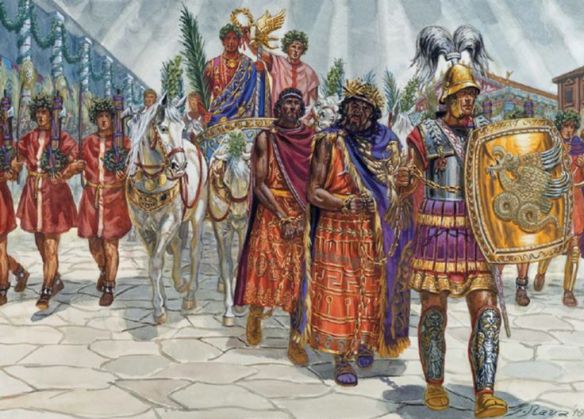

Marius´ Triumph over Jugurtha 104 BC – by Giuseppe Rava.

After the battle, Metellus went on into the richest part of Numidia, taking and torching many settlements. The final episode of the campaign was a vain attempt to capture Zama Regia and, Iugurtha having put together another army, a fierce battle in the vicinity. Then Metellus retreated, taking up winter quarters in the province of Africa, but near its border with Numidia. The Senate, meantime, prorogued his command.

The winter saw the sudden loss (through treachery) and swift recapture (through trickery) of Vaga. Then followed Metellus’ intrigue with Iugurtha’s old confidant Bomilcar. This was an attempt to put Iugurtha out of the way. It failed. After that Metellus took the field again. There was a battle in which Iugurtha was defeated. The king thereupon retired into the desert and took asylum at Thala (not identified), where his children and much of his treasure were stashed. Undaunted, Metellus marched across the sun-parched waste to Thala and captured the place, but Iugurtha slipped away with his children and most of his treasure and fled into the country of the Gaetulians. After a time he induced Bocchus, the king of Mauretania and his father-in-law, to intervene and lend a hand. Things gathered apace, and the two kings appeared in force near Cirta, which had come into Roman possession. Negotiations followed and warfare lapsed. Metellus meanwhile had received news from Rome not only that Marius, his erstwhile legate, had been elected to the consulship, but that Numidia had been assigned to him.

So far in the campaigns of 109 BC and 108 BC Metellus had repeatedly defeated his enemy (he was to gain the cognomen ‘Numidicus’ for his efforts) but had found it impossible to bring Iugurtha to heel, who remained at large in the dusty, snake infested land. Metellus had learnt to adapt his tactics to find and fight an elusive cunning foe, but Iugurtha, who was sufficiently wise not to mass his peasant levies for battle in open country, would only skirmish with the Roman forces or fight them on his own terms. With the eye of a hawk and the stealth of a wolf, he had the kind of bravery – the most effective kind – that derived from playing only when one is assured of victory. With their emphasis on fitness and fleetness, the Numidians had three societal diversions, and of Iugurtha it was said ‘he took part in the national pursuits of riding, javelin throwing and competed with other young men in running’, and ‘also devoted much time to hunting’. Of prime importance would be the ability to ride and fight well. Worked on until they became proficient in all, these athletic pursuits undoubtedly steeled the Numidians for the style of war they preferred. Armed with a handful of javelins, the Numidian horseman was the master of skirmish-type warfare, depending on baffling their opponents by their almost hallucinatory speed and bird-like agility, alternating between headlong flight and snapping-at-the-heel pursuit. Like Syphax and Masinissa before him, Iugurtha would combine the military skills he had learned while fighting under the Romans with the classical Numidian use of irregular cavalry and slippery guerrilla tactics.

Like many dynamic rulers, the wily Iugurtha appears to have been a heady blend of contradictions, at once conscientious and cutthroat, capricious and careful, cruel and compassionate. Of course, this may be a case of history being construed by the victors, but Iugurtha does seem to have been the stuff of a dark fairytale. Sallust sees the constant failure to overcome the Numidian king was in part due to Roman incompetence, with a deeper reason down to the corruption of the Roman aristocracy, an accusation we shall examine in more depth later. Somewhat naively perhaps, Sallust also represents Iugurtha both as the ‘noble savage’, immune against the corruption of Roman civilization, and as the ‘ignoble barbarian’, a paradigm of ‘Punic’ perfidy. Of those who doubted the danger of Iugurtha, Sallust saw that their attitude could only be accounted for by the sort of toleration a man extends to his pet wolf who, living in the house like a dog, only eats his neighbours’ sheep and occasionally their children too. It is easy to assert with 20:20 historical hindsight that Iugurtha was of such nature.

Next Marius in 107 BC. Despite being bitter, Metellus accepted the change in command. In fact, Marius did not bring with him any fresh ideas on how to conduct or even win a war conducted in country favouring the enemy, but he did, on the other hand, realize that the anti-insurgent war against Iugurtha required more troops on the ground. Rome, however, was suffering a long-standing manpower shortage, and its army had yet to become the formidable empire commuter in hobnailed sandals that was well used to victory over ‘barbarian’ enemies in Europe and elsewhere. But Marius took a bold step and opened the ranks to all who wished to volunteer, including the capite censi or ‘head count’, those citizens listed in the census simply as numbers because they lacked significant property. And so volunteers from the proletarii flocked to join the legions, ‘imagining that they would make a fortune out of the spoils’, and the Senate, despite assuming that he would raise the soldiers by means of the usual selection process based on the census, the dilectus, raised no protest. It was a simple step, revolutionary only in that Marius created, without realizing it, a new type of client army, bound to its commander as its patron because, as Plutarch lets on, ‘contrary to law and custom he enrolled in his army poor men with no property qualifications’.

Bred lean and resilient in the vicissitudes of survival at subsistence level, most of the men recruited undoubtedly were members of the rural population; they were considered to be better material than their urban counterparts, at best a rough undernourished lot. The desire for a life free of routine drudgery, the chance of adventure into the unknown and adrenalin-fuelled excitement all played their part, but want was the prime cause for their abandonment of civilian life. Only too grateful to have escaped the filth and fickleness of civilian life, on their demobilization at the end of a campaign they naturally looked to their general for rewards, namely a grant of land.

With that Marius, as consul in 102 BC, had to propose a land bill, which was passed for him by the unscrupulous and brilliant tribune of the people, Lucius Appuleius Saturninus. It is a common argument that from now on the armies of Rome looked to their aristocratic generals and not the oligarchic Senate, the oft-quoted example being that when Lucius Cornelius Sulla, the future dictator, got his legions to march on Rome in 88 BC. This view, however, is too pessimistic as not all soldiers would follow their general. It is probably true that throughout Rome’s history soldiers exhibited more loyalty towards a charismatic and competent commander. Therefore, what we really witness with Marius is not a change in the attitude of the soldiers but a change in the attitude of the generals. Let us, for instance, take Scipio Africanus. If he had held revolutionary ideas, he could have easily marched on Rome at the head of his victorious army after Zama. Similarly, if we return to Sulla, his soldiers did not follow him come what may as he had to convince them that he had right on his side. According to Appian, when envoys met Sulla on the road and asked him why he was marching on Rome, he replied, ‘to free it from the tyrants’. Tyranny, alongside monarchy, being an anathema to all proper Romans.

Anyway, this is another story, so let us return to Marius. He was by nature a soldier, much in his later life would show it, and he had begun his long military career as a cavalry officer, serving with distinction under Scipio Aemilianus at Numantia. Marius (much like Iugurtha) had enhanced his reputation there when he killed an enemy warrior in single combat, and in full view of his general. For a man of relatively humble origins it must have looked as if the future belonged to him. And so, some twenty-six years later, the new consul took command in Africa and began his campaign.

His army was obviously an interesting mixture of veterans and novice soldiers. Much of the army was now experienced, having been put under discipline by Metellus and led by him with constant, if moderate, success, and they had been hardened to soldiering under an African sun. This was not the case with Marius’ poor volunteers. Lacking the same stamina and steadfastness as those who had already faced the Numidians, he knew he had to break them into the African war slowly. Accordingly he exposed his soldiers, war-worn and greenhorns alike, to small fights until they were confident of themselves and the new and old hands grew easy with each other. After these preliminary preparations and opening operations, which involved largely fluid short-lived skirmishes, a spirit of teamwork henceforth prevailed among his soldiers. He was ready for a new effort against Iugurtha, who he was able to defeat in an engagement near Cirta.

However, finding that it is not so easy to end the war (with half the forces) as he had claimed, events now took an ugly turn with Marius adopting a policy of plunder and terrorism, burning fields, villages and towns and massacring the civilian population. After which, Marius conceived and planned a daring venture, a long march to surpass his predecessor’s exploit at Thala and to continue to spread terror of the Roman arms deep in the very heart of the hostile Numidian country. His goal was Capsa (Gafsa, Tunisia). Achieving a complete surprise, Marius captured the place, burnt it, massacred the adult males, sold the rest into slavery, and divided the booty among his soldiers. The destruction was complete. Sallust himself calls the treatment of Capsa a ‘violation of the usages of war’, but feebly excuses it as necessary since ‘the place was important to Iugurtha and hard for the Romans to reach’. This act of calculated cruelty certainly intimidated the Numidians into evacuating many settlements, and those few that foolishly resisted were captured by assault and razed to the ground.

The expedition to Capsa belongs late in the summer of 107 BC. Sallust is for once explicit. But then we find Marius and his army assaulting a fortress of Iugurtha perched upon a precipitous rock not far from the River Muluccha (Moulouya). Sallust describes (here and in two other places) this river as the boundary dividing the realms of Iugurtha and of Bocchus, which means that Marius is now far to the west of Cirta (about 800km as the crow flies) and not far from what is now Melilla in Spanish Morocco. However that may be, and it suggests an efficient commissariat and an endless ability to march, it was here that he came ever so close to losing the war. The long, hot march to the Muluccha was an act of folly, which only fortune corrected.40 It is curious to note that whilst Sallust sees Marius as the living embodiment of the just qualities most precious to him, he does hint that it was Marius’ quaestor, the patrician Sulla, who saved the day, the fortress being captured and with it the largest treasury of Iugurtha.

We next see Marius in retreat: even Sallust’s hero was fallible. He had to fight two engagements towards the end of his march, the first ‘more like a fight with bandits than a proper battle’, and the second a sharp encounter near Cirta, the goal of his march. Here we should point out that Marius turned out to be an able commander who, though lacking the brilliance of his nephew Caesar, understood the basic requirements for a good army were training, discipline and leadership. More a common soldier than an aristocratic general, it was in Africa that he ‘won the affection of the soldiers by showing he could live as hard as they did and endure as much’. As a tactician Marius relied mainly on surprise and always showed a reluctance to engage in a traditional, set-piece fight. He preferred to determine the time and place and would not be hurried.

The following winter and spring were a time of long parleys, the upshot being the eloquent Sulla befriending Bocchus and skilfully playing on the king’s ambitions and fears. What followed was Sulla’s spectacular desert crossing, culminating in Iugurtha’s betrayal and capture (105 BC). This bit of family treachery, proving that popular saying ‘it requires an Indian to catch an Indian’, thus terminated a conflict full of betrayals, skirmishes and sieges. Sulla had the incident engraved on his signet ring, thus provoking Marius’ jealousy. Nevertheless, Marius was the hero of the hour. He triumphed on 1 January 104 BC, entering on the same day his second consulship, and Iugurtha was publicly executed. In antiquity as today, tyrants tend to slip on the blood they have shed. The war with Iugurtha had been a rather pointless, dirty affair, a campaign of annihilation, obliteration and destruction. Yet it had made Marius’ reputation and begun Sulla’s career. Worse than that, it saw Marius and Sulla fall out over who was responsible for the successful conclusion to the hostilities, an acrimonious quarrel that was to cast a long sanguinary shadow on Rome.

The Senate, however, did not annexe Numidia, giving instead half of its territory to Bocchus, as a reward of his treachery, and half to Gauda, the weak-minded half-brother of Iugurtha. This should not be seen as evidence of the Senate’s pacifism but of its sound military and political sense. As Harris points out, there was no particular Roman reluctance to annex territory in this period, quite the contrary in fact, but it seems that Numidia was ‘an exceptionally unattractive prospect as a province’. In other words, the Senate, seeing only a wasteland good for very little except subsistence farming and grazing, but would have to be defended nonetheless, refused to annex it (there may be a lesson here for us today). Subsequently two Mauretanian kingdoms emerge, separated by the Muluccha, and at the time of Caesar’s campaign in Africa, eastern Mauretania was ruled by a second Bocchus, who, along with the Campanian condottiere, Publius Sittius, invaded Numidia (now markedly reduced in size) and captured Cirta (46 BC)..