Fought on 10 September 1547, along the Firth of Forth near Musselburgh, southeast of Edinburgh, the Battle of Pinkie marked the beginning of a new phase in the Rough Wooing, the sustained English attempt to compel the Scots to accept a marriage between their queen and the English king. The overwhelming English victory destroyed the main Scots field force, allowed the English to establish garrisons across southern Scotland, and brought the French into the war on the Scottish side.

When the Scottish Parliament repudiated the Treaty of Greenwich in December 1543, Henry VIII launched successive invasions of Scotland to force acceptance of the main provision of the treaty, the marriage of Mary Stuart, Queen of Scots, to Prince Edward, the future Edward VI. At Henry’s death in January 1547, the Scots remained defiant. Because of the king’s youth, control of the English government passed to Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset, who, as the king’s eldest uncle, assumed office as lord protector. In Scotland, the government of the even more youthful queen was headed by James Hamilton, Earl of Arran, the heir to the throne, who worked in uneasy partnership with a pro-French party led by the queen mother, Marie de Guise.

In late August 1547, while massing a force of more than 16,000 on the border at Berwick, Somerset issued a proclamation to the people of Scotland reminding them of the 1543 agreement and of the history and geography they shared with the English. His army, he claimed, was coming not to threaten Scotland, but “to defend and maintain the honor of both the princes and realms” (Jordan, Edward VI, 252). Crossing the frontier on 31 August, the English marched along the coast toward Edinburgh, supported on their flank by a fleet under Edward Fiennes de Clinton, Lord Clinton. Moving swiftly, the English seized castles along their line of march and dispersed harassing bands of Scots. On 9 September, Somerset encountered the main Scottish force, 20,000 in number, holding a strong position along the river Esk.

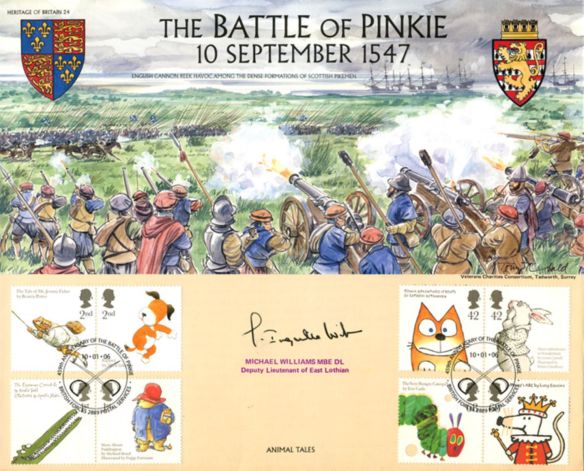

Next morning, Somerset ordered his right wing to assault the Scottish line, thereby shifting the entire army toward the Forth and the protection of Clinton’s guns. Arran, in command of the Scottish force, misinterpreted the movement; he believed Somerset was trying to avoid an engagement by taking his men to the coast for embarkation on the fleet. Arran accordingly ordered the Scots to leave their well-prepared defenses and attack. Seeing the Scottish movement, Somerset halted his army and formed line of battle. The Scots, far inferior to the English in cavalry, had no cover for the flanks of their pikemen, the same bristling formations of spearmen that James IV had used at Flodden Field. Slowed by cavalry charges and broken by artillery, the Scottish formations disintegrated, and the battle degenerated into a slaughter as the English infantry pursued the fleeing Scots to the gates of Edinburgh.

While English losses numbered 500 to 600, the Scots lost 10,000 or more. Organized Scottish resistance ceased, and Somerset spent the following months securing southern Scotland by seizing strongpoints and establishing a web of English garrisons centered on the fortress at Haddington. Thanks to French inducements- Arran was given the title Duke of Chatelherault-and the efforts of the queen mother, the Scots turned in this emergency to their ancient ally, France. Concluded in July 1548, the Treaty of Haddington promised the Scots French military assistance in return for the marriage of their queen to the eldest son of Henri II. In late July, Mary was spirited into France, there to be raised at Henri’s court. Although a victory for English arms, Pinkie was a defeat for English policy, opening a decade of French dominance in Scotland and ensuring that the Scottish queen would become Catholic in religion and French in sympathy.

Further Reading Jordan, W. K. Edward VI: The Young King. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1968. Merriman, Marcus. The Rough Wooings: Mary Queen of Scots, 1542-1551. East Linton, Scotland: Tuckwell, 2000.