Close Quarters, by Russell Smith (SPAD XIII & Fokker DVII)

In 1918 German fighter aviation’s progress required simultaneously increasing craft quality and quantity. Several excellent 300-hp single-seaters were likely to appear in 1919. By mid-September 300-hp Nieuports and Sopwith Dolphins were in production; the prototype Spad Herbemont had recently completed “extremely brilliant” tests; and the Béchereau airframe showed great promise. The 2,870-plane program had stipulated 60 Spad squadrons by spring 1918; the 4,000-plane program required 84 by 1 October, which seemed unlikely since in mid-September fighter aviation had only 64 squadrons. Two-seat types were undergoing final tests in the fall. Two-seat fighters—the SEA (Société d’études aéronautiques) with a 375-hp Lorraine engine, the Breguet with a 450-hp Renault or Liberty, and the Morane with a Bugatti 420-hp engine—were under development, but in 1919 fighter aviation’s fate depended entirely upon future developments. Only in November would the army begin to receive the first Hanriot and Spad Herbemont two-seat fighters, with another (the first machine of the new firm SEA created by young designers Henri Potez and Marcel Bloch) offering further prospects. On 19 September GQG determined its needs based on a 4,200-plane program.

Aviation’s politics and administration stabilized considerably in 1918. Daniel Vincent’s February article posited that the press constantly raised public concern about aviation because the air arm lacked a doctrine of industrial production. Jacques Mortane followed Vincent’s editorial with a call for an air ministry, noting that Britain had an air ministry and Germany possessed a “dictator of the air” in Hoeppner. The call for an air ministry would make no progress during the war. The political clamor for change remained focused on the lack of strategic bombers, though some key air advocates implied the need for an air ministry by attributing all deficiencies to the absence of unified control.

While 1918’s battles confirmed the French high command’s use of bombers against battlefield objectives and enemy transport, the GQG still faced vigorous and persistent criticism in parliament and the public arena from advocates of strategic air power. Premier Georges Clemenceau and Minister of Munitions Louis Loucheur supported the high command before parliament. On 5 April Loucheur, emphasizing the importance of strafing enemy columns, asserted that French and British aviation had retarded the enemy’s arrival on the battlefield by one to two days, while Clemenceau on 3 June gave bomber attacks on the battlefield partial credit for halting the recent enemy advance. On 3 August, after the first summer offensive, Loucheur stressed the importance of demoralizing the Germans by bombing their rear.

Still, parliamentary deputy Pierre Etienne Flandin continued to advocate strategic bombardment in 3 July and 18 September reports. Clemenceau had written him that concentration of forces was essential to victory, and that operations against enemy cities, though possibly of economic and morale importance, were only secondary. Flandin criticized the limited scope of France’s military chiefs and the “narrow doctrine of conduct of the war” that attributed only moderate importance to attacking the industries that produced war materiel. All parliamentary deputies and the high command as well, as General Pétain’s requests indicated, regretted the industry’s inability to perfect a long-range bomber. The deputies, however, had placed top priority on the bomber, but for the high command the long-range bomber was only one of many desired types.

In the military administration of aviation technology and production, 1918 was the era of the technocrats. Martinot-Lagarde of the aero-engine section and Legras of the propeller service—both graduates of the École Polytechnique—were joined in 1918 by another polytechnician, 38-year-old Albert Caquot, whom Colonel Dhé and Dumesnil appointed director of the STAé on 11 January 1918. In 1914 Caquot, a bridge builder, specialist in reinforced-concrete construction and aviation, and an advocate of organizational solutions to problems, had designed a stationary observation balloon, whose streamlined form made it superior to the German Drachen in its ability to remain steady in high winds. After having created an observation balloon for the British fleet in 1916, Caquot had been sent to Britain in 1916 to direct the British fleet’s use of captive balloons against submarines. Caquot balloons formed barrages above London and Paris to protect against German bombers.

At STAé Caquot now dealt with airplanes, at a time when the inability to perfect new materiel threatened to compromise the Allies’ opportunities for aerial supremacy. The problem lay, as it had in 1917, in the Spad 13 and its 220-hp Hispano-Suiza engines. The prototype engine had passed its tests, but some 10,000 production engines had failed their 10-hour acceptance tests, usually through a seizure that left a “salad” of connecting rods or destroyed the crankcase. Caquot ordered the tests of 10 engines. He stopped the first after one hour, the second after two, and so on, to open the crankcase and dismantle the moving pieces. After four hours the cause of the problem became apparent. The oil pipe in the crankcase had broken under pressure, though the engine continued to run for a time.

Caquot attributed the difference in performance between the prototype and the series to weather. The prototype had been tested in warm weather, while the series appeared in the winter. The viscosity of the oils used in 1917 varied greatly with the temperature, and their thickening in the winter led to excessive pressure in the Hispano-Suiza’s oil-circulation system. Technicians had to decrease the oil flow to limit its pressure to a level that the pipe could withstand. After Caquot designed a simple, inexpensive safety valve for the end of the oil pump, Hispano-Suiza production continued.

Caquot’s solutions did not always work. His addition of bracing struts to correct the Morane fighter’s weakness in dives reduced its performance so that it was relegated to training. Yet in most crucial situations, his genius for diagnosing a problem and finding a simple solution benefitted the air arm. When the front complained about excessive Breguet 14 modification, Caquot settled on a mass production aircraft, which was then license produced by large manufacturers such as Michelin. Caquot’s transmission of U.S. propeller research to French manufacturers enabled them to improve their airscrews. Ultimately, Caquot generously surrendered all his rights to the French state at no charge and received medals from all the major Allied powers and gratitude from the French government.40

Caquot praised Minister of Munitions Loucheur’s further mobilization of aviation. Between three and five times a week the directors of the technical and production sections met with Dhé, Duval, and Loucheur or Loucheur’s adviser, engineer Ernst Mercier, to plan the air service’s development. They then met with the industrialists once a week to set production schedules. By May an editorial in La Guerre aérienne, “L’Arme à deux têtes” (the arm with two heads), praised the division of labor between the undersecretary and the munitions ministry. The undersecretary, as the client, selected and perfected types and then, in consultation with GQG, determined the quantity needed, while the ministry, as the supplier, managed serial production. From the spring to the war’s end La Guerre aérienne tended to praise the rear’s organization. An editorial in early June lauded the STAé’s efforts in converting theoretical programs from the front into technical specifications for engineers and builders and asserted that the STAé had clearly outdone its less organized German counterpart and a German industry that was more dispersed and less standardized than the French. In an early August editorial it recognized that fundamental to aviation’s “new phase of its evolution”—collective effort as opposed to individual action—was the French industrial effort, which enabled the new doctrine. In September the journal concluded that quality and quantity determined the command’s aerial tactics, which had left the realm of improvisation and had now become part of a methodical plan, in which aviation was indispensable as an arm of military intelligence and destruction.

In 1918 Loucheur and the aviation agencies attempted to control prices and increase licensed production. In mid-April he considered the aviation service’s contract justifications absolutely insufficient to determine whether prices were too high and insisted that the contract service under Commandant Guignard be placed under Colonel Weyl in the munitions ministry, who would collaborate with Guignard. The prices of Hispano-Suiza 200-hp engines dropped from 18,000 to 22,500 francs at the end of 1917 to 17,500 to 18,000 in mid-1918.

A report in October 1919 contended that the Hispano-Suiza should have cost 8,500 francs, allowing for a net engine cost of 4,500, 15 percent profit, a 10 percent allowance, and 150 percent for general costs and labor. Yet such postwar calculations appear unrealistic, and Dhé justified the prices with the state’s wartime need to develop aero engine production. Builders had used their profits to remunerate capital invested in the enterprise and to expand plant capacity, while continually rising material and labor costs made such calculations of net cost purely theoretical. The aviation service could not requisition engines or militarize factories because it lacked qualified technical personnel to assure production at commandeered factories, so the directorate had emphasized engine quantity and quality above all else. While the French airplanes lacked the finesse of the German Fokkers with their thick cantilever wings, Capt. Albert Etévé of the STAé emphasized the quality, officially called rusticité, characterized by the adoption of very simple construction procedures allowing numerous airframes to be built quickly and cheaply.

With further increases in licensed manufacture, in 1918 subcontractors played a decisive role in aviation production. They reaped 61.9 percent of the total business in 1918, up from 27.3 percent in 1916 and 35.1 percent in 1917. In airframe manufacture the subcontractors’ market share rose from 16.2 percent in 1916 to 43.7 percent in 1917 to 61 percent in 1918. In engine manufacture, it declined from 32.9 percent in 1916 to 27.2 percent in 1917, because of Hispano-Suiza’s introduction of its 200- to 220-hp engine and Salmson’s launching of its 200- to 260-hp series engine, but then it rose to 62.7 percent in 1918. Thus, in 1918 the dominant or parent manufacturers had 38.1 percent of the market: the aircraft producers and engine manufacturers had 39 percent and 37.3 percent of their markets, respectively.

Circumstances within the industry varied. Hispano-Suiza built 14.8 percent of its 25,741 engines in 1918; its 14 subcontractors, which included Peugeot, constructed 85.2 percent. The parent firms Spad and Blériot reaped 17 and 26 percent of the profits respectively on Spad production in 1918, and their subcontractors gained 57 percent. Breguet earned 13.7 percent of the profits from Breguet 14 production in 1918; its subcontractors, which included Michelin and Renault, obtained 86.3 percent. Firms like Renault and Salmson, however, did not subcontract their production.

The aircraft industry remained centered in Paris and its suburbs, where 90 percent of French planes were built, despite limited decentralization in 1918 during the German advances toward Paris. Among the largest factories were Farman, with some 5,000 workers, and Nieuport, with 3,600 workers. The general condition of the factories was good, and most of them were entirely or partially fireproof. The larger companies had assembly plants, and the smaller ones had assembly shops. Women painted, varnished, stretched cloth over frames, and did light woodwork. Assembly rooms were well ventilated to release varnish fumes that could cause eye inflammation, headaches, or stomach trouble, and employees who worked in the varnish room fortified themselves with milk. Large factories had surgical stations staffed by trained nurses. The ordinary working day was 10 hours. Employees were paid 1.5 to 3 francs an hour or by piece, while foremen and staffs were paid monthly. Generally, the number of engines obtainable determined production. French standardization and coordination of production impressed American attaché H. Barclay Warburton in July as offering the potential for large-scale inter-Allied standardization of Spad production, despite enormous difficulties with political and industrial interests.

In 1918, of 41,336 engines manufactured in France through November, 29,461 were stationary engines (V types or in-lines), 5,526 were radials, and 6,349 were rotaries, a dramatic change from the 1917 proportions, in which rotaries and stationary-engine deliveries were nearly comparable (10,757 to 11,395) and radials were relatively scarce (1,223). As orders for rotary engines declined, Gnome and Rhône shifted to producing the Salmson Canton-Unné radial.

In August it took an average of 6.29 workers per month about 250 hours to manufacture a Hispano-Suiza engine. The Hispano-Suiza was one of the most easily constructed wartime engines, since in its parts design Birkigt had been preoccupied with ease of production and had created special machine tools and machines to produce complicated and delicate parts. In 1918 15,108 Hispano-Suiza 200- to 220-hp engines were delivered, only 956 by the parent company; the largest numbers, 4,451, 2,239, 1,784, 1,470, and 1,410, were delivered by Peugeot, Mayen, Brasier, Fives Lille, and Delaunay, respectively. Another 2,166 300-hp engines were delivered in 1918, 814 by the parent company.

In 1918 Renault doubled its engine production from 2,470 in 1917 to 5,050 and nearly trebled its aircraft production from 290 to 870 in its second year of aircraft assembly. From 1 October 1917 to 30 September 1918 Renault’s sales of aero engine and airframes came to 29.3 and 5.5 percent respectively of its total business.

Even with the most successful aviation production apparatus in the world, the French still needed imports in certain categories. France needed more Breguets than Renault could deliver engines and secured Fiat A12bis 300-hp engines from Italy, although the Fiat Breguet was inferior to the Renault-Breguet. France received some 2,200 Fiats. The undersecretary in late August was still seeking a firm agreement on an order of 1,800 Fiats placed the previous month, although France had only delivered 800 of the promised 4,200 tons of raw materials to Italy in return. English and U.S. competition for the Italian engines, since Italian firms were already preparing for peacetime, made arrangements difficult. In September Martinot-Lagarde was in Italy to secure more Fiat A12bis engines as quickly as possible and to remedy the engine’s defects. Aircraft expert Dorand looked to Italy and England as potential sources for Caproni and Handley Page night bombers respectively.

Yet the search for engines indicated a temporary decline in powerful-engine production, not a lack of their development. At the Armistice the French were introducing the next generation of lighter, more powerful, mostly water-cooled engines: the 300-hp Hispano-Suiza V8, 450-hp 12-cylinder Renault, and the 400-hp Lorraine-Dietrich, as well as a 16-cylinder, 450-hp Bugatti, and a 500-hp Salmson twin-row radial.

In 1918 the French aviation industry produced 24,652 airplanes and 44,563 engines. Its monthly aircraft production rose from 1,714 in January to 2,362, its peak, in October. Its monthly aero engine production increased from 2,567 in January to a high of 4,196 in October. In November 1918 it employed 185,000 workers. Twenty-three percent were women, who were most numerous as textile workers in the airframe factories, where they composed a third of the work force. At the Armistice the production service, which had grown from fewer than 20 officers before mobilization to 540 officers and 3,000 personnel, was delivering a plane, completely equipped, armed, and with replacement parts, every 15 minutes, day and night, and a motor, complete with all accessories, every 10 minutes.

On 19 November parliamentary deputy D’Aubigny assessed the state of French aviation at the Armistice. He charged that France had not fulfilled its promises to the United States, which had only 642 planes in line at the Armistice, 50 percent fewer than promised for 1 July. In October France had only 2,639 planes at the front, all of them what he termed obsolete Spad 7s and Spad 13s and obsolescent Breguet 14s. The absence of heavy bombers to perform reprisal raids on German territory particularly annoyed him, since the army subcommission had long advocated them. The quality of French observation planes was inferior, with no hope for improvement in 1919. The new Nieuport and Sopwith fighters did not fully benefit from the 300-hp engine, while the Béchereau frame was still not ready. His previous 3 May report had criticized the absence of unified direction for aviation, and he now attributed all of aviation’s problems to its lack of guidance. The politicians of the aviation commission, still dissatisfied with France’s failure to develop strategic airpower, thus ended the war on a negative note.

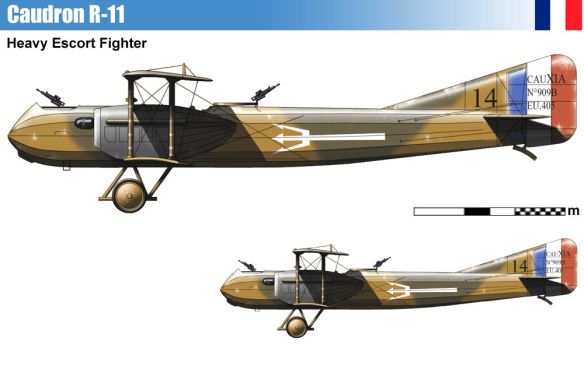

Yet D’Aubigny’s assessment was excessively negative. Perhaps the service lacked unified leadership, perhaps its aircraft were not as modern as the politicians and General Pétain desired. Still, its procurement apparatus had obtained more materiel from its industry than any other country. At the 11 November Armistice, French aviation comprised 247 squadrons with 3,222 aircraft on the Western Front (France’s Northeastern Front): 1,152 fighters, 1,585 observation planes, 285 day bombers, and 200 night bombers. The Aerial Division had 6 combat groups of 432 Spads, 5 bomber groups of 225 Breguets, and 4 squadrons of 60 long-range escort Caudron RIIA3s, for a total of 717 planes. Independent combat units comprised 42 squadrons of 720 Spads, 5 night bomber groups totaled 200 bombers, mostly Voisins, and 148 squadrons of 1,585 observation planes included 645 Breguets, 530 Salmsons, 305 two-seat Spads, 30 Caudrons, and 75 Voisins. The air arm had fallen 348 fighters and 575 bombers short of the 4,000-plane program, which anticipated having 1,500 fighters, 1,000 bombers and 1,500 observation planes at the front. Yet in depots there were nearly 2,600 airplanes waiting in the General Aviation Reserve. On all fronts the French air service had 336 squadrons, operated by 6,417 pilots, 1,682 observers, and 80,000 nonflying personnel. In air strength it was the world’s largest air force.