The 4th Indian Division began disengaging from the Italians near Sidi Barrani on 12 December 1940. Sixteen days later, the division’s 7th Indian Infantry Brigade – the garrison force at Matruh – embarked on the short voyage to Port Sudan. The 11th Indian Infantry Brigade followed on New Year’s Day 1941, while the 5th Indian Infantry Brigade was moved overland by rail and by Nile steamer. The redeployment was nearly flawless – the only glitch being an Italian air attack on the train carrying the 3/14th Punjab battalion, which resulted in some losses. By the end of January 1941, the entire division was concentrated in the Sudan. The 7th Indian Brigade was deployed to defend Port Sudan and its lines of communication; the rest of the division headed for the Kassala sector, where it was joined by the Gazelle Force. The 5th Indian Division stayed put in the Gallabat sector and engaged in an elaborate deception to divert the Italians’ attention from the coming offensive on Kassala.

Yet again, however, it was the Italians who surprised their adversary. From early January there were indications that the Italian forces might be preparing to withdraw from Kassala. The British commanders hesitated to pre-empt this move, fearing that a hasty attack launched with inadequate forces might prove disastrous. The Italian intention to pull back became clearer by the day, so an operation was planned to prevent the Italian forces from getting away intact. The attack was to be launched by a mixed force of the 4th and 5th Indian Divisions on 19 January. The night before, the Italians gave them the slip. The Indian divisions were ordered immediately to commence a pursuit. The Italian withdrawal lifted the threat to the Sudan and pulled the Indian forces into Eritrea.

The Indian forces pursued the retreating Italians on two axes. In the north, the 4th Indian Division, led by the Gazelle Force, advanced from Kassala to Wachai and thence to Keru and Agordat. The 5th Indian Division took a southerly route from Kassala to Aicota and thence to Barentu and Agordat. The Italians staged a fighting retreat. They had prepared delaying positions on tactically important hills and mined the key approaches. In particular, they offered considerable resistance at Keru and Barentu. The terrain, too, was not suited to a rapid chase by the Indians. The country around Kassala was a desert plain with knee-high scrub and the odd hillock, but to the east of Kassala the hills rose high and the valleys were rocky. And these posed a formidable challenge to the passage of mechanical transport.

A few days after their withdrawal from Kassala, the Italians pulled out of Gallabat as well. The Italian retreat here was less hasty, for they had heavily mined the area. Bhagat’s sappers worked ahead of the 9th Indian Infantry Brigade in clearing this route. ‘The last ten days have been a bit trying,’ he wrote on 10 February 1941, ‘especially as I have had three narrow escapes. Luckily the only damage done is that I have now got a deaf ear.’ Bhagat had been on the road for ninety-six hours, sweeping fifteen minefields over a 55-mile stretch, despite being blown off his vehicle twice and ambushed by the Italians – an astonishing display of courage under fire for which he had just been awarded the Victoria Cross. But he found little glorious about the pursuit of the Italians: ‘The last ten days have been quite a revelation to me of war. Dead bodies lying on the road, some mangled and no one taking any notice of them. To think the same body had life and enjoyed himself a few hours before is preposterous.’

Near Agordat the Italian forces put up a tenacious defence, counter-attacking positions taken by the Indians and bringing to bear accurate artillery fire on the Indian forward positions. Eventually, they broke contact with the Indian forces and retreated further. Agordat was the first town in Eritrea to be captured by the Indians, and its fall prodded Wavell into perceiving greater opportunities in Eritrea. He now favoured a major operation aimed at capturing Asmara itself. He realized that this would thwart his earlier plan of sending forces back to Egypt, but felt that the operations in the Western Desert were ‘going very well . . . there was no immediate need of additional troops in Egypt’. Wavell instructed General Platt to ‘continue his pursuit and press on towards Asmara’. But the road to Asmara ran through Keren.

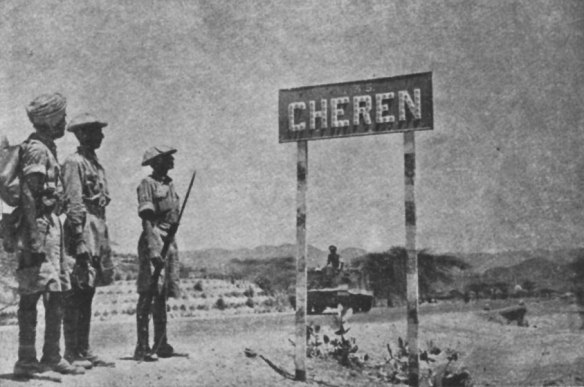

The town of Keren stood on a plateau at a height of over 4,300 feet. The region around Keren, the British realized, was ‘a wild immensity of peaks, knife-edge ridges, precipices, gorges and narrow defiles’. The road from Agordat ran in a north-easterly direction up the narrow Ascidira Valley towards a range of imposing hills that stood guard around the Keren plateau. As the road hugged the lower reaches of these hills, it passed through a narrow cleft – nowhere wider than 300 yards – called the Dongolaas Gorge. Along the eastern wall of the gorge, the road wound its way up to Keren. On either side of the gorge stretched a series of tangled ridges and massifs. To the east lay mounts Dologorodoc and Zeban, Falestoh and Zelale. In the west were the even more formidable mounts Sanchil and Samanna. The Italians had long realized the strategic importance of Keren for the defence of Asmara and had deployed the bulk of their troops there in defensive positions that dominated the high ground and key approaches in the area.

The first assault on the defences of Keren was undertaken by the 4th Indian Division. In the afternoon of 3 February, the 2nd Cameron Highlanders of the 11th Indian Brigade attacked and captured a ridge just south of Sanchil. The feature was promptly dubbed Cameron Ridge. Thereafter, the going was tough. The 3/14th Punjab attacked a peak on Sanchil but were unable to hold it against Italian counter-attacks supported by artillery and machine-gun fire. The 1/6th Rajputana Rifles secured a position to the west of Cameron Ridge, but were eventually dislodged by successive waves of counter-attacks. By the night of 6 February, the Indians were left with only a tenuous toehold at Cameron Ridge. This too was under attack from the Italians. ‘In the ding-dong battle’, Babu Singh of the 3/1st Punjab was injured at around 6 p.m. on 10 February. ‘By then heavy casualties had taken place. Our Colonel . . . who was also injured, announced that there was no arrangement to evacuate the dead and injured, and called upon each man to fend for himself and retreat.’

General Platt now realized that the ‘storming of Keren position was no light task . . . Gaining surprise was unlikely. The forcing of Keren was bound to mean hard fighting and casualties which would be difficult to replace.’ Finding a way around the road and the main Italian defences was evidently desirable. Between Falestoh and Zelale lay a low-slung ridge called Acqua Gap, over which ran a secondary track to Keren. The 5th Indian Brigade of the 4th Division was tasked to capture this gap on the night of 7 February. The brigade was reinforced by a troop of four Matilda tanks. ‘The hope of gaining surprise was very strong and the low morale of the Italian forces was expected to be of considerable help.’ It did not work out like that. The 4/6th Rajputana Rifles came under intense fire and sustained heavy losses on the approach to Acqua Gap. Although the battalion managed to capture parts of the ridge, it position was precarious at daybreak. The entire area and all lines of approach were dominated by Italian positions. The brigade commander decided against deploying his reserves and ordered a withdrawal at dusk.

Beresford-Peirse thereafter decided on a co-ordinated divisional operation for the capture of Keren. In the first phase, the 11th Indian Brigade would capture a peak on Sanchil. In the next, the Gazelle Force with two battalions would take Acqua Gap. The 5th Indian Brigade would then break through to Keren. It was an unimaginative plan that unsurprisingly ended up reinforcing the earlier failures and totting up casualties. By the morning of 14 February, when the operation was finally called off, the Indians held nothing more than Cameron Ridge.

The inability of the 4th Indian Division to crack the Keren defences stemmed from several factors. To begin with, the division suffered from a combination of over-confidence and under-preparation. Flush with success in North Africa, the division believed that it was up against Italian soldiers of the same poor quality and morale as it had earlier encountered. At the same time, it had – even more than the 5th Indian Division – unlearnt its previous skills of operating in such terrain. What is more, not all its troops had been bloodied in the battles of North Africa. A British officer recalled his experience of being shelled by the Italians in Keren: ‘It was the first time I had been under fire and I was quite surprised at first – rather feeling that the enemy was cheating using live rounds on manoeuvres.’

Attacks tended to peter out as the troops neared the enemy positions above them and the artillery fire was lifted. The lack of training was also evident in the inability of troops to hold the features they captured. Most often the defences of these positions were not reoriented fast enough to stave off counter-attacks by the Italians, or indeed to protect against air and artillery strikes. Commanders tended to shy away from night attacks, too; these called for greater levels of training and preparation but also carried greater possibilities of surprise.

Further, all the battalions of the division were organized for mechanical transport, but the terrain rendered movement by vehicles impossible. In consequence, the battalions had to employ one company entirely for porterage. Supplies of water, rations and ammunition had to be dumped ahead of offensives. All arms and ammunition had to be carried by the soldiers up steep hills during attacks. Worse, this had to be done in hot weather – the approach marches tended to sap the strength out of the troops even before an assault commenced. A related problem was the futility of employing tanks in this terrain. Even the light tanks broke down whenever deployed. Hence, regiments like Skinner’s Horse were used as infantry, providing fire support during attacks – a role for which they had no training or experience.

As the 4th Indian Division pondered the lessons of the failed offensives, Wavell informed London of the lack of progress: ‘the enemy has been counter-attacking fiercely and repeatedly shows no immediate signs of cracking’. Ever eager for a victory, Churchill shot back: ‘I presume you have considered whether there are any reinforcements which can be sent to give you mastery at Keren.’ There were none. Wavell was also concerned about the possibility of a German offensive in Libya to bail out the Italians and was worried that the stalemate in Keren would obviate the possibility of moving troops out of East Africa.

After the failure of the 4th Indian Division’s attacks to the east and west of the Dongolaas Gorge, General Platt realized that ‘any further assault on the Keren position would be a major operation’. Both the 4th and 5th Divisions would have to be hurled against the resolute Italians. Logistically, however, it was impossible simultaneously to maintain both divisions in the Keren area and to prepare dumps of supplies for an attack by two divisions. Hence, the 5th Indian Division was pulled back to positions behind Agordat, where it could be supported from the railhead at Kassala.