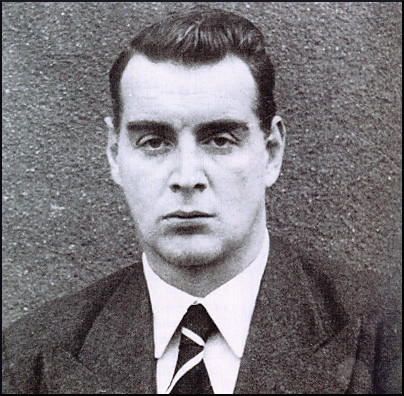

Guy Burgess

The prime mover initially was Guy Burgess, a flamboyant Old Etonian whose Communist leanings were inflamed further by the book Hitler over Europe? by Ernst Henri, which proselytized the use of cells containing five members (Fünfergruppen, as they were named in Germany) to help foment anti-fascism. Henri was in fact OGPU agent Semyon Nikolayevich Rostovsky, who was a major recruiter for Moscow Centre, talent-spotting in Cambridge during the thirties. Burgess set out to create his own ‘light-blue ring of five’.

Around the same time, one of his friends, former Cambridge man Harold ‘Kim’ Philby was signing up for Soviet Intelligence. Philby graduated in 1933 with ‘the conviction that my life must be devoted to Communism’. He travelled in Europe, and in Vienna met and married Litzi Friedmann, who was a Comintern agent, and attracted the attention of the OGPU for his work on behalf of the party. He was recruited by Teodor Maly, and according to Philby, at that stage ‘given the job of penetrating British intelligence . . . it did not matter how long it took to do the job’. He was sent back to England in May 1934 with a new controller, Arnold Deutsch, code name Otto.

Deutsch was instructed to work with both Philby and Burgess, but when Philby unsuccessfully tried to join the civil service (he was passed over because his referees had doubts about his ‘sense of political injustice’), Deutsch ordered him to be patient. Philby therefore publicly claimed to have changed his political orientation, and started to become a member of the establishment, working for the liberal monthly Review of Reviews.

Burgess had been busy, gathering his ring of five. They included mathematician Anthony Blunt, and language scholar Donald Maclean, both of whom were Burgess’ lovers at different times. He also recruited another modern languages student, John Cairncross, into his Comintern cell.

When Burgess was formally recruited by Deutsch, the controller suggested that the idea of a group was perhaps not the best way forward. Burgess, though, maintained the links of friendship between the five men throughout the next few years – which would almost prove catastrophic for Kim Philby when he was tarred by association with Maclean and Burgess when they were forced to defect to Russia in 1951.

On Deutsch’s instructions, Maclean and Cairncross both broke off their contact with the Communist party, and applied to join the civil service. Burgess became personal assistant to MP Jack Macnamara; Maclean was accepted into the Foreign Office in October 1935, with Cairncross joining him there a year later. While the personable Maclean made friends and started to gain access to useful material, Cairncross was less successful, and eventually Deutsch suggested that he apply to work at the Treasury. Burgess became a popular producer for the British Broadcasting Corporation, making contacts across the spectrum – including MI6 deputy department head David Footman, who would recommend Burgess for a job in the secret service in 1938, working for MI6’s new Section D, broadcasting propaganda to Nazi Germany. Blunt remained in Cambridge, sourcing new recruits for the NKVD, including Leo Long, who would be an important asset during the Second World War.

Philby, meanwhile, was becoming involved in the sort of assignment more usually to be found in the contemporary thrillers of Helen MacInnes or Leslie Charteris than the more mundane copying of secrets and passing of information carried out by the other Cambridge Spies. The Spanish Civil War broke out in 1936, and early the next year, Philby was sent under journalistic cover to penetrate General Franco’s entourage and help organize his assassination. That particular mission was abandoned that summer in favour of gaining information about the other intelligence services operating in Spain. The following spring, Philby became a local hero when the car he was travelling in was hit by a shell and he was the sole survivor; the medal he received was pinned on by Franco himself!

The Magnificent Five, though, were shortly to find themselves without a controller. Following the great purges of the NKVD in 1937, both Maly, who had been working with Philby, and Deutsch were recalled to Moscow. Maly faced execution, while Deutsch survived into the war years before being executed by the SS as part of the anti-Nazi resistance in Vienna.

When war broke out, the Magnificent Five ensured that they were in prime positions to assist their Soviet paymasters. Cairncross became private secretary to Lord Hankey, the Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, who chaired many secret committees and was even overseeing the intelligence services. This meant that Cairncross could pass across ‘literally tons of documents’, according to the NKVD, including warnings about Operation Barbarossa, and the findings of the Scientific Advisory and Maud Committees regarding the prospect of creating a weapon using Uranium-235 – making him one of the Soviet Union’s first atomic spies. When Hankey was sacked from the Government in 1942, Cairncross turned his attentions to Bletchley Park, home of the Engima codebreakers.

Burgess was already ensconced in MI6 at the outbreak of war, and he assisted Kim Philby’s smooth entry to the organization. Philby and Burgess would work together as instructors at a training school for the sabotage division Section IX (known as Section D, for ‘Destruction’) before that was folded into the new SOE. Burgess was let go while Philby remained with SOE until he moved across to Section V, the Counter-Intelligence section of MI6. (Moscow had other agents in SOE, including Donald Maclean’s schoolfriend James Klugmann.)

While at Section V, Philby was able to pass on information on pre-war MI6 agents operating against the Soviets from the Registry, and, by volunteering for night duty at service headquarters at 54 Broadway, near St James’ Park in central London, he could keep Moscow informed of all current developments. He liaised with MI5 when Section V moved into central London in 1943, and when a new Section IX was established in 1944, specifically to deal with the Soviet threat past and present, Moscow Centre insisted that he ‘must do everything, but everything, to ensure that [he] became head of Section IX’. Philby manoeuvred the main contender – a staunch anti-Communist – out of the running, and as his colleague Robert Cecil wrote, thereby ‘had ensured that the whole post-war effort to counter Communist espionage would become known in the Kremlin. The history of espionage records few, if any, comparable masterstrokes.’

Although Philby undoubtedly made the greatest contribution overall to Soviet intelligence, during the war it was Cairncross and Blunt who attracted the most plaudits from Moscow Centre. Blunt would eventually work himself into a nervous breakdown, and effectively become little more than a courier after the war. He was recruited into MI5 in the summer of 1940, and was soon in charge of surveillance of neutral embassies, as well as gaining surreptitious access to the various diplomatic bags of their couriers – which he would photograph and pass over to the Five’s new London contact, Anatoly Gorsky. He also ran Leo Long as a sub-agent, gaining material courtesy of Long’s access to ULTRA material from Bletchley Park as a member of MI14.

Cairncross was also at Bletchley at this point early in the Second World War, passing on information about German troop movements, and contributing to the Soviet victory at the Battle of Kursk. In 1944, he then moved across to MI6, working on the German desk at Section V, before moving to the Political Intelligence section, where he didn’t prosper so well, lacking Burgess’ or Maclean’s innate talents for getting along with people easily.

Guy Burgess’ contributions to the Soviet war effort were in a different field, following his dismissal from SOE. He ended up working once more as a talks producer for the BBC, and even managed to get the author of his own inspiration, Ernst Henri, on the air, proclaiming how great the Soviet Union’s intelligence network was!

Maclean was the only one of the Five not to have a distinguished war career – at least at first. He didn’t handle the strain of his double life well, and although he was part of the General Department of the Foreign Office, he seemed to lack energy, not helped by problems with his domestic life. However in Spring 1944, he was posted to Washington DC, and seemed to regain his previous enthusiasm. He had access to information about the Allies’ plans after the war ended, and also became involved with liaison with the atomic-bomb project. His wife was in New York, and he travelled there from Washington regularly to see her – and pass on information to Gorsky, who had crossed to the United States to handle Centre agents there. Of course, this meant that there was signals traffic between the various Soviet missions on the East Coast regarding his movements – something that would come back to haunt Maclean a few years later, and eventually cause the downfall of the entire Cambridge Magnificent Five.

Compared with their British or Russian allies, the Americans were latecomers to the espionage field – partly, of course, because as of the start of the Second World War, the United States as an entity had only existed for just over 150 years.

During the First World War, which America only entered in 1917, the Army’s G-2 section along with the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) had operated against pro-German groups, and American cryptologist Herbert O. Yardley helped to organize the US Army’s Cipher Bureau, known as MI-8. This had some notable successes against German agents operating in the US, but its peacetime operations were brought to a close in 1928 when incoming president Herbert Hoover’s new secretary of state Henry L. Stimson shut it down, stating that ‘Gentlemen do not read each other’s mail’.

G-2 and the ONI continued to function between the wars, working in tandem with the newly created Federal Bureau of Intelligence (formerly the Department of Justice Bureau of Investigation) to keep an eye on actual and potential subversive elements, including the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA). It seems they didn’t realize the scale of Soviet infiltration: the daughter of the American ambassador to Germany was an early recruit, while Congressman Samuel Dickstein, a key member of the Special Committee on Un-American Activities, which was seeking to eradicate Nazism in the States, was on the NKVD books during the late thirties, and earned the nickname Crook for his financial demands.

Inevitably there were overlapping operations between the various groups, but it was only after the outbreak of war in Europe in September 1939 that President Roosevelt decided to regularize the situation. In June 1940, internal security was divided between the various parties: the FBI remained in charge of civilian investigations, while G-2 and the ONI dealt with those involving the military (including defence plants that had major Army or Navy contracts). They would also be responsible for the Panama Canal Zone, the Philippines and major Army reservations.

Despite the shutdown of the Cipher Bureau, code-breaking had continued to form a major part of the intelligence work of the US forces, and a debate continues to this day about how much was known by President Roosevelt about the impending attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941. It seems probable that the president was not aware of the danger, but what is absolutely certain is that the men in charge in Hawaii were not up to speed with everything that Washington knew and didn’t take the appropriate action. The code-breakers would redeem the reputation of their profession by breaking the Japanese code known as JN25, which prevented the invasion of Northern Australia and gave US Fleet Admiral Nimitz a vital edge before the Battle of Midway.

Five months before Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt appointed William ‘Wild Bill’ Donovan, a successful Wall Street lawyer and Medal of Honor winner, as Coordinator of Intelligence (COI). Donovan had spent the previous year liaising with William Stephenson, the Scottish-Canadian millionaire who became an unofficial channel for British influence in the States following the outbreak of war in Europe. Donovan became convinced that a central coordinated American intelligence agency was required, and his appointment as COI, consulting with the heads of the existing agencies and reporting directly to the president, was a major stepping-stone towards that.

The declaration of war with Japan and Germany in December 1941 led to a division of the COI’s responsibilities, with its propaganda work transferred to the Office of War Information, and the rest incorporated into the new Office of Strategic Services (the OSS). Donovan remained in charge of this new organization, but instead of reporting to the president as formerly, he now answered to the military Joint Chiefs of Staff.

The OSS was split into three divisions: the Special Intelligence division gathered intelligence from open sources, and from agents in the field. Allen Dulles was in charge of a crucial station in Bern, Switzerland, which supplied a lot of vital information regarding the Nazi rocket programme, and the German atomic bomb project. The Special Operations group was an equivalent to the British Special Operations Executive, and carried out many of the same functions, sometimes in tandem with the British, but on other occasions, as in Yugoslavia, working with different groups opposing the Nazis. The Morale Operations division used the radio station Soldat Ensender as a propaganda weapon against the German army. Many senior figures in American intelligence circles after the Second World War were OSS agents, including future CIA chiefs Allen Dulles and William Colby.

Although the FBI were involved with what might be termed traditional activities during the war years – dealing with potential saboteurs and other threats to national security – they did operate their own Special Intelligence Service (confusingly referred to as the SIS by the Bureau) in Latin America. According to the FBI’s own history its role ‘was to provide information on Axis activities in South America and to destroy its intelligence and propaganda networks. Several hundred thousand Germans or German descendants and numerous Japanese lived in South America. They provided pro-Axis pressure and cover for Axis communications facilities. Nevertheless, in every South American country, the SIS was instrumental in bringing about a situation in which, by 1944, continued support for the Nazis became intolerable or impractical.’

At much the same time as the heads of British Intelligence were contemplating what would happen once the Axis was defeated, William Donovan was considering the future for American Intelligence. In a memorandum to President Roosevelt on 18 November 1944 he wrote:

Once our enemies are defeated, the demand will be equally pressing for information that will aid us in solving the problems of peace. This will require two things:

- That intelligence control be returned to the supervision of the President.

- The establishment of a central authority reporting directly to you, with responsibility to frame intelligence objectives and to collect and coordinate the intelligence material required by the Executive Branch in planning and carrying out national policy and strategy.

This central authority would be led by a director reporting to the president, aided by an Advisory Board consisting of the Secretary of State, the Secretary of War, the Secretary of the Navy, and such other members as the President might subsequently appoint. Its primary aim would be to coordinate all intelligence efforts and the collection ‘either directly or through existing Government Departments and agencies, of pertinent information, including military, economic, political and scientific, concerning the capabilities, intentions and activities of foreign nations, with particular reference to the effect such matters may have upon the national security, policies and interests of the United States’.

The memo was leaked to the press, and caused an uproar. Columnist Walter Trohan said that it would be ‘an all-powerful intelligence service to spy on the post-war world and to pry into the lives of citizens at home’ which ‘would operate under an independent budget and presumably have secret funds for spy works along the lines of bribing and luxury living described in the novels of [British spy novelist] E. Phillips Oppenhem’.

Roosevelt took no action on Donovan’s suggestion, and, following the president’s death, his successor Harry S. Truman decided not to allow the OSS to continue post-war, fearing that it would become an ‘American Gestapo’. The order to disband was given on 20 September 1945, and the OSS ceased functioning a mere ten days later, with some of its key capabilities handed over to the War Department as the Strategic Services Unit.

Yet only four months after he had seen fit to shut down America’s key central intelligence-gathering organization, President Truman signed an executive order establishing the Central Intelligence Group to operate under the direction of the National Intelligence Authority. What had changed?