The long-lived Masinissa was succeeded upon his death in 148 BC by his three sons Mastanabal, Gulussa and Micipsa. It should come as little surprise to find that the first two soon disappeared from the scene, leaving the last brother as the sole ruler of the kingdom. Mastanabal, however, had a son by a concubine who, because of his mother’s low status, remained a commoner. Nonetheless, he seems to have grown up with all conventionally desired princely traits: an outstanding physique, good looks, intelligence, bravery, skill-at-arms and an all-round athlete. And he was popular with the people too. The illegitimate boy was Iugurtha.

All of this presented Micipsa with some difficulties. He himself had two sons, Adherbal and Hiempsal, who he naturally wished to see succeed him. He had, however, raised Iugurtha in his royal menage with the two younger boys, making little distinction between their status. Sallust, writing years later and with the benefit of hindsight, suggests that Iugurtha’s princely qualities began to trouble the king, who saw the young man as a threat to his own beloved offspring, particularly in view of his popularity. Yet it was this popularity with the masses, continues Sallust, which protected him from his uncle, who feared rebellion if he discreetly disposed of the young man. Sallust again takes up the story, telling us that Micipsa hit upon the idea of making Iugurtha the commander of a Numidian contingent he was about to send to Iberia. Once there, the contingent would serve alongside the Roman forces under Publius Cornelius Scipio Aemilianus (the destroyer of Carthage) during what would turn out to be the closing stages of the Third Celtiberian War (143-133 BC). Overseas, and out of the public eye, there would always be a chance that the impetuous young man, who seems to have found an outlet for his personal frustrations in battlefield aggression, would be killed in action.

The habitually reckless, gallant Iugurtha not only survived but served with individualistic distinction (as did a fellow officer, one Caius Marius). It was indeed during the siege of Numantia (134-133 BC) that he was to earn Scipio Aemilianus’ approval by his soldierly qualities, but it also encouraged a Roman belief that their most dangerous opponents were men whom they themselves had taught how to fight. This deep-rooted attitude of racial superiority, coupled with a deficiency in practical application where Numidians were concerned, reveals a Roman disregard for Numidian fighting potential, a pretermission that would come back to haunt the Romans. For the time being, though, Iugurtha was to learn in Iberia the venality of many of the Romans. Flamboyant, ambitious and unscrupulous, Iugurtha became involved, or so says Sallust, with other less savoury Romans, men who saw opportunities as cronies of Iugurtha if he ever became master of Numidia. These men, Sallust continues, pointed out to Iugurtha that he was already preeminent in Numidia, while ‘at Rome money could buy anything’. Now all this was probably largely anti-senatorial carping on the part of a historian who himself fell foul of the Senate and engaged in the ever-popular Roman historical pose of denigrating the current age as one of lost virtue. However, it is certainly true that Iugurtha’s later conduct was extremely egregious.

With the destruction of Numantia, Iugurtha was mustered out. He returned home with his reputation greatly enhanced through his successful military service. On top of this, he had operated as part of the Roman army itself, and he had gained a very good understanding of the Roman character. He had even mastered Latin. He was altogether more fit to rule than his younger cousins and certainly more than willing to take the kingdom from them when the time came.

And so it was, after the death of Micipsa in 118 BC, Iugurtha put to death first one then the other of his less aggressive cousins, Hiempsal and Adherbal, and made himself master of Numidia (r. 112-106 BC). The old king had in fact adopted Iugurtha and put him on a level with his own sons three years before his death, his intention being to bequeath his realm to the three men in common, an extremely bad idea in any case, particularly in a kingdom which, despite its veneer of urbanism, was still very much tribal in its makeup. Anyway, a senatorial commission from Rome, headed by the notorious Lucius Opimius (cos. 121 BC), of hated memory for his part in achieving the murder of Caius Gracchus, had been sent to settle Numidian affairs after the murder of Hiempsal, Numidia having been divided into two warring camps. Sallust implies the delegation fell under the spell of Iugurtha, yet the outcome was to be a division of the kingdom between him and Adherbal. Whether cash actually changed hands, and the theme of venality of senators is a commonplace, the Senate as a whole could see little more in Numidia’s situation than a sanguinary and squalid succession struggle, hence the compromise.

Notwithstanding this, three years later Iugurtha began raiding Adherbal’s half of the kingdom, which bordered on the province of Africa (viz. the former territory of Carthage and roughly coextensive with modern Tunisia), ‘taking many prisoners as well as cattle and other plunder’. The hope was to provoke Adherbal into counterattacks and thus provide Iugurtha with a suitable excuse for making open war upon him. But Adherbal would not be provoked. He put his faith in Roman power and sent envoys to Rome. He also sent envoys to remonstrate with his cousin, but to no effect. Iugurtha took this parleying as a sign of weakness and began war in earnest. With little or no option, Adherbal raised forces and met Iugurtha outside his royal capital, the hilltop fortress of Cirta. The two armies approached each other but as it was late in the day did not engage. During the small hours of the following morning, however, while it was still fairly dark, Iugurtha attacked Adherbal’s camp and routed his sleepy army completely. Adherbal escaped in the confusion with a small mounted force and fled to Cirta, where he was saved from capture by resident Italians, traders (negotiatores Italici) to be exact. They obstructed the pursuit from the walls, probably with missile weapons, and had it not been for this, ‘a single day would have seen the beginning and the end of the war between the two kings’.

Iugurtha thus settled into a siege and assaulted the fortress, which squatted upon a ravine-girt promontory, with mantlet, tower and ram. This approach showed his army was more technologically sophisticated than might be expected from an out-of-the-way desert kingdom. Nonetheless, the siege was to drag on for some five months, during which time a pantomime of negotiations were conducted between Iugurtha and Rome, the king blatantly ignoring instructions from two Roman missions to disarm. Eventually, fearing for their own safety, the Italians defending Cirta prevailed upon Adherbal to surrender his capital on the terms that he would be spared and that the Senate would then sort the mess out. Adherbal was rightly dubious, but submitted to the Italians’ pressure. Adherbal’s assessment of the situation was more astute than that of the Italians. Upon surrender, Iugurtha tortured Adherbal to death and slaughtered all Italians that were found bearing arms. With their massacre Rome declared war.

In spite of Iugurtha’s lavish use of bribery (according to Sallust – how fair this accusation is we cannot say, but it is probably exaggerated), the Senate decided to crush him. After two unsuccessful attempts (111-110 BC), it despatched the quixotic but capable Quintus Caecilius Metellus against him. The Caecilii Metelli were the most prominent family in Rome at this time (six consulates in fifteen years), having risen past the Cornelli Scipiones, who had held this position since the war with Hannibal. On his arrival in Africa, Metellus had to knock the army into proper shape; the troops were in poor condition after the command of the two Postumii Albini, who had allowed the campaigning army to rot and decay. They had abandoned military routine to spend weeks in ill-disciplined idleness, not bothering to fortify or lay out their camp as per regulations, and shifting it only when forced to by lack of locally available forage or because the stench of their own waste became unbearable. Soldiers and camp followers marauded and plundered at will. This was the army in Africa when Metellus assumed command in the summer of 109 BC.

Metellus’ response was a traditional one, namely to put the men back under the tight, all-embracing discipline that the Roman army was famed for. Traders, sutlers and other unscrupulous parasites were expelled, and soldiers forbidden to buy food; many had been in the habit of selling their rations of grain to purchase ready-baked civilian bread rather than eating the coarse camp bread they had to prepare and cook themselves, which was often a recipe for gastronomic disaster. Ordinary ranks were barred from keeping their own servants or pack animals. Metellus ordered gruelling daily drills to reintroduce the men swiftly to the intricacies of military life, as well as to improve battle skill and endurance. From now on the army broke camp every morning, and marched fully equipped to a new position where it constructed a marching camp as if in hostile territory. ‘By these methods he was able to prevent breaches of discipline, and without having to inflict many punishments he soon restored the army’s morale’.

Obviously no martinet, Metellus understood that when a commander leads his soldiers into battle, they must follow without hesitation. He works hard to earn this loyalty by knowing and caring for his men. He is what we would call a good commander. With natural inquisitiveness about how people function, the good commander connects to his soldiers in an intimate and personal way. Loyalty above all is based on appreciation. It develops when people appreciate what they are involved in and when appreciation is expressed for them. The good commander earns the loyalty of the soldiers by first genuinely expressing loyalty to them in even the smallest gestures. He does not miss the opportunity to win someone’s trust and never gives up on anyone. In this way he creates a unified entity where before was an assembly of individuals and gains an army that follows him through extreme conditions and conflict. Metellus was of this stamp.

When the commander does not command, the army cannot obey. All becomes confusion. Yet united in profound kinship with their commander, the soldiers respond with uncompromising loyalty. They will obey every order. They will accompany him far and wide, into grave danger, into death. When soldiers face death, the structures of military life become irrelevant. At the same time, creating certainty and fostering commitment are paramount because when the good commander exudes confidence and his commands and orders are clear and simple, when doubts have no chance to arise, the men will be confident and assured in their actions. Enthusiastic, unquestioned commitment will dispel doubt, carry men through battle and rob the enemy of his spirit, thus causing fear, consternation and confusion in his ranks. Orders must never be issued lightly, nor should they be rescinded; otherwise, they lose their power and impact. The fearsomeness of a commander in the midst of battle depends on the acceptance and execution of his orders and this execution depends on the fear, respect, and willing allegiance of the men. In particular, their respect is hard to win and could be snatched away in a single moment of cowardice or indecision. ‘You should know that while success wins for commanders the goodwill of their men,’ the Caesarian legate Curio explains to his war council, ‘failure earns their hatred’. Clearly, the most extensive efforts must be taken to preserve this interrelationship because once a crack such as doubt appears, the collapse of authority is imminent. Paradoxically, a man is not born a commander. He must become one through experience.

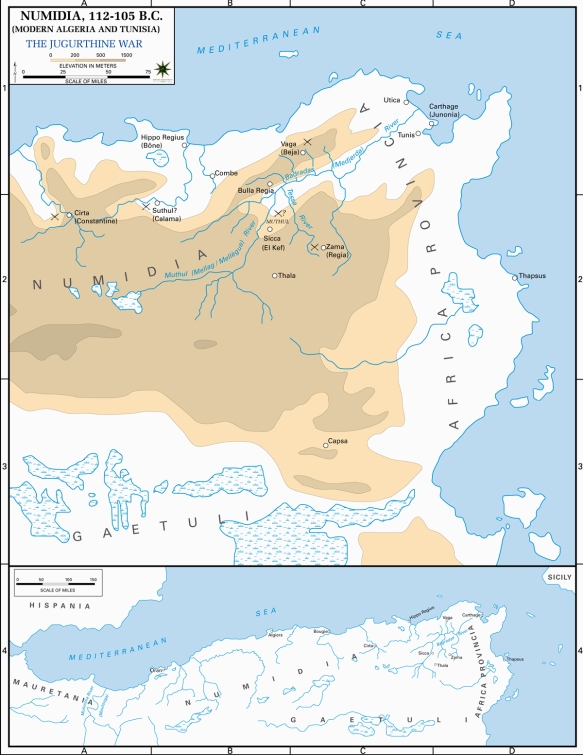

But back to Metellus. Invading Numidia, he occupied Vaga (Beja, Tunisia). Marching southwestwards, he soon had to fight a major battle. The site of this confused whirling fight was beside the Muthul (Oued Mellag), a tributary on the right bank of the Bagradas, not far to the north of Sicca, which city then came over to the Romans.

THE BATTLE OF THE MUTHUL RIVER, 109 BC

Having left a small detachment in Vaga to guard a supply dump he had established there and to protect its resident Italians, Metellus pulled out. In the meantime, Iugurtha assembled his forces, horsemen of course, foot levies and elephants. The latter, forty-four in number, along with part of the infantry, he placed under his old friend Bomilcar. He then got his troops ahead of the Roman column and decided to fight among the barren hills near the Muthul River. The king placed his troops in a thin line along the top of a hill overlooking the route he knew the column would pass along. He hid his men as best he could among the scrub trees on the hill and concealed his banners and flags so as not to advertise his whereabouts. He then waited for the moment of ambush.

Descending from a height, the Roman column was slowly uncoiling and heading towards the Muthul when Metellus spotted the ambush again against the browns, greys and greens of the landscape. He immediately halted the column and turned to face the nearby scrubby hill now bristling with glistening, war-caparisoned warriors, thereby putting his army into battle formation. He bolstered the right wing, which was closest to the hostiles above, with three more lines of maniples and distributed archers and slingers between them. He then divided his cavalry and set them on the wings. Iugurtha did not attack at once, probably he had to rethink his tactics and reorder his men accordingly, and Metellus, concerned that his men might be worn down by thirst, sent one of his two legates, Publius Rutilius Rufus, with a body of horse and some lightly-equipped cohorts down into the plain to establish a camp besides the Muthul.16 As this detachment passed below the Numidians, Bomilcar proceeded after it with his infantry and elephants.

Then, with quiet steadiness, the Roman army faced left and became a column once more. With Metellus and cavalry acting as vanguard, and his other legate, Caius Marius, and more cavalry acting as rearguard, the army descended slowly but surely into the plain below. As the rear of the column reached level ground, Iugurtha sent some 2,000 men to occupy the route through which they had passed, apparently with the intention to trap them in the plain, which, excluding the herders subsisting along the Muthul, was deserted owing to the lack of water.

Iugurtha then began to attack the column’s flanks with his horsemen, which dashed hither and thither casting javelins. When pursued they simply melted away, fleeing in all directions and trying to cut off any isolated Roman cavalrymen they could find. Sallust says that these shoot-and-scoot assaults disordered all the ranks, which suggests the column was caught off-guard before it could properly deploy into battle formation. Nonetheless, there was a good deal of hot fighting at close quarters, and a final successful charge by, as Sallust makes plain, ‘four legionary cohorts’ towards some of the Numidian infantry that had pulled back upon high ground put an end to the engagement in this quarter. Most of these Numidians slipped silently away into the surrounding bush, and only their dead and badly wounded were left with the Romans.

In the meantime, Rutilius and his command had found a suitable camping site, had marked out a camp and begun to entrench, when a great cloud of dust appeared before them. The Romans guessed at first that it was merely dust that had been carried up by the wind, the plain was broken country covered with thick scrub, and it was difficult to see that it was really a sign of the approaching enemy. There was no sense of urgency yet. The Romans continued with their labour. But when they saw the dust cloud was not dispersing but getting nearer, they grabbed their arms and, pouncing upon the Numidians, the rest was quickly over. To return to Sallust’s account, ‘The Numidians stood their ground only as long as they thought they could rely on the elephants for protection’. They took to their heels, however, when the Romans slaughtered all but four of the beasts, which had got themselves entangled in branches of trees. The sudden African fall of night meant that the cavalry of the divided Roman force met in the dark. Luckily they recognized each other, which thus enabled the fagged column to reach the camp. All told, Metellus had just managed to win a confused and hard-fought and expensive victory.

Apart from the forty-four elephants, Sallust gives no figures for either side.19 In fact, the historian eschews any estimate of numbers (along with chronology) in the Bellum Iugurthine War, even on the Roman side. Metellus presumably had a standard consular army of two legiones and two alae, say some 20,000 men. It may have been smaller; he must have left troops to garrison various points, such as Vaga, and also to protect the province of Africa, but then he had brought some additional manpower with him when he took up his command, so 20,000 men seems a good guess. As for Iugurtha, it is impossible to say.

Iugurtha got away, and thereafter Metellus, wary of heavy losses in pitched battles against an unencumbered and highly mobile enemy, would settle down to a piecemeal conquest. Nonetheless, Metellus would fail to bring the war to a conclusion; the problem was physically capturing Iugurtha. Metellus, therefore, resorted to bribery coupled with a policy of reducing the urban communities in Numidia so as to deprive Iugurtha logistically. As we shall see, Marius was to employ the same strategy against Iugurtha, thus we should be wary of criticism of Metellus’ conduct in Africa. That said, there was a senatorial tradition glorifying Metellus, asserting that he had broken the back of Iugurtha’s resistance when for reasons of (unjust) home politics he was replaced by Marius.