. As Mond had suggested in 1909, ‘No nation would make peace because the enemy was killing its civilians’.

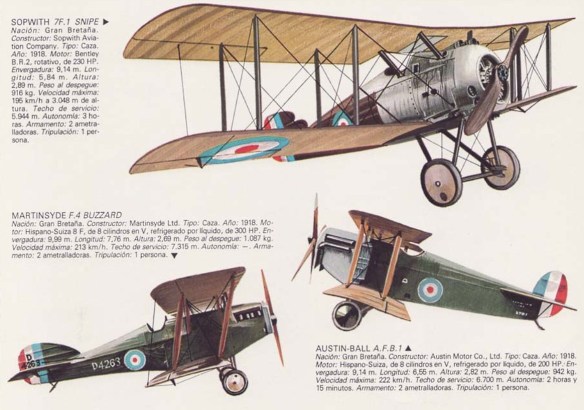

As a last resort, advocates of long-range bombing claimed that even if the bombers did not achieve decisive results, the effort that the enemy had been compelled to put into air defence was a victory for the bomber. The problem was that long-range bombers required far more resources to build and operate than the short-range interceptors that shot them down: ten Snipes could be built for the price of one Handley Page V/1500. Fighters were also more versatile than huge long-range bombers. Interceptors were often the same machines as those operating over the front, but huge and cumbersome Handley Page V/1500 bombers would be as vulnerable as Zeppelins over the battlefield.

Perhaps the biggest error made by the pro-bombing lobby was that bombing was easy and preventing it difficult. By the end of the war it was becoming clear the opposite was far closer to the truth. The defences of both sides were improving quicker than the efficiency of the bomber forces. Even if the defences were overcome and targets found, planners were becoming aware of the countermeasures open to the country under attack. Cities could not be moved but industries could. As a last resort, dispersion and relocation of vulnerable industries was always possible. Tiverton’s greatest fear had always been that a premature and unsuccessful offensive against any particular target would give the enemy time to relocate to a more distant part of Germany.

The German daylight raids on London had provoked a radical shift in British air policy. At the time, it seemed like the dawn of a new era in warfare, but even before the war ended a little more than a year later, there was growing evidence that this had been a massive over-reaction and misjudgement. Long-range bombing was fraught with far more problems than anyone had appreciated and the battle for resources in the last year of war demonstrated that Britain did not have the means to build a long-range bomber fleet and maintain an effective Army and Navy. By November 1918, it was the advocates of strategic bombing who were very much on the back foot, desperate to find last-minute proof, or even just a little evidence, that they might still be right.

Only the politicians seemed to have been won over. Many seemed to have been taken in by some of the extraordinary claims made for the destructive capabilities of very small numbers of bombers. As always, it was the politicians who tended to be most impressed by the morale argument. This is scarcely surprising; it is, after all, the politicians’ responsibility to worry about civilian morale. Defending one’s own civilians from aerial bombardment is a perfectly reasonable priority for any government. The ability to retaliate effectively made politicians feel more confident about securing the support of their own people and less vulnerable to threats from enemies. The political advantages and the military benefits of having an intimidating long-range bomber force would become increasingly muddled in the years ahead.

While the strategic use of air power had failed to make the expected impact, the tactical applications of air power had gone from strength to strength. Aerial reconnaissance and artillery direction developed very rapidly, achieving a degree of operational sophistication and efficiency that, even after four years of war, the long-range bombing advocates could not come close to matching. The problem of the air and artillery combination was that it worked so well: it stifled movement on the battlefield and deepened the stalemate. However, as the war progressed and new tactics began to break the tactical gridlock, air power was able to demonstrate its versatility.

In any sort of conflict, reconnaissance is crucial. If reconnaissance had been the only task aircraft were capable of performing in 1918, it would still have justified the resources poured into the development of military aviation; however, aircraft were capable of much more. Attacking ground targets began to produce significant results once it was appreciated that the more relevant they were to the immediate battle, the more difference they could make. By the end of the war, fighter-bombers were being employed and directed in exactly the same way as artillery. Ground attack was merely an extension of the artillery support an Army corps could expect. By 1918, close air support was not an innovation, it was normal. The expectation was that eventually even a platoon commander held up by an enemy strongpoint should be able to call for air support. Techniques for supporting ground forces more normally associated with the Second World War had become established procedures in the First World War.

In defence, close air support had demonstrated its mobility and ability to deal with emergencies. In attack, it had in extreme circumstances demonstrated the ability to turn retreat into a rout. Most of the time, its impact was far less spectacular. It was just another useful tool available to Army commanders, but this capability alone was valuable enough to justify its existence and should have been enough to guarantee its future.

In 1918, the Army was developing along the right lines. The War Office was developing high-speed tanks that could do more than just crush barbed wire and support the infantry. Armoured close support planes and self-propelled artillery were being developed, which could support deep thrusts into the enemy rear. No longer would the infantry have to wait for the artillery to move into place before advancing. The fast moving tanks still had to be developed and the tactics they would use formulated, but the air element was already in place. Britain had its blitzkrieg air force.

As valuable as the fighter-bomber had proven, the Army appreciated the first duty of the fighter was to establish air superiority. The struggle for air superiority was a battle that proved as crucial as any fought on land or sea. To win it required the right training, tactics, organisation and equipment. In the autumn of 1918, the Germans might have been losing the war, but with their excellent Fokker D.VII and ‘Flying Circuses’, they were ahead of the RAF in most of these respects.

No country could have been quicker than Britain to see the need for an efficient fighter, but developing the correct solution proved to be a very slow process. False analogies with naval warfare had led to an obsession with aerial battleships that could dominate huge areas of airspace. The realities of war eventually forced an acceptance that speed and agility were the key qualities, more important even than firepower. No other item of First World War military equipment had such a rapid turnover as the fighter. A new design might only dominate the skies for months before becoming obsolete. No item of military equipment was considered more important. The Fokker D.VII was considered such a vital element of the German war machine, it was the only item of military equipment specifically mentioned by name in the list of war material the Germans had to hand over as the price for an armistice.

The flying qualities required of an air superiority fighter are simple to list: ease of control; ability to turn tightly and change direction quickly; high horizontal, climbing and diving speeds; high acceleration; and high service ceiling. The problem is that many of these qualities are contradictory and one can only be achieved at the expense of another. The first Martinsyde F.3/4 fighters to reach the RAF would have found themselves opposed by the Fokker D.VIII. No two fighters could be more different than the light Fokker and the powerful Martinsyde. Each had its advantages and it would have been an interesting contest between the two.

Developing the correct fighter tactics had been a particularly hard struggle for the RFC and RAF, but theories about providing indirect protection by dominating the enemy rear had eventually given way to more focused fighter operations in the battle zone. Fighters had to operate where they were likely to encounter the enemy, not where theories dictated the battle ought to take place. If patrols flying low over the battle area needed higher level patrols to protect them, then an independent battle for air superiority between the opposing fighter forces might well emerge, but fighter resources could not be wasted looking for a battle that served no purpose. The first priority was to establish superiority in the immediate vicinity of friendly forces, whether they are troops in the front line or reconnaissance and bombing machines penetrating enemy airspace. Once this has been established, then it might well be profitable for fighters to patrol further afield. Trenchard’s offensive patrols would have been an excellent way of extending and reinforcing air superiority already achieved over the battlefield, but they were not a way of achieving that air superiority.

Ironically, given that much air force strategy was based on naval practice, the Navy and RAF ended up making the same mistakes and having to learn the same lessons. The Navy began the war believing a broad offensive policy aimed at dominating the oceans would enable individual vessels to move freely. The policy had failed and been replaced by the more pragmatic approach of concentrating shipping in convoys that were protected by strong naval escorts. Exactly the same had happened in the air.

It was the expansion of the strategic bomber force, not the tactical air force, which was in most doubt when the war came to an end. If the war had continued into 1919, the RAF, with a large Army in the field to support, would undoubtedly have continued to develop as a powerful tactical force. The development of a powerful strategic bombing force would have been far more problematic. Britain did not have the resources to build a strategic and a tactical air force. If the war had continued, the huge expense of the strategic bomber, in terms of manpower and resources, and the needs of the Army and Navy, would probably have continued to restrict the development of the Air Ministry’s independent bombing ambitions.

Much had happened in four years. In 1914, the British had committed a small professional Army supported by four RFC squadrons to a European conflict that was expected to be of limited duration. Instead, the war had lasted for more than four years and a huge conscript Army had been raised. Plans for the spring of 1919 envisaged fifty divisions of the British Army supported by a tactical air force with 400 day and night bombers, 400 low-level fighter-bombers, 300 two-seater fighter-reconnaissance planes and 700 armoured corps planes, all protected by 1,200 single-seater fighters. In 1919, the British soldier would not have lacked air support. It was a level of support that British soldiers fighting future battles in future wars would be denied. Why they did not get it is another story.