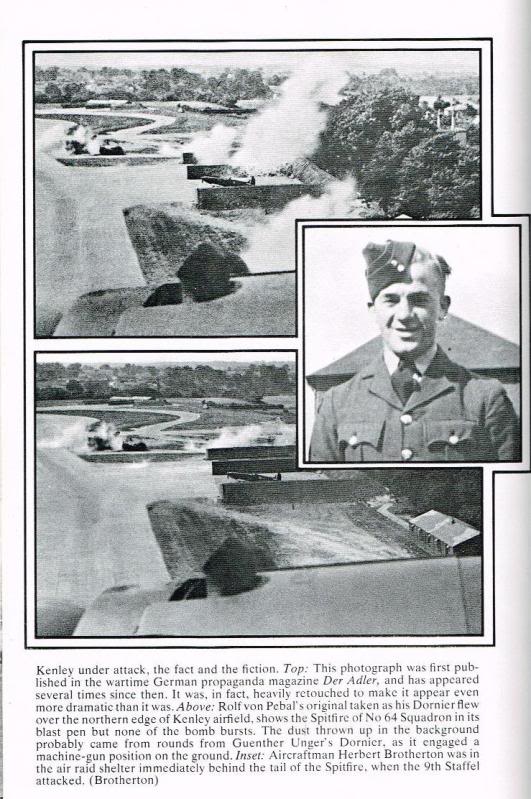

RAF Kenley under attack on 18 august 1940, seen from a Do 17 of KG76. KG76 lost six aircraft that day, and eight more staggered back to France with dead or wounded crew members.

18 August has gone down in the history books as ‘The Hardest Day’. During its course, Fighter Command lost 30 Hurricanes and seven Spitfires, but shot down 61 enemy aircraft, including 16 Bf 109Es. But the most decisive defeat of the day was that of the Stukagruppen, which lost 17 aircraft (adding to 39 lost during the previous two weeks).

After sending over a wave of high flying recce aircraft, Kesselring launched a major raid against Biggin Hill. Planned as a coordinated attack, the raid became two separate raids, the first by Do 17s, the second by Ju 88s. Two of the Do 17s were shot down immediately, and two more crashed in the Channel, while three more force-landed in France. One of the two aircraft which regained its base did so with a dead pilot, the young flight engineer taking over to fly back to his base and make a normal wheels-down landing. Feldwebel Wilhelm-Friedrich lllg won a well-deserved Knight’s Cross for his achievement. The wave of Ju 88s also lost two aircraft shot down.

An attack on Kenley was more successful, though two of the raiders were destroyed by parachute-and-cable anti-aircraft devices.

Nine Dorniers of KG 76 roared over Kent at a height of 100 feet or less, startling anyone who happened to be outdoors. The bombers had not been detected by the CHL station at Beachy Head, but the Observer Corps had spotted them and reported their presence.

The Dorniers had been assigned to bomb Kenley. Along with this low-level raid, KG 76 also had some of its Do 17s approach from high altitude. The combined attack brought a hail of 50 kg. (110 lb.) bombs to the airfield; one of the aircrew saw them bounce down the runway ”like rubber balls.” It seemed that they had done a thorough job on Kenley. Now, all they had to do was get back home again.

Thanks to the Observer Corps’ warning, Kenley’s anti-aircraft gunners were at their posts when KG 76 arrived. Every machine gun on the station began firing, and the PAC (Parachute and Cable) crews began launching their rockets at the Dorniers. Each rocket carried a 500-foot length of steel cable with a parachute at each end. If an airplane ran into the cable, the two parachutes would open and send the unfortunate victim spinning into the ground. At least, that is what everybody thought would happen nobody had actually tried them out yet.

The low-level Dornier attack was tailor-made for the PACs. And the awkward-sounding weapon worked. Much to the surprise of their crews at Kenley. A Dornier piloted by one Feldwebel Petersen caught its wing on one of the rocket-propelled cables. Both parachutes opened, jerking the bomber into an involuntary snap-turn. Before Petersen had time to react, his airplane crashed to earth and exploded.

While the PAC crews were doing their best to stop the low attack, Hurricanes of 32 Squadron intercepted the high-altitude attack Do 17s escorted by Bf 110s with a head-on rush. At least one of the Dorniers was destroyed during this charge; it fell out of formation and spun toward the ground out of control. The other bombers took evasive action, which resulted in the bomb-aimers missing their targets.

Meanwhile, the Hurricane pilots of 615 Squadron were taking on the Bf 109s that were flying top cover for the Dorniers and Bf 110s. In the ensuing melee, 615 Squadron lost four Hurricanes (and one pilot), while JG 3 parted with two Messerschmitt 109s (and one pilot).

Some 12 personnel were killed, and 10 Hurricanes and a pair of Blenheims were destroyed in the bombing. Five more Hurricanes were shot down by Bf 109Es, which swept in to cover the withdrawal of the bombers. The Sector Operations Room was damaged, and a replacement was put into operation in a local shop. Disruption to telephone lines made it difficult for Sector Operations Centres to report to Fighter Command HQ, and this prompted an immediate revision of the emergency communications procedures.

A wave of attacks hit the airfields at Ford, Gosport and Thorney Island, and the Chain Home station at Poling, where Hurricanes and Spitfires massacred the attacking Stukas, shooting down 16, plus eight of their escorts, for six losses. Further waves of attacks followed, but none were particularly effective.

The Luftwaffe had lost 228 aircraft in the previous week, including 52 Bf 109s, while Fighter Command’s losses had totalled only 105 aircraft. Moreover, Luftwaffe losses had included a Geschwaderkommodore, several Gruppenkommandeur and several Staffelkapitans, experienced officers who were impossible to replace. But on the credit side, it believed that it had destroyed 664 RAF aircraft, and that it had permanently destroyed 11 of the 44 aerodromes it had attacked (Driffield, Eastchurch, Gosport, Hawkinge, Lee on Solent, Lympne, Manston, Martlesham Heath, Portsmouth, Rochester and Tangmere). Furthermore, it was estimated that Fighter Command had no more than 300 fighters left (and not 700) and so the Battle continued without much respite.