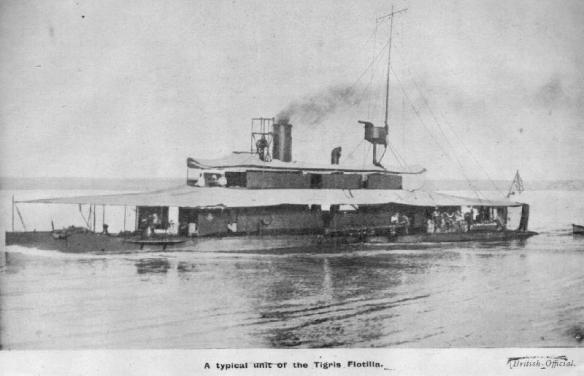

The gunboat HMS Firefly, one of the ‘Fly Class’ gunboats used against the insurgents.

Once more the commanding officer scanned the derailed armoured train and the surrounding desert while he and his fellow officers strained their ears for any sound of firing. However, it now seemed certain that all resistance had ended and, having consulted with his staff, Major Hay decided there was nothing more he could do for the men on the armoured train. By now, they were either dead or taken prisoner.

Tragically, this was not the case. Later reports from a handful of sowars who escaped the train but were later captured by the insurgents told a story of a heroic long-drawn-out resistance on the part of the British officers and Indian troopers who were unable to get away. Lieutenant Russell, Captain Pigeon and some of the remaining troops had barricaded themselves into one of the loopholed armoured wagons, from where they kept up an intense fire upon their assailants. The rebels then poured oil onto the tracks beneath the truck and eventually set it alight. How long this process took will never be known, but at some point the survivors were driven out by the smoke and flames and most were shot down as they tried to escape.

It seems the garrison at Main Camp might have been able to save them had they made the attempt, but Major Hay’s predicament, in the face of what appeared to be clear evidence that the train’s occupants had been killed at an early stage in the fighting, was understandable. It remains a mystery why no sound of the continuing fighting reached the British officers in Main Camp, but Haldane himself would later observe that ‘the atmospheric conditions in Mesopotamia are fruitful causes of deception’ and that the summer dust and wind could easily have affected both sight and sound. He also acknowledged that any attempt to make a sally from Main Camp in adequate numbers would certainly have put the latter at serious risk.

Nevertheless, this had been the most serious defeat so far for the Samawa garrison. Fifty men and officers had been killed in the fighting and another 12-pounder gun (the one on the derailed armoured train) had been lost to the enemy. And as the British withdrew into their narrow defensive position along the river bank, the insurgents began to encircle them with a network of trenches while at the same time large groups of rebels took up positions on the left bank of the Euphrates directly opposite Main Camp, from where they began to enfilade its defenders.

As the September days passed, the defenders of Samawa were put on half rations. Meanwhile the enemy trenches crept closer and closer to the British barbed wire and one of the captured 12-pounder guns began a sporadic bombardment of the British trenches around Supply Camp. Indeed, the fact that they were now coming under artillery fire convinced the defenders that they were facing Turkish troops who had arrived to support the Arabs. This belief was reinforced when the gun removed from the armoured train which had been derailed at Khidhr was also brought into service. Moreover, the extent to which the fighting was increasingly taking on the characteristics of regular warfare was highlighted by the fact that the insurgents’ trenches were now fortified with sandbagged positions from which they could snipe at the British defenders and from which the rebels launched attacks with hand grenades. For those who had fought in the Great War the situation seemed almost on a par with the Western Front.

Now, believing the British to be unable to keep up their resistance for much longer, the insurgent commander, Sayyid Hadi al-Mgutar, sent an emissary to Major Hay under a white flag. The British commander was informed that his position was surrounded by over 20,000 troops and that the insurgents were aware that the defenders were fast running out of food and ammunition. However, they would be offered generous terms. If they surrendered, each man of the garrison would be allowed to keep his weapon and the garrison would be allowed to march to the nearest British position.

However, throughout the siege, Major Hay had been able to maintain radio contact with Baghdad and by now he was aware that a large relief column was being assembled at Nasiriyya. Although the latter was sixty miles away and it might take three or four weeks to reach them, Hay believed he had just enough food and ammunition to hold out. Hadi al-Mgutar’s generous terms were therefore summarily rejected.

Meanwhile the insurgents’ attention focused on the stricken gunboat, HMS Greenfly, stuck firmly in the mud a few miles south of Samawa. It was now that the British decision to leave the crew and military escort on board until further rescue attempts could be made tragically unravelled. The men of the Greenfly were beginning to run out of food but the gunboat had not been left totally unaided. Attempts were made by the Royal Air Force to drop supplies to the ship but so far three-quarters of the provisions had fallen short, into the river. However, on 22 September a Bristol Fighter, crewed by Flying Officer Bockett-Pugh and Flying Officer Macdonald, attempted to drop their food parcels as accurately as possible but were shot down and their aircraft fell into the river about one mile above Khidhr. Both crewmen escaped the wrecked plane but on clambering up the river bank, one of the officers was immediately shot and killed by tribesmen of the Jawabir, a section of the Bani Huchaym. The other officer apparently attempted to negotiate with the tribesmen and promised a large reward if he was given safe conduct to the Greenfly, but sometime later the headman of a local village arrived on the scene and shot the remaining officer. The bodies of both aviators were subsequently mutilated. After this incident no further attempts were made to supply the Greenfly by air.

By 30 September the situation on board the ship was getting desperate but the Greenfly’s captain, Alfred Hedger, managed to get a message out to his commanding officer at Nasiriyya via a friendly local sheikh who had been passing occasional messages between the gunboat and Nasiriyya since it had become stranded.

Political Officer, Nasiriyya

Sir, I am in receipt of your communication dated 20th instant. You will no doubt have seen my letter to the G.O.C. which was sent to the G.O.C. by Sheikh Wannas of El Bab and left yesterday.

Food is the great question on board; but if your arrangements are successful, I expect we shall be able to hang on. The condition of the crew is really very good considering the very severe shortage of rations that we have all experienced. Our spirits are still ‘up’ altho’ at times we have felt very depressed. To get your letter and to know that things are happening helps us all very much indeed. I have lost one Indian and I have one B.O.R. [British other ranks] severely wounded; besides these casualties I have one Indian wounded and 3 or 4 men sick owing to weakness – lack of food … There are 31 Indians, and you’ll know the number of B.O.R.s on board. Give us rations and we will have the heart and spirit to stick it out to the end … Thanking you for your cheerful letter and again assuring you of our all performing our duties to the best of our ability.

I have the honour to be, sir, your obedient servant,

Alfred C. Hedger.

It was to be the last communication from the Greenfly. Precisely what happened to the crew and escort will never be known. Only one body – that of a European – was ever found and none of the crew or escort were ever seen again. It appears that sometime around 3 October, the Indian troops may have mutinied, killed Captain Hedger and the other British and then handed the ship over to the insurgents. The rebels then boarded the ship, stripped it of everything of use including the 12-pounder gun and set it alight. Such was the conclusion of the court of inquiry held some months later, although Haldane would later comment that ‘no absolute proof of this has been obtained.’

At Samawa, however, the Indian troops remained loyal. As the siege continued, Arab insurgents who knew a few words of Hindustani began to creep up to the British trenches during the night calling out to the sepoys to abandon the British and come over to their side. Appeals were made, in particular, to the religious sentiments of the Muslim Indian troops, but there was no response. Later, their British officers expressed pride in the loyalty of their ‘fighting sons of India’, one of whom awarded them what was apparently intended to be the ultimate accolade: ‘Black they were, but white inside.’

Meanwhile, Haldane was massing troops at Nasiriyya in preparation for his relief operation. By the end of September he had put together a powerful column composed mainly of the troops that had recently arrived from India. It consisted of the 1st Battalion King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry, three battalions of the Gurkha Rifles, a battalion of the 23rd Sikhs and two squadrons of the 10th Lancers. The column was supported by a Royal Field Artillery battery, a howitzer battery and two and a half sections of a machine-gun battalion together with a company of sappers, medical corps and transport units. By now Haldane had also acquired another squadron of RAF fighter bombers – the 55th Squadron equipped with the newer DH9As which had arrived at Baghdad West airfield on 23 September.

But while he was deeply engaged in these plans for a major counter-offensive, there was another matter the consideration of which was causing General Haldane frequently sleepless nights: responsibility for the Manchester Column debacle. It was all the fault of Major General Leslie; at least, that was how Haldane saw the matter. From time to time little episodes of self-doubt troubled him. Was it just possible that there had been some ambiguity in his instructions to Leslie when he had telephoned to ask permission for the column to advance so ill-advisedly into enemy territory? Or could Brigadier Stewart, who took and answered the call, have somehow garbled those instructions? However, in the end, the general always managed to suppress such thoughts, returning, with absolute conviction, to the opinion that it was Leslie who was to blame; but would others see it that way? In the end, he decided that the only way to deal with the matter was to confront Leslie openly with his ‘serious error of judgement’ and if he still refused to accept his responsibility, then he could always remove him from command of the 17th Division – he had the power to do that, after all.

For his part, Major General Leslie was becoming aware of Haldane’s antipathy towards him and that he might be preparing some kind of disciplinary move against him. Writing to his wife on 28 August, he told her, ‘I gather from General W. who had a long interview with the Chief that I am not in favour there. I am said to be too parochial in my views and think that there is nothing to do but clear the Hilla area.’

And to Wilson, on 17 September, he complained, ‘The 17th Division is in great disfavour and cannot do right. I have little hope of many of my recommendations bearing fruit,’ adding that the Manchester Column incident was ‘at the bottom of my troubles’. The fact that Leslie was now communicating directly with the acting civil commissioner speaks volumes for the acrimony between himself and Haldane, since Wilson’s own relations with the commander-in-chief had long since deteriorated to the point where they were now barely on speaking terms. In his letter to Wilson of the 17th Leslie poured out his own bitter feelings about the way Haldane’s strategy had effectively condemned some of Wilson’s men to a lonely and isolated death:

Much worse, I think than the Manchester Column was the abandonment to their fate of Ba’quba [Shahraban] and its officials by a force of British cavalry, guns and infantry with station under a mile away, because it was considered essential to save Baghdad from capture. This took place on the 12th of August. I heard of it only on the 2nd September.

Indeed, Haldane was now deliberately leaving Leslie ‘out of the loop’ of military communications, dealing over his head directly with brigade commanders like Coningham; and commenting on Haldane’s failure to inform him immediately of the Shahraban incident and other matters, Leslie tells Wilson, ‘It is curious that I, who would have to carry on for the GOC-in-chief if anything happened to him, should have been left in such complete ignorance,’ before thanking him for information on ‘important military happenings’ of which he had been kept in the dark. And he ends the letter by telling Wilson, ‘I am very sorry indeed that you are going,’ it now having been confirmed that Sir Percy Cox would be returning to Iraq to replace Wilson on 4 October with the new title of ‘high commissioner’.

By 1 October all was ready and the Samawa relief column – christened SAMCOL according to the practice of the day – marched up the Euphrates to Ur, where it was joined by one and a half companies of the 114th Mahrattas. In addition to the troops, the column was accompanied by two supply trains each carrying 30,000 gallons of water and all the other necessary provisions, an armoured train with a 12-pounder gun, machine guns and a searchlight, and a blockhouse train with materials sufficient for the construction of ten blockhouses to defend the lines of communication. In this southern region of Iraq the heat was still very oppressive and the march to Ur was particularly trying for the 574 officers and men of the King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry, who were the only British soldiers in the column, except for the gunners. Although, as usual, ‘water discipline’ was the rule, the officers and NCOs of the light infantry battalion had great difficulty in enforcing it.

By 6 October the column, commanded by Brigadier Coningham, had reached Khidhr, where a strong body of insurgents was attacked and driven off by the Gurkhas and Sikhs. On 8 October the column reached a point near to the river bank where the Greenfly had been destroyed. As yet there was no suspicion of the events which were later discovered to have taken place, although a friendly sheikh offered the information that the British had been murdered while the Indians had been taken prisoner. In reprisal, as they advanced, all the Arab villages the column encountered were burned. By 12 October the column was just four and a half miles short of Samawa.

The insurgents’ commander, Sayyid Hadi al-Mgutar, had no choice but to try to block Coningham’s advance. He gathered around 7,000 tribesmen, of which about 3,000 were armed with modern rifles, and deployed them in a position straddling the railway line, stretching through palm groves and walled enclosures. It was a strong position but at 8.00 a.m. on 13 October, Coningham launched an all-out attack supported by four aircraft which bombed and machine-gunned the defenders. By 1.30 p.m. the British troops nearest the river reported that large numbers of insurgents were still holding out and blocking their advance. Since the troops were now some miles ahead of the railway supply trains, which were held up, rebuilding the railway line, Coningham called a halt to the attack. However, the following morning it was discovered that the rebel army had abandoned its positions both in front of and surrounding Samawa. By noon the British were in possession of the town, whose entire population had fled except for twenty-five Arabs and the same number of Jews.

Although as yet it was by no means clear to either side, the relief of Samawa was the turning point in the insurrection. Although the fighting would drag on for another three and a half months, it was the beginning of the end. As both sides anticipated, the failure of the rebels to capture the British position at Samawa convinced the Muntafiq tribes that they should remain on the sidelines of the struggle and, as many of the insurgents themselves reluctantly recognised, without the Muntafiq they stood little chance of victory.

Mid-October 1920 was also ‘the beginning of the end’ for Leslie’s command of the 17th Division. Haldane, continuing to brood on the shambles which had led to the Manchester Column disaster, had finally decided to act. On 16 October Leslie received an ‘official’ communication from GHQ objecting to the statement in one of Leslie’s dispatches to the effect that the Manchester Column had set out from Hilla ‘with the approval of the C-in-C’. It was stated in the GHQ ‘official’ that the C-in-C ‘knew nothing about the move until it was made’. In response, a furious Leslie informed Brigadier Stewart, Haldane’s chief of the general staff, that ‘unless his “official” was cancelled I would reply to it officially’.

Stewart promptly telegrammed Leslie cancelling the ‘official’. But Haldane had no intention of backing down: a few days later he relieved Leslie of his command, informing the War Office that he had ’lost confidence in Major General Leslie’.