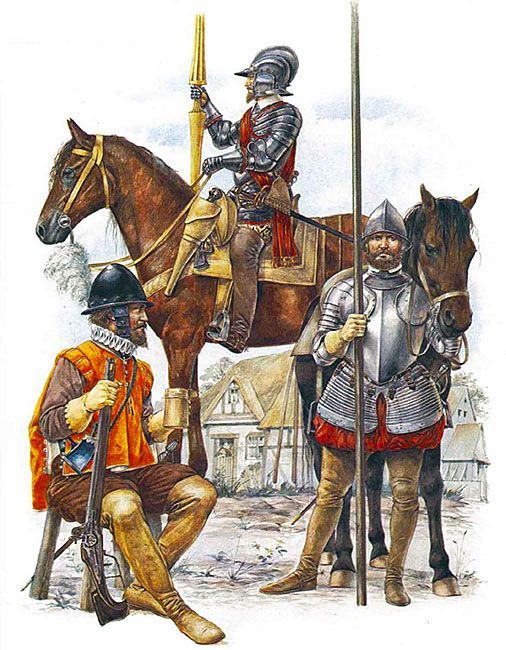

“The Armada Campaign, 1588: • Petronel, Earl of Essex’s troops • English demilancer • English light horseman”, Richard Hook

English; The Armada Campaign, 1588- English Officer, English caliverman & English pikeman by, Richard Hook

In 1585, Elizabeth I turned to open war with Spain and sent an army under Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, to preserve the United Provinces of the Netherlands from Spanish reconquest. The English army fought unremarkably but saved the United Provinces from immediate collapse. England’s limited political and financial commitment to the Netherlands, Dutch factional politics, and the ambition of Holland to lead a decentralized Dutch confederacy together sank Leicester’s ambition to set up a centralized Dutch government under English aegis. The expedition, although in many ways a failure, preserved the United Provinces and left behind a looser, more durable Anglo-Dutch alliance for the remainder of the war with Spain.

The 1584 assassination of William of Orange left the Netherlands Revolt on the verge of collapse as the Spanish overran most of Flanders and Brabant. Elizabeth therefore reluctantly moved to open war against Spain in 1585, signed the Treaty of Nonsuch (1585) with the United Provinces, and agreed to send an English army of 5,000 foot soldiers and 1,000 cavalry to the Netherlands. Elizabeth also sent English garrisons to the four cautionary towns of Brill, Flushing, Ramekins, and Walcheren; these garrisons freed Dutch troops for field service and guaranteed England’s political, fiscal, and military interests in the United Provinces. Elizabeth appointed Leicester to lead the expedition. Leicester, the queen’s favorite, a member of the Privy Council and a longtime advocate of English intervention on behalf of the United Provinces, was the natural candidate for the position.

Leicester arrived in the Netherlands in December 1585; he stayed until November 1586 and returned again between June and December 1587. In January 1586 Leicester accepted the position of governor-general of the United Provinces, so as to forward their political centralization and provide for a more efficient organization of the Dutch armies. Leicester accepted the appointment without consulting Elizabeth and against her desire to eschew any formal English suzerainty over the United Provinces; he provoked her to a bout of fury against him, which, although temporary, permanently damaged his prestige. Leicester’s tenure in the Netherlands suffered from Elizabeth’s desire to minimize her commitments to the United Provinces; she miserably underfunded Leicester’s army and confined it to a largely defensive role. Elizabeth’s preference for a peace treaty with Spain that preserved English interests, even one that sacrificed Dutch independence, was an open secret that alarmed the Dutch and inflamed their mistrust of Leicester.

Leicester created further conflicts with the Dutch governing elites by attempting to centralize under his own authority the government of the United Provinces; to forbid Dutch merchants (most importantly those of Holland) from selling war materiel and provisions to the Spanish enemy; and to promote a Leicesterian party throughout the United Province, heavily composed of local opposition factions, Calvinists unhappy with the Erastian tone of the Dutch religious settlement, and exiles from the Spanish-occupied southern Netherlands eager to promote an aggressive Dutch military policy. In response, the Dutch elites withheld their political and fiscal cooperation from Leicester-not least by refusing to pay the English troops-and began to promote Maurice of Nassau, the young son of William of Orange, to positions that could check Leicester’s authority. Holland in particular sabotaged Leicester so as to promote its own leadership within a decentralized Dutch confederation. Leicester’s final withdrawal from the Netherlands registered the failure of his policies and the triumph of Holland.

The English military effort, meanwhile, had been at best mediocre in its results. The untrained, badly paid English levies fought little, and largely defensively- partly because Elizabeth wanted them to do nothing more and partly because they were incapable of effective offense. In the summer of 1586, the Spanish took Grave, Venlo, and Neuss, but Leicester then oversaw the surprise capture of Axel and the successful storm of a Spanish fort near Zutphen. These successes, however, were followed by the treasonous surrender to the Spanish in January 1587 of the Zutphen fort and the town of Deventer by English Catholics Sir William Stanley and Rowland York-officers picked by Leicester, whose loyalty he had guaranteed. This treason outraged and horrified the Dutch and sent Anglo-Dutch relations to a nadir; English soldiers starved in the winter of 1586-1587, to great Dutch indifference. In July 1587, Sluys surrendered to the besieging Spanish despite Leicester’s best efforts to relieve the town. The Dutch avoided further major losses of territory after Sluys only because the Spanish had begun to prepare for the invasion of England.

Further Reading Adams, S. Leicester and the Court. Essays on Elizabethan Politics. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 2002. Hammer, P. E. J. 2003. Elizabeth’s Wars. War, Government and Society in Tudor England, 1544-1604. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003. Oosterhoff, F. G. Leicester and the Netherlands, 1586-1587. Utrecht, Netherlands: HES, 1988.