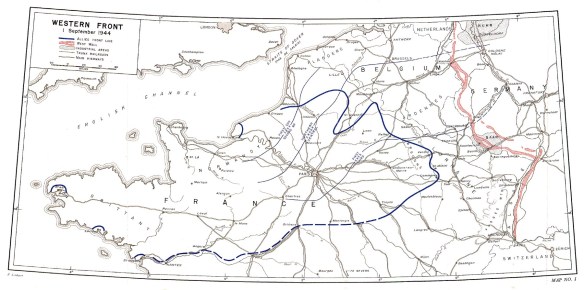

During the second ten-day period in September, the focal points of combat operations were located in the area between Arnhem and Nancy. The development of the situation along the outer wings of the front, however, turned out to be no less significant for the further course of events in the Western theater of war. In contrast to the front’s center, where positional warfare had already stabilized along extensive sectors, the German lines were still fluid both in the north and in the south.

The retreat operation from southern France was halted in the Dijon bridgehead on orders from the High Command. After Hitler’s plan to shift directly to a major offensive from the protruding frontline salient had failed, Blaskowitz finally was given approval to withdraw the exposed left wing of the Western Front. The corresponding Wehrmacht High Command order, however, included the restriction that the withdrawal movement could be carried out only under enemy pressure. But the Allied pressure against the Nineteenth Army abated precisely at that very moment.

The Allied Operation DRAGOON units coming from the south were ordered to go into a laborious regrouping operation on September 14. The two French corps were to be combined on the right wing before Belfort. General Truscott’s American units were to take over the left wing, which was oriented toward Strassburg. For the time being, there were no major offensive operations along the U. S. Seventh Army’s northern wing. The advance of the U. S. XV Corps became more hesitant after the major success at Dompaire. Patton had instructed Major General Wade Haislip to postpone his thrust across the Mosel River. The commanding general of U. S. Third Army believed that a cautious advance was in order, obviously in response to the appearance of the 112th Panzer Brigade.

Quiet for the first time prevailed along the front line of the Nineteenth Army on September 16. But that meant that there was no decisive situation upon which the Wehrmacht High Command could have based the completion of the withdrawal. The German headquarters in the west, however, were justified in believing that it made no sense militarily to wait until the Allied attack preparations had been completed in that sector of the front. Lieutenant General Walter Botsch, chief of staff of the Nineteenth Army, noting the army’s overextended lines, judged that the security screen was so thin, “. . . that one need not wonder if it simply snaps one fine day.”

Rundstedt and Blaskowitz, therefore, agreed to have the Nineteenth Army withdraw more rapidly into a shortened position. The commander of Army Group G hoped that this would allow him to constitute some reserves and to send the resultantly released forces of the Fifth Panzer Army to close the frontline gap in the Nancy area. In the evening of September 17, without enemy pressure, General Wiese issued the orders. His Nineteenth Army would finally evacuate the frontline salient the following night. Hitler issued a counterorder that an accelerated withdrawal was out of the question; but that order arrived too late-at least according to Rundstedt-to stop the movement.

Throughout September 18, Wiese’s units moved back into a frontline trace that ran roughly north-south from the Mosel River at Chatel via Epinal-Remiremont to the Belfort area. The operational level threat of the Nineteenth Army being cut off was over, and the final stage of the great retreat operation from southern and southwestern France was finished. Blaskowitz had played a decisive role in the final outcome. What had started with a catastrophic initial situation produced impressive results in the end. The southern sector of the German front line had been stabilized-at least for the time being.

Of the some 235,000 soldiers who had started on the march back, more than 160,000 reached the Dijon bridgehead. On September 20, the Nineteenth Army headquarters still reported a ration strength of 130,000 troops. Like OB West, Hitler at the end of August also had doubted that Blaskowitz would accomplish the difficult operation successfully. But Hitler no longer felt obligated by his comment at the time that he would ask Blaskowitz’s pardon if he pulled it off. Blaskowitz’s “mistake” in not holding the deployment area for Hitler’s offensive from the move overshadowed the success of the withdrawal. The die was now cast for a change in command. Himmler and some other Nazi Party functionaries apparently had long been preparing the ground for Blaskowitz’s removal. The justification for that action was based on the speed of the Nineteenth Army’s withdrawal, which had been too fast to suit the führer’s taste.

Rundstedt supported Blaskowitz with the very clear statement that all the withdrawal actions had been unavoidable considering the relative strength situation. There was, therefore, no blame that could be laid against the commander of Army Group G, and furthermore Rundstedt himself bore full responsibility for everything that was happening in his area of command. Hitler nonetheless refused to change his decision. Even before the change in command became official, rumors were rife at Army Group G headquarters in Molsheim. The background may not have been known, but the incident that cost Blaskowitz his position certainly was.

The reaction of the chief of staff, then, was only logical. Gyldenfeldt told Colonel Friedrich Schulz, the Nineteenth Army operations officer, that in the future there should be a little more verbiage in the reports on enemy activities so as to justify to the High Command any gradual withdrawal to the Vosges Mountains that would become necessary sooner or later. According to the activity report of the chief of the Army Personnel Office, Hitler made his decision on September 19. Blaskowitz’s relief was ordered, the report states with unintended irony, because the retreat operations had not been conducted in the manner intended. That undoubtedly was true, but in a sense completely different from what had been meant. The Germans, in fact, had expected the worst as soon as the Operation DRAGOON forces began their campaign of maneuver in Provence. It was primarily to Blaskowitz’s credit that the worst-case scenario did not occur. The campaign of maneuver had now drawn to an end in the south. On September 21, General of Panzer Troops Hermann Balck arrived in Molsheim to take command of Army Group G. He would lead the army group during the new phase of the fighting.

#

In the meantime, there were no major Allied attacks in the Nineteenth Army sector or on the right wing of the Western Front prior to the start of Operation MARKET-GARDEN. The relative quiet in front of the main line of resistance of the Fifteenth Army and the First Parachute Army was tied to Montgomery’s impending major offensive. The intelligence section of Army Group B had analyzed the objectives of the British commander early and accurately. Since September 8 the Germans had assumed that Montgomery’s center of gravity was no longer in the area of the Scheldt River estuary. The preparations of the 21st Army Group now indicated an offensive by way of Eindhoven into the area of Arnhem-Nijmegen-Wesel. Just five days later the German assessment was confirmed by reports of minor enemy attack activity against the bridgehead south of the Westerschelde River. The Allies obviously were planning to conduct a major offensive “in a northeasterly direction to encircle all German forces in depth in Western Holland.”

Accordingly, the main effort had to be on the eastern wing of the 21st Army Group. That was indicated by the fact that Dempsey’s British Second Army tried to extend on both flanks the wedge that was pointing toward Eindhoven, since that wedge probably was intended as the springboard for the offensive. The British were successful, forcing the center and left wing of Colonel General Kurt Student’s First Parachute Army to withdraw and evacuate the area between the Albert Canal and the Meuse-Scheldt Canal.

The Canadian advance toward the bridgehead south of the Scheldt River, however, became even more hesitant. The attempt to cross the Leopold Canal at Moerkerke failed with bloody losses on September 14. Lieutenant General Guy Simonds, the commander of the Canadian II Corps, then confined himself “to maintain contact . . . without sacrificing forces in driving out an enemy, who may be retreating.” Montgomery’s instructions to the Canadian First Army contained the misleading instruction that the opening of the Scheldt River mouth “will be a first priority for Canadian Army” and “The whole energies of the army will be directed towards operations designed to enable full use to be made of the port of Antwerp.” That, however, was irrelevant, at least for the next several weeks. Instead, Montgomery at the same time ordered Lieutenant General Crerar to capture the ports of Boulogne and Calais. Thus, only the Canadian 4th Division and the Polish 1st Armored Division up to that point were available for the task of attacking the German bridgehead along the Scheldt River. According to Montgomery’s enemy order of battle estimate, there were only relatively weak forces on the western wing of his army group in the Brügge-Antwerp- Herentals area.

That explains why General of Infantry Gustav von Zangen considered the Canadian units that followed his Fifteenth Army to be just one of his problems. The question of whether the major retreat operation of the Fifteenth Army across the Scheldt River could in the end help stabilize the German Western Front depended on other factors. The very feasibility of the difficult crossing operation itself even remained in doubt for the time being. But that crossing offered the only prospect at all of supplying the First Parachute Army with additional forces in time before the anticipated British offensive achieved an operational-level breakthrough in that sector. Furthermore, it was important for Zangen to block the Scheldt River mouth in such a lasting fashion that the Allies would be denied the logistic exploitation of the harbor of Antwerp for as long as possible. The immediate plan, therefore, was to leave four divisions, in other words half of the Fifteenth Army, back in that area. The 64th Infantry Division was to defend the Breskens bridgehead; the 70th Infantry Division was to defend Walcheren; the 245th Infantry Division was to defend Südbeveland; and the 331st Infantry Division was to defend the islands located to the north and all the way to the mouth of the Meuse River.

The remaining four divisions were earmarked for commitment on the mainland to support the main front of Army Group B. Besides the 64th Infantry Division, which remained behind on the south bank of the Scheldt River, seven major units had to cross the five-kilometer-wide estuary.

Two of those units reached the mainland by September 14. General of Infantry Otto Sponheimer’s LXVII Army Corps with the 346th and 711th Infantry Divisions had already reinforced the right wing of the First Parachute Army in the Antwerp area. Nevertheless, the forces of Student’s army, in Field Marshal Model’s estimation, would not suffice to beat back the impending British offensive- even after the arrival of the hastily refitted 10th SS Panzer Division.

There was, however, no way to speed up the retreat operation across the Scheldt River. Earlier, Allied aircraft had been able to block temporarily the harbor exit at Terneuzen by sinking several barges. A second major ferry connection also was interrupted temporarily by air raids on September 15. Allied bombers heavily damaged the Breskens landing. In addition to the two main ferries, the Germans since September 12 also had been using the passage between Doel and Lillo, about fifteen kilometers northwest of Antwerp. But that ferry link was within the range of Canadian artillery. On September 16, the artillery fire was so heavy that all crossing traffic came to a halt. There was, however, never a complete standstill. Because of the threat from the air, the movements of troops and equipment and the berthing operations of the boats now took place only during the hours of darkness or in fog. Despite the tremendous difficulties, the retreat operation continued. The very possibility of such an operation was a masterpiece of coordination by the German army and navy elements involved.

The indirect but hardly voluntary support from the Dutch also played no inconsiderable role. Krebs, for example, ordered a delay in the demolitions at the ports of Amsterdam and Rotterdam, although clearance had already been given by OB West. Krebs was afraid that the otherwise expected change in the mood of the Dutch population would have negative consequences for the Fifteenth Army. He emphasized that Zangen’s forces depended on Dutch vessels, at least until September 21.

The key point to remember here is that any Allied main efforts were now somewhere else-not in the area of the Scheldt estuary and Antwerp. Even the Canadian II Corps, which was operating against the Fifteenth Army’s bridgehead with two divisions, opened another effort on September 17, with the attack on Fortress Boulogne. After a heavy bombardment of the port city, the Canadians jumped off with one infantry division and two tank regiments, supported by 330 artillery pieces. On the German side, Lieutenant General Ferdinand Heim faced the attackers with just about ten thousand men.

At just about the same time, Operation MARKET-GARDEN, the long-anticipated Allied major offensive, started some three hundred kilometers farther to the northeast. By that point two corps headquarters and five infantry divisions of the Fifteenth Army had already crossed the Westerschelde River. Three of those units were in the meantime committed on the mainland. That undoubtedly facilitated Model’s defensive measures at the new focal point of crisis in Army Group B. Considering the situation, the field marshal also requested the commitment of the 712th and 245th Infantry Divisions. Those two units were still waiting to cross the river to be moved into the Tilburg area. The crossings were accomplished, although the situation south of the Scheldt River was now becoming critical. Advancing along the Ghent-Terneuzen Canal, Lieutenant General Simonds’s tank units penetrated deeply into the German defensive positions on September 19.

The eastern part of the German bridgehead had to be abandoned, and the ferry transport operations were shifted entirely to Breskens. The German units, including the 712th Infantry Division, that were stationed between the Ghent-Terneuzen Canal and in the area northwest of Antwerp were able to cross at Doel. Once that was accomplished, the ferrying operations were finally halted there as well. The Canadian attack, however, had come too late and failed to produce any decisive results.

By September 22 the last units of the 245th and 712th Infantry Divisions had evacuated the bridgehead. Nonetheless, eleven thousand troops of the 64th Infantry Division remained behind to defend Fortress Scheldt-South. Altogether, about eighty-five thousand German troops and more than 530 artillery pieces, 4,600 vehicles, and 4,000 horses had been ferried across the Westerschelde River.

Compared to the impressive numerical results of this German “little Dunkirk,” any success achieved by the Canadians hundreds of kilometers farther to the west were rather insignificant. The capture of Boulogne did not produce any direct advantage for the Allies. The approximately ninety-five hundred German soldiers taken prisoner there left behind harbor facilities whose infrastructure had been paralyzed to such an extent that it was useless for Allied logistics operations for the immediate future.

By far, the most decisive aspect of the combat operations on September 22, 1944, was the successful completion of the German withdrawal movement across the Scheldt River according to plan. That most probably would not have happened if the Canadians had not diverted so much of their combat power to the capture of Fortress Boulogne. The net result was that the major retreat operations of the German Army of the West had now come to a halt. And as a direct result, the Germans were able to shorten their front lines on the two outer wings, thereby freeing up forces that were badly needed at other critical points in the fighting.

Five divisions of the Fifteenth Army had reached the mainland since the middle of the month. In the judgment of General of Infantry Gustav von Zangen, those soldiers still retained an absolutely strong fighting spirit after the successful retreat operation. And those five divisions reinforced Model’s Army Group B at just the right moment. Those reserves facilitated Model’s defensive measures during the extremely critical phase of reactions to Operation MARKET-GARDEN.