In March 1483 King Edward suffered something like a stroke and within a few weeks was dead. His heir, another Edward, was only twelve and therefore not possibly ready to rule, but that should not have been a problem because the boy had uncles—men of proven loyalty and talent—to govern on his behalf and guide him to maturity. On the paternal side was the dead king’s youngest and last surviving brother, Richard, Duke of Gloucester, still barely thirty but deeply experienced in the arts of war and governance. Opposite him was Anthony Woodville, Earl Rivers, eldest of the numerous ambitious brothers of Edward IV’s widow, Queen Elizabeth. There was a problem, however: bad blood between Richard (who was supported by many of the old noble families) and the upstart Woodvilles, who were resented bitterly because of the wealth and power that had come to them for no better reason than the fact that King Edward, while still a very young man, had impulsively married the obscure if powerfully attractive widow Elizabeth Woodville Grey.

Duke Richard, it is clear, saw the situation as fraught with danger for himself. Earl Rivers had a close relationship with their nephew, whereas Richard, who for years had been far from court governing the north as his brother’s representative, scarcely knew the boy. The duke need not have been paranoid to fear that if the Woodvilles could maintain custody of young Edward V—hardly an improbable development, considering that the child’s mother was the most prominent Woodville of them all—they could also control the government and destroy their rivals. Whatever his motives, whether he was driven by ambition, hatred, or fear, Richard struck first, setting in motion a series of atrocities that would not end until eight of the last ten legitimate Plantagenet males, five of them boys too young to marry, had died violently. He came down from the north and ordered Rivers to bring their nephew to him. When Rivers did so, both he and the boy were taken into custody. In short order Rivers was executed along with young Richard Grey, Queen Elizabeth’s son by her first marriage. Edward V and his ten-year-old brother were sent to the Tower, and Duke Richard had himself crowned.

Convulsion followed convulsion, and with each new upheaval the existence of Henry Tudor became both more significant and more precarious. The princes in the Tower were heard of no more—it was impossible to doubt that they had been murdered—and many of the men who had figured importantly in Edward IV’s regime left England rather than support the new King Richard III. Ineptly and for reasons that remain obscure, the Duke of Buckingham, probably the richest noble in England and a man whose royal blood gave him a claim to the throne, raised a rebellion not in his own name but in Henry Tudor’s. Francis of Brittany gave Henry a tiny fleet and army with which to invade England, but it was scattered by storms. By the time the ship carrying Henry hauled alone into Plymouth harbor, Buckingham had been defeated and executed and the rebellion was over. Richard’s agents met an advance party sent ashore by Henry and, by reporting that the rebellion had already succeeded, tried to lure him ashore. He learned the truth in time, however, and made his escape. Fresh storms then drove him into port in France, and with great difficulty he managed to make his way overland back to Brittany. When on Christmas Day the English exiles who had gathered in Brittany assembled at Rennes Cathedral and pledged to support Henry, their oaths must have seemed nearly meaningless. Equally empty was Henry’s promise, made that same day, to marry Edward IV’s eldest daughter, Elizabeth of York, then in sanctuary at Westminster Abbey with her mother and four sisters.

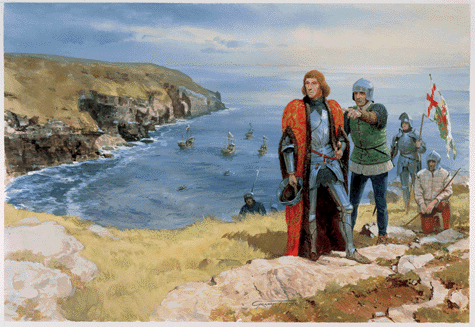

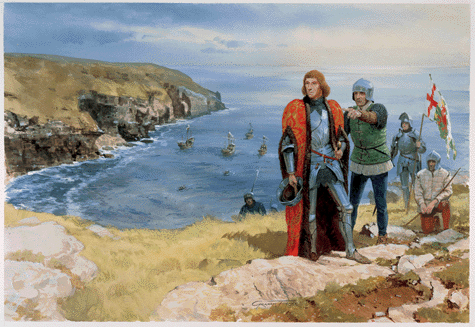

Worse soon followed. An exiled bishop with sources of information at the English court sent word that the Duke of Brittany was negotiating an agreement by which he would be richly rewarded for delivering Henry to King Richard. Henry opened communications with the French court and, upon establishing that he would be welcome there, laid plans to get himself and his followers across the Breton-French border. This ended in high drama: Duke Francis’s soldiers were hard on Henry’s heels as he galloped to France and safety. From that point, however, all his luck was good. The French king, Charles VIII, was a boy in early adolescence. His older sister, Anne of Beaujeu, headed the government as regent and badly needed to make trouble for Richard III, who was attempting to encircle France by allying himself with the two autonomous duchies of Brittany and Burgundy. (It is worth noting, in this connection, that Charles and Anne would have regarded young Tudor not only as a useful political tool but as a near kinsman. Henry’s grandmother Catherine of Valois had been their grandfather’s sister.) They added to the money coming to Henry from England to provide him with the means to again assemble some ships and hire a mercenary army. The resulting invasion force sailed out of Honfleur in Normandy on August 1, had good weather all the way this time, and made landfall at Milford Haven in the southwestern corner of Wales just six days later. It is said that Henry had to set one of his ships afire to prevent some of his more fainthearted troops from returning to France.

Richard, meanwhile, was experiencing much misery. His son and heir had died early in his reign, and when his wife died not long afterward, it was widely rumored that he had had her poisoned in order to free himself to marry his niece Elizabeth of York. The rumors became so damaging that he was obliged to take the humiliating step of denying them publicly. His subjects, evidently, were prepared to believe anything of him so long as it was sufficiently horrific. He made efforts to shore up his base of support—raising John Howard to Duke of Norfolk, for example, and giving offices and lands to the Stanley family—but the estimated number of his troops, when they came face-to-face with Henry Tudor’s on August 22, suggests that he should have done more along that line, done it sooner, and been more careful in selecting the beneficiaries.

We don’t know the size of the armies that faced each other that day. Henry must have had about five thousand men: several hundred displaced Englishmen who had made him the centerpiece of their quest for revenge, a few thousand thuggish soldiers-for-hire contributed by the regent of France, and a disappointingly small number—no more than a thousand or two, surely—who had joined him after he came ashore in southwestern Wales. Richard may have had twelve thousand, possibly ten, possibly fewer than that; the estimates vary, and there is no way of choosing among them. Whatever Richard’s total, it would have been cause for concern. It was pathetic compared to the thirty-five thousand or more troops that his late brother Edward IV had taken into the Battle of Towton on Palm Sunday in 1461, or the army of fifty thousand Lancastrians that Edward’s men had shattered that day. Richard had known months in advance that an invasion was being prepared. He had learned on August 11 that the invaders had landed four days earlier, and he had sent out summonses for the nobles of England and Wales, all of whom had been put on alert weeks before, to muster their soldiery and join him at Leicester. No more than one in every five had done so. It was unsettling evidence of how little support Richard had, and of how badly the old feudal system had decayed.