Field Artillery

The mission of the field artillery was to support the infantry. The objective was also to bring a superior number of guns into action at the decisive place and time. In German doctrine the priority of fire was directed against the targets that were most dangerous to the infantry. At the beginning of an engagement, priority of fire was normally given to counter-battery fire, to cover the infantry approach march. The intent was to gain fire superiority over the enemy artillery. During the infantry firefight, priority of fire was generally given to fire on the enemy infantry, but counter-battery fire would continue to be conducted. Given the increased use of the terrain for cover and concealment by all arms, targets for the artillery would often be fleeting and there would not be enough time to eliminate the target entirely.

The French Model 97 75mm gun was the first to incorporate a recoil brake. Since the gun was now stable, the gun aimer and loader could remain seated on the gun, which allowed an armoured shield to be added protect the gun crew. The new French gun could fire up to twenty rounds a minute, against eight or nine for the German Feldkanone 96, which had just been introduced. Given this increased firepower, the size of the battery could be reduced from six guns to four. The French also introduced the armoured caisson. The 75mm caused a sensation and the French imagined it to be practically a war-winning weapon. French tactics prescribed that the 75mm would provide the firepower necessary to support the infantry attack with rafales, intense bursts of fire, to shake the enemy infantry. This was area fire, which made up in volume what it lacked in accuracy.

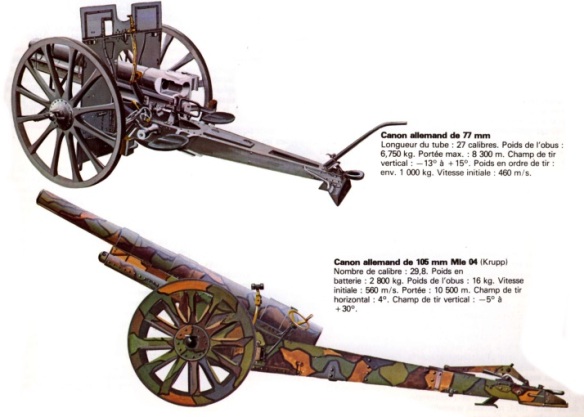

German divisional field artillery consisted of two weapons: a 7.7cm flat-trajectory gun (Feldkanone 96 n/A) and a 10.5cm high-trajectory light howitzer (leichte Feldhaubitze 98/09). The maximum effective range of the 7.7cm gun is a subject of some controversy; there were frequent complaints that the French 75mm considerably outranged the German gun. In fact, the theoretical maximum range was rarely relevant. In practice, the maximum effective range was variable, depending on the ability of the battery commander to acquire targets, see the fall of shot and adjust his shells onto the target. The author of the FAR 25 regimental history said that 4,400m was long range, and targets at 5,000ms were out of range, even though the maximum range of the shrapnel fuse for 7.7cm gun was 5,300m, and for the contact fuse 8,100m.

The light howitzer was provided with a recoil brake and the tube could be elevated to a high angle, which allowed it to fire easily from covered positions. The parabolic arc taken by the shell made it very effective against targets behind cover and in field fortifications. The howitzer was a German specialty: the French army did not possess any. Instead, the French developed a shell for the 75mm had fins that gave it a curved line of flight supposed to mimic that of the howitzer shell. This expedient was unsuccessful in combat and the French were to regret the lack of a howitzer.

A wartime-strength German battery included six guns or howitzers, 5 OFF, 188 EM and 139 horses, the battery commander’s observation wagon, two supply wagons, a ration wagon and a wagon for fodder. Each regiment had six batteries divided into two three-battery sections, which were commanded by majors. A field artillery regiment included 36 guns, 58 OFF, 1,334 EM and 1,304 horses, including two light ammunition columns, each with 24 caissons. There were 4 OFF, 188 EM and 196 horses to each ammunition column. Ammunition columns were formed only at wartime and for a few training exercises. The field artillery did not have mobile field kitchens, which was found to be a severe problem in mobile operations. In each active army corps there were three gun and one howitzer regiments: one division had two gun regiments, the second a gun and a howitzer regiment. Reserve divisions had only one gun regiment.

A German field artillery piece was drawn by six horses and consisted of the gun, its limber and a six-man gun crew, and an ammunition caisson, with its own five-man crew. The gun and caisson were provided with armoured shields that protected the crews against small arms fire and shrapnel. The gun could be operated even if 50 per cent of the crew were casualties. Artillery batteries could immediately replace losses in personnel and horses by drawing on the regimental ammunition columns, which took replacements from the divisional ammunition columns and so on.

The gun commander rode on a horse, ‘drivers’ rode on the gun team horses, the gunners rode on the limber or the gun itself. The German field artillery battery of six guns would generally deploy in firing position with 20 paces (about 13m) between guns. The caisson and two of the caisson crew would deploy to the right side of the gun. The gun and caisson limbers with the horses, ‘drivers’ and the two remaining caisson crew would pull back 300m to the rear so that they would not be engaged by counter-battery fire directed at the guns. In practice, this proved to be too close and the horses and limbers were often hit by fire aimed at the guns. When the battery needed to move, the horses and limbers would be brought forward. The light ammunition columns would deploy 600m behind the gun line and move forward based on flag signals.

The horses were the vulnerable point in an artillery battery. The guns could not unlimber and go into position, or limber up to withdraw, without significant horse casualties if they were in infantry fire at medium range (800m to 1,200m). Under close-range infantry fire (under 800m) the vulnerability of the horses immobilised the battery.

There were two types of battery positions. In the open firing position the guns were not covered or concealed. The gunners could see to their front and directly aim the guns over open sights. The guns were also visible to the enemy. A battery could occupy an open position easily and could fire quickly and effectively, especially against moving targets. It could rely on the gun shields for protection against small arms fire, but in an open position it was visible to enemy artillery and vulnerable to counter-battery fire. Open positions would be used in a mobile battle.

In a covered (or defilade) firing position, the guns went into battery position behind cover or concealment (frequently on the reverse slope of a hill). The guns were aimed by the battery commander, who set up his command wagon in a position where he could observe the enemy; the guns were then laid in for direction from the battery command wagon using an aiming circle (similar to a theodolite) and firing commands (deflection and elevation, type and number of rounds, fuse setting) were usually transmitted by field telephone from command wagon to the guns. Covered battery positions were nearly invulnerable to counter-battery fire, unless the dust thrown up by the muzzle blast betrayed the gun’s position. Frequently the enemy would be reduced to attempting to suppress guns in a covered position by using area fire based on a map reconnaissance of likely covered positions, a procedure that demanded large quantities of time and ammunition. The disadvantage of covered positions was that occupying them was time-consuming, because of the extensive reconnaissance needed to find a suitable position in the first place, followed by the time necessary to lay the battery using the aiming circle. Adjusting fire would take more time than in an open position. Covered positions would be used at the beginning of an engagement, in artillery duels, and against stationary targets and dug-in positions.

There was also a half-covered position, in which the guns were defilade, but could be aimed by the gunners standing on the gun. Such positions were preferable to open positions while at the same time allowing a more rapid support of the infantry that completely covered positions.

Guns could also occupy an overwatch position. The battery was then deployed in a covered position, laid on an azimuth in the general direction of the expected target. When the target was observed, the battery was manhandled into firing position.

If the time and suitable positions were available, the artillery would initially occupy covered positions, but in the course of the battle, the artillery would almost always be forced to displace and fire from half-covered or open battery positions. If necessary the artillery, like the infantry, was to advance by bounds. Some batteries might be moved forward to provide close-range direct-fire support. When the infantry began the assault, the artillery would fire on the enemy defensive position for as long as possible, until the danger of friendly fire became too great (usually 300m) and then shift its fire to the rear of the enemy position. When the enemy withdrew, he would be pursued by fire, with the artillery moving forward at a gallop and on their own initiative, if necessary, to keep the enemy in range.

Prior to the introduction of long-range quick-firing artillery around the turn of the century it was common to employ artillery in long continuous lines. In order to use the terrain effectively and avoid counter-battery fire, artillery was now to be employed in groups. Enemy counter-battery fire was rarely able to destroy a gun or caisson; its usual effect was to suppress the guns by forcing the crews to take cover. For that reason, the crews were to dig revetments around the gun positions as soon as possible, even in the attack.

If the guns came under effective fire, the artillery commanders had to decide, on the basis of the overall situation, whether the gunners could cease fire and take cover, which involved the crews’ retreating several hundred metres, leaving the guns and caissons in place, or if the artillery had to continue to fire, even if it meant that the crews were destroyed or the guns were overrun. Under overwhelming fire the artillery commanders down to battery level were authorised to order the crews to take cover.

It was the responsibility of the artillery to maintain liaison with the infantry through the use of forward observers (FO). The FO would communicate with his battery through field telephones or signal flags. His most important mission was to keep the guns informed as to the relative locations of the friendly and enemy troops, so that as this distance was steadily reduced, the guns could place fire on the enemy for the longest possible time. The artillery also regularly sent forward officer patrols, frequently in conjunction with cavalry patrols, in order to develop targets for their batteries.

The standard shell for gun artillery was shrapnel with a time fuse. The shrapnel shell exploded above and in front of the target, covering the target area with metal balls. In practice, setting the time fuse was difficult and shrapnel often burst too high. There was also a high-explosive round with contact fuse, which was used by howitzers and also by guns.

Beginning in the 1890s the German artillery underwent a profound transformation. In 1890 the cannons were not provided with recoil brakes and gunnery practice took place from open positions at ranges of less than 3,000m. Firing from covered positions was inaccurate and slow. Then the improvements came fast and furious. FAR 69 recorded receiving the light howitzer in 1899, with aiming circle and field telephones to facilitate firing from covered positions. In the spring of 1906 FAR 69 received the cannon with recoil mechanism and gun shield. In 1907 a new artillery regulation introduced a doctrine commensurate with the new equipment and made combat effectiveness the sole standard for training. Firing with time fuses became normal, the field guns received stereoscopic battery telescopes, field telephones (1908) and aiming circles, and armoured observation wagons. Reservists were recalled to active duty to receive training in the new equipment. The German field artillery in 1914 had good equipment and had plenty of time to train with it.

Heavy Artillery

For over twenty years prior to the First World War, the German army worked to perfect its heavy artillery, which involved constructing a mobile 15cm schwere Feldhaubitze 02 (sFH 02 – heavy field howitzer 1902) for the corps artillery and a 21cm mortar for the army-level artillery, and then creating the techniques and doctrine to use them. Originally, the impulse for this development was the need to be able to quickly break the French fortress line, and in particular the Sperrforts located between the major French fortresses. This mission shifted to one which emphasised destroying French field fortifications and finally to counter-battery fire. Particular emphasis was also laid on integrating the sFH into combined arms training, including live-fire exercises. By the beginning of the war, the German heavy artillery was fully proficient in all three missions. No other country in Europe possessed such combat-effective heavy field artillery. French heavy artillery was not so numerous, nor so mobile, nor as technically and tactically effective as the German.

Every German active-army corps included a battalion of four batteries of schwere Feldhaubitze, each battery having four guns, sixteen guns and thirty-two caissons in total. The battalion also had an organic light ammunition column. The reserve corps did not have this battalion, which significantly reduced its combat power.

The 15 cm gun was characterised by the destructiveness of its high-explosive shell (bursting radius 40m to the sides, 20m front and rear), combined with its long range (most effective range 5500m, max effective range 7,450m) and high rate of fire. It was particularly effective against enemy artillery, which was otherwise protected by its gun shield, and against infantry in field fortifications (the shell came down nearly vertically and was capable of penetrating 2m of overhead cover) or in defilade behind masking terrain. It was less effective against moving targets than the field artillery. The heavy field howitzer was less mobile than the field gun, but nevertheless was able to move long distances at a trot. The sFH battalion normally fought as a unit, firing from covered positions.

The 7.7cm gun fired a 6.85kg shell at a rate of up to 20 per minute. The 10.5cm howitzer fired a 15.8kg shell at a rate of four per minute; the heavy howitzer fired a 39.5kg shell at a rate of three to six per minute.

The German army also possessed a mobile 21cm mortar, which was principally intended for assignment at the army level, to be used against permanent fortifications. A mortar battery had four mortars; each battalion consisted of two batteries. The mortar could move only at a walk, the gun being separated for movement into three sections: gun carriage, barrel and firing platform.

The German field army began the war with 808 15cm sFH, 112 21cm mortars, 196 10cm canons and 32 13cm canons; 1,148 mobile heavy guns in total. It had a store of 1,194,252 shells, that is, about 1040 shells per gun.

The French field army, in contrast, had only 308 heavy guns, which were older and technically inferior to the German guns, mostly 155cm ‘Rimailho’ canons that had to be broken down in two sections for movement, with a maximum range of 6,300m. The Germans therefore had 4–1 superiority in heavy artillery. The French also had 380 ‘de Bange’ heavy guns in siege artillery units.

Each French division had nine four-gun batteries; the corps artillery consisted of twelve more batteries. Heavy howitzers were an army weapon; a French corps could not expect to receive more than four guns. The Germans thought that the French would augment each corps with another six reserve batteries, which was not the case. A French corps therefore at best had 120 guns versus 158 (including 16 heavy howitzers) for the German corps. The French began the war with about 1,300 shells for each 75mm.

General Heer, one of the leading authorities on French artillery, wrote a perceptive comparison of French and German doctrines. Heer began by saying that both armies expected the war to consist of manoeuvre battles, and both armies emphasised the offensive. However, the French laid particular emphasis on movement, especially the decisive advantages that accrued to forward movement. The Germans, on the other hand, recognised the importance of firepower and understood how to use it better than the French. The German leadership was convinced that infantry could not advance in the face of modern firepower, and especially not against artillery fire. They considered it essential that the battle begin with systematic counter-battery fire. Live-fire exercises taught the Germans the value of heavy artillery in mobile battles in general, but especially in counter-battery fire. Finally, the Germans decentralised the control of artillery down to division level. There were no corps and army artillery commanders. Thomasson said that the German optical fire control was outstanding, and unknown to the French. It permitted the Germans to be able to adjust artillery fire ‘magnificently’.