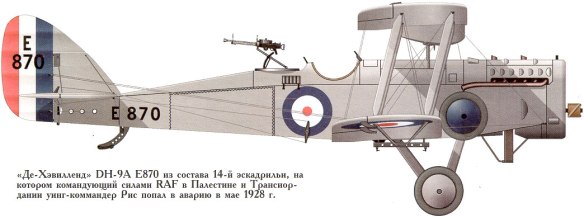

The more modern DH9A which largely replaced the elderly RE8 towards the end of the uprising.

The middle Euphrates region, epicentre of the 1920 revolution, showing the principal tribal area.

The sun, whose delightful rays gently bathed the British war minister as he stretched out in a deckchair in one of the Duke of Westminster’s secluded, box-fringed gardens, presented a fearsomely different aspect 2,400 miles to the south-east and 15 degrees latitude below the Duke’s Gascon landscaping. As the 574 officers and men of the 1st Battalion, King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry clambered down onto the dock at Basra on 8 September 1920, after a trying journey up the Gulf from India, the heat fell upon them like some dreadful beast of prey. While waiting for re-embarkation at Bombay they had become acclimatised to an Asian summer to a limited extent; but the 120°f, accompanied by a fiery desert wind which met them in Basra and lasted for the full nine days they were stationed at the neighbouring military camp, was too much for many of the young men from the industrial and mining towns of Wakefield, Doncaster and Pontefract and heatstroke casualties mounted rapidly.

The battalion had been rushed out to Iraq from India before it had been properly equipped, so the unit was compelled to suffer the heat and flies of Makina Camp while Major A. Barker MC, the quartermaster, did his best to round up the missing stores and equipment. Eventually, on 17 September, the battalion was loaded onto a train and transported to Nasiriyya on the Euphrates, where they were brigaded in the 74th Brigade with three Indian infantry battalions – the 2nd Battalion 7th Rajputs, the 1st Battalion 15th Sikhs and the 3rd Battalion 123rd (Outram’s) Rifles – reinforcements which had been rushed to Iraq during the preceding month.

These were but a small proportion of the reinforcements which Churchill had decided to use against the rebels. On 17 August a Pioneer battalion (1/12th Pioneers) had disembarked at Basra together with the 2nd Battalion 96th Infantry, in total 1,518 officers and men, destined to be deployed on the Tigris defending the Kut-to-Baghdad lines of communication. The next day the 3rd Battalion 23rd Sikh Infantry arrived and were ordered to Nasiriyya, followed, two days later, by the 2nd Battalion 117th Mahrattas. Five days later the 2nd Battalion 116th Mahrattas arrived and were dispatched by train to Baghdad and the following day the 2nd Battalion 89th Punjabis disembarked and were also sent north to defend the capital and its communications with Kut. On the last day of August, these were followed by the 3rd Battalion 70th Burmans who were retained in reserve at Basra.

Ten days after the arrival of the King’s Own, three more Indian infantry battalions arrived at Basra – the 2nd Battalion 153rd Rifles, the 63rd Palamacottahs and the 3rd Battalion 124th Baluchis; the Baluchis were retained at Basra and the other two battalions sent on to Nasiriyya. They were followed, between 23 and 28 September, by the arrival of four battalions of Gurkhas, totalling 2,547 officers and men; and finally, another Indian unit, the Kapurthala Infantry.

Although two more British units, the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry and the 2nd Battalion East Yorkshire Regiment, also arrived in Iraq at the end of September, of the 15,434 reinforcements which Haldane received between 6 August and 29 September, only 16.8 per cent were British. Haldane’s ‘British’ Army was no less overwhelmingly ‘Indian’ than when he had arrived. Nevertheless, Haldane now considered he had sufficient strength to move decisively against the Arabs.

With no knowledge of these massive British reinforcements, the inhabitants of the liberated areas remained jubilant. Over the previous three months, the insurgents had rejoiced over a series of magnificent victories over the infidel occupation forces – how their heroic tribal armies had inflicted one defeat after another upon the British and their wretched Indian slave-soldiers, driving them from virtually every town and village on the Middle and Lower Euphrates; of the remainder, British garrisons at Samawa and Kufa were besieged and Hilla was under sporadic attack. On the Diyala, north-east of Baghdad, the Arabs had isolated the British from their troops in Persia; to the west of Baghdad, the insurgent Zauba‘ tribes held sway and had cut off the British outposts at Falluja and Ramadi from the capital; meanwhile, on the Tigris north of Baghdad, Muhammad al-Sadr, having escaped the attempt to capture him, was personally rallying the tribes in an attempt to seize the old walled city of Samarra. Only the death of the revered Grand Mujtahid Mirza Muhammad Taqi Shirazi in August had somewhat dimmed the insurgents’ general mood of exultation.

But among the leadership of the uprising the mood may have been more subdued. In particular, the new Grand Mujtahid, Sheikh al-Shari‘a Isbahani, must have been uneasy with the progress of the rebellion. Emissaries from the holy cities had repeatedly been sent out to the tribes on the Central and Lower Tigris – to the Bani Rabia‘, the Bani Lam and the Al Bu Muhammad – but to no avail. Their sheikhs, now well paid with British subsidies and supported by gangs of heavily armed retainers, dominated their lesser sheikhs and tribesmen and had snuffed out any incipient movements of support for the insurrection. And as yet, there had been no real show of support from the great Muntafiq confederation whose sway extended over the Lower Euphrates and up the Gharraf and Hai rivers.

Like his predecessor, Isbahani was of Persian birth and like Shirazi he was a man of great learning, fluent in classical Arabic; he, too, had taken a strongly constitutionalist position in the great Shi‘i religious and political debates at the time of the prewar Persian revolution. But there the similarity ended. The seventy-one-year-old cleric had none of the pacifist tendencies that had made his predecessor initially reluctant to acknowledge the justice and necessity for armed rebellion. Isbahani had long been an advocate of armed resistance to European encroachment into the Muslim world. In 1914 he had been one of the most active mujtahidin in rallying the tribes for the jihad against the British invasion and the hard experience of defeat had done nothing to soften his bitter hostility towards the British. Moreover, unlike most of the other clergy of Najaf and Karbela’, Isbahani had a shrewd understanding of military strategy and was particularly conscious of two prerequisites for the insurgency’s victory – the utmost unity among the tribes, and the need to counterbalance the occupiers’ preponderance in heavy weaponry by seeking every opportunity to capture British artillery pieces and machine guns. He was also a good judge of subordinates and had already sent one of his most able commanders, Sayyid Hadi al-Mgutar, another veteran of the 1915 jihad, to take charge of the tribal forces besieging the British base outside the rebel-held town of Samawa.

In itself, the base was not a great military prize. It had a battalionsized garrison of British-officered Indian troops, an armoured train and some machine guns and mortars. The real significance of Samawa, however – as Isbahani fully understood – was the impact its capture would have upon the Muntafiq, who could easily add 20,000 armed men to the insurgent forces if they could be persuaded to rally to the cause. And if the Muntafiq joined the insurgency, then some, at least, of the Tigris tribes might do likewise.

Isbahani must also have been puzzled, as well as worried, about the inactivity of the Muntafiq. True, the one man who might have rallied the Muntafiq in support of the insurgency was no longer in Iraq. Ajaimi Sa‘dun, the paramount chief of the Muntafiq tribes, who had been one of the key leaders in the 1914–15 jihad against the British invaders, had fled the country at the end of the war and was now with Mustafa Kemal’s Turkish Army of Independence, confronting the Allied troops and Greek invaders occupying parts of Western Turkey; and there were other Muntafiq sheikhs, like Khayyun al-‘Ubayd who had fought hard against the British even after the defeat of the jihad at Shu’ayba; and after the end of the war, Sheikh Badr al-Rumayidh of the Albu Salih and paramount chief of the great Bani Malik tribe, who had also fought at Shu’ayba, refused to offer his submission to the British and held out until October, 1919 when the sixty-five-year-old leader, harassed by British columns, finally surrendered and was sent into exile in Muhammara.

What Isbahani apparently didn’t know was that, in the region of the Muntafiq, the British had an exceptionally brave and able PO – the twenty-eight-year-old Captain Bertram Thomas. He had fought in Belgium in 1914 before being posted to the Somerset Light Infantry, where he had taken part in General Maude’s successful advance to Baghdad. Thomas had then joined the Political Service and, after originally being posted as APO at Suq al-Shuyukh on the Lower Euphrates, in late 1918 he was sent to Shatra on the Lower Gharraf River, perhaps the most isolated and potentially hostile post in the whole Muntafiq-dominated region.

Although Thomas had carried out all the usual functions of a PO, including tax collection and mobilising forced labour, it seems he had carried out these duties – insofar as this was possible – with considerable tact and sensitivity. He was no Leachman or Daly and had never called in aircraft to bomb recalcitrant villages. Above all, he seems to have had the knack of making friends with the local sheikhs so that when, in August 1920, it was decided that it was no longer sensible to leave him isolated and exposed at Shatra and he was withdrawn on a gunboat, he had the assurance of those sheikhs that the region would remain quiet. Nevertheless, as Thomas was forced to admit in a report submitted at the beginning of the uprising, the Lower Gharraf would only remain peaceful so long as its inhabitants could see the British defeating the insurgents. If the tide turned decisively against them – in particular at Samawa – the Muntafiq of the Gharraf would doubtless join the uprising, and with them, the remainder of the Muntafiq tribes.

This was precisely General Haldane’s concern. He had originally considered withdrawing from the British base outside Samawa, as he had done at Rumaytha and Diwaniyya. Had he done so, it is more than likely that the Muntafiq would have seen this as a British defeat and joined the uprising. As it happened, by the time he had firmly decided on withdrawal, he was unable to implement it: the base was completely surrounded and under almost daily attack.

By the time the net closed around the Samawa base in mid-August, its garrison consisted of 625 officers and men, the equivalent of a battalion, albeit one made up of three different units – two and a half companies of the 1st Battalion 114th Mahrattas, two companies of the 2nd Battalion 125th Napier’s Rifles, and fifty men of the 10th Lancers. The officer commanding was Major A.S. Hay of the 31st Lancers.

The British-officered Indian troops were actually deployed in four separate camps. The main camp was situated roughly a mile north-north-west of Samawa town in a great bend in the Euphrates, accessible to river supplies and gunboat support. A quarter of a mile further west, also on the river, there was another position, known as the ‘supply camp’. About a mile west of the supply camp, yet another small post defended the Barbutti Bridge across the river. The supply camp and the main camp were linked by trenches and barbed wire but the Barbutti position was not. Moreover, as the defence perimeter was reduced in order to build these defences, it became impossible for aircraft to land or take off, eliminating one source of supply.

The weakest part of the British defence network lay a few hundred yards south of Samawa town: here, a long way from the river and more or less cut off from the rest of the garrison, the British had built a railway station through which ran the Basra–Baghdad line. In order to maintain rail supplies from Khidhr station, seventeen miles to the south, it had to be defended and in August 1920 it was held by a hundred men of Napier’s Rifles and fifty troopers of the 10th Lancers, under the overall command of Lieutenant Oswald Russell, also of the 10th Lancers. Two other British officers were at this position, known as Station Camp – Second Lieutenant H.V. Fleming, commanding the Napier’s Rifles and a medical officer, Captain J. W. Pigeon. By chance, an armoured train with a 12-pounder gun was also parked at Station Camp.

Although the British were by no means demoralised, the defence of Samawa had commenced with a number of setbacks, the first being the foundering of the gunboat HMS Greenfly, now stranded with its crew a few miles downriver. On 12 August the railway line between Samawa and Khidhr had been torn up by rebel tribesmen and it was reported to Haldane that a force of around 2,500 insurgents was marching on Khidhr itself. Since the latter was defended by only three troops of levies and a handful of Gurkha Rifles, the general decided that it would have to be abandoned immediately, leaving Samawa isolated, except by river. But even this manoeuvre ended badly.

There were three trains at Khidhr, two of them armoured. The plan was to load all the men and horses at Khidhr into the three trains and transport them south to Ur Junction with the two armoured trains following the leading (unarmoured) train at five-minute intervals. However, as the evacuation procedure began, the rebels began to close in and their attacks considerably hindered the loading of the horses and men. Then, at around 3.30 p.m., as the three trains were pulling away from the station under intense fire, the second train collided with the rear of the first, becoming derailed and blocking the line for the third armoured train. The first train managed to move off and the officer in charge sent orders that the seventeen men of the Gurkha Rifles who were occupying the train nearest to Khidhr should abandon it and jump aboard the one which was escaping. For some reason this message never reached the Gurkhas and they remained behind. All of them were subsequently killed. Tragic though this was, it was not so serious a loss as the 12-pounder gun which had been mounted on the rear armoured train. This was removed by the insurgents and later carried to Samawa, where the small number of former Ottoman army officers and NCOs readied it to bombard the British positions.

Since the only supply route to Samawa now lay on the river, and by the last week in August the defenders were running short of food and ammunition, a supply convoy made up of three Fly-class gunboats and two merchant vessels towing barges was assembled at Nasiriyya and on 26 August it began to steam upriver. The convoy also carried forty-five men of the 2nd Battalion 123rd Rifles as reinforcements.

As it approached Khidhr the flotilla came under heavy rifle fire and one of the merchant vessels in the rear, S9, appeared to be in difficulties. The gunboat astern of it signalled, asking whether assistance was required, but when it was replied that all was well, it overtook S9 and joined the rest of the convoy which, by now, was passing the stranded Greenfly. Suddenly ominous clouds of smoke were seen rising from S9. One of the gunboats was immediately ordered to return to the stricken vessel but when it arrived alongside it was found that the ship had been abandoned and was in flames. It was later discovered that S9’s engines had failed and she had drifted up against the river bank. It had then been boarded by a large group of insurgents who killed its crew and the two British officers and platoon of Indian troops on board.

The remainder of the flotilla continued steaming up to Samawa, continuously under fire from both banks of the river, but two miles south of the town one of the barges being towed by the remaining merchant vessel grounded on a mudbank and had to be abandoned. By evening of 28 August the flotilla reached the supply camp at Samawa but there had been heavy casualties among the crews and escort of Indian troops and a substantial proportion of the supplies had been lost. The only really successful aspect of the operation was that the forty-five men of the 123rd Rifles sent as reinforcements for the garrison arrived unscathed.

By now the situation of the troops defending the railway station was becoming desperate. Lying only 200 yards under the walls of the insurgent-held town, it was possible for the rebels to pour a deadly fire down upon Station Camp and within a short time, they punctured a number of the camp’s water tanks. By 3 September it was clear to Major Hay that the position of the men at Station Camp and Barbutti Bridge Camp, was untenable and he therefore ordered them to withdraw into the defensive perimeter surrounding the Main and Supply Camps. The Barbutti Bridge troops accomplished this without incident, but as the men at Station Camp began to move out disaster struck.

The plan was for around half the men of Napier’s Rifles, led by Lieutenant Fleming, to march down the railway line in the direction of Main Camp while 200 men of the Mahrattas would sally out to meet them at a point about 400 yards from the station. Meanwhile the remainder of the Station Camp garrison would be loaded into the trucks of the armoured train which would then advance in the same direction. Lieutenant Russell and the medical officer, Captain Pigeon, would accompany the train.

However, as the armoured train pulled out of the station it hit some faulty points and jumped the tracks. Seeing this, around 3,500 insurgents poured out of the town and charged towards it. Lieutenant Russell ordered his men to make their escape towards the Mahrattas’ lines as best they could. Led by Lieutenant Fleming, they soon encountered large numbers of rebels and while most of them broke through and joined their comrades, a number were killed while others were forced back into the armoured train, where they rejoined the remaining two British officers who had stayed with the wounded and sick.

From Main Camp, and at distance of about one mile, Major Hay was able to see the derailment of the armoured train through his field glasses and he began to collect every available man to make a counter-attack against the rebels who were now swarming all over Station Camp. But by the time he had mobilised sufficient men, all sound of firing from the vicinity of Station Camp had ceased and the rebels appeared to be dispersing. Again, the commanding officer scanned Station Camp through his field glasses; but an eerie calm had now settled over the scene of the action. Could anyone still be alive on the train? It didn’t look like it. Should he therefore sally out towards Station Camp with a force sufficiently large to rescue any survivors and defend itself if attacked, but thus inevitably denude Main Camp and put that crucial position at risk of being overrun?