Located on the western third of Hispaniola, in what is now Haiti, Saint-Domingue was ceded to France in 1697. By the second half of the eighteenth century, it was a leading exporter of tropical staple crops, with a population of about half a million slaves, thirty thousand free blacks (often called mulattoes), and forty thousand white colonists. The revolt that began in 1791 was a complex and many-faceted series of events, influenced in part by the American Revolution (1775-1783), during which some Saint-Domingue mulattoes joined other Frenchmen in fighting against the British. In 1790, two years after the French Revolution began, Saint-Domingue’s mulattoes staged a revolt that government troops quickly quashed. But the following year, an act of the French National Assembly extended citizenship to a large proportion of the colony’s mulatto population and, in addition, it began debating whether slavery should be abolished in the French Empire.

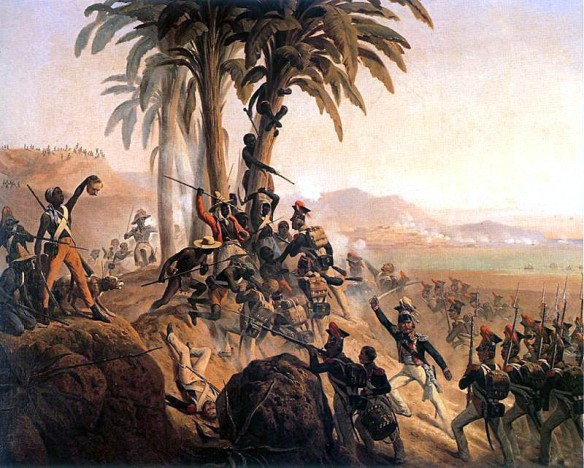

While the National Assembly moved slowly on the issue of abolition, the slaves of Saint-Domingue took their fate into their own hands. Led by a voodoo spiritual leader named Boukman, they rose against their masters in August 1791 and soon gained control over much of the northern countryside near the town of Le Cap (presentday Cap Haitien). Intending to destroy all plantations, they set fire to buildings and crops and created a cover of smoke so dense that for nearly three weeks, according to a contemporary source, the people of Le Cap could barely distinguish day from night. The rebels killed whites indiscriminately in revenge for the cruelties many of them had suffered, and government forces responded in like manner. According to historian C. L. R. James, twenty to thirty captured slaves were daily “broken at the wheel” (a form of execution in which the condemned was tied to a five-pronged table while each of his limbs was broken with an iron bar, after which he was killed with a blow to the chest). And as was sometimes the custom for executed criminals, their severed heads were placed on pikes along the road to Le Cap.

Despite the brutal punishment, thousands of slaves as well as mulattoes and even some whites joined the rebellion. Boukman was killed in an early skirmish, but other leaders such as Jean Francois and Georges Biassou took over the leadership. They were soon joined by Toussaint de Breda, a recently emancipated slave with uncommon intelligence and leadership ability. Toussaint distinguished himself by training fugitive slaves into effective soldiers and serving as an able negotiator for the rebels. A genius at organization and tactics, he quickly became a key leader of the rebellion, known as Louverture, meaning the opening, in recognition of his valor in creating a gap in the ranks of the enemy. By 1794 he had a large following, including several mulattoes and some white officers.

The early years of the rebellion were chaotic as patriots (defenders of the French Revolution) and royalists (its opponents) fought each other, as did wealthy planters and poor whites. Even free mulattoes, many of whom owned slaves and opposed abolition, vied with slaves for leadership of the rebellion. Under the leadership of Andre Rigaud, the mulattoes gained control over southern and western parts of Saint-Domingue, while Toussaint’s forces temporarily formed an alliance with the Spanish of Santo Domingo and gained control over the northern and central regions of Saint-Domingue.

As the French Revolution progressed, its leadership became increasingly radical. By 1792 the monarchy was replaced by a republic, which declared war against Britain and Spain the following year. Most of Saint-Domingue’s colonists and many mulattoes welcomed the twenty-five thousand invading British troops who captured the island’s coastal ports and fortifications and defended slavery. But when tropical diseases killed over half of the British soldiers, Toussaint was able to drive the surviving troops from the island and then conquer neighboring Spanish Santo Domingo. When the revolutionaries abolished slavery in 1794, Toussaint declared his loyalty to the French Republic, which in turn appointed him deputy-governor and commander of the island’s army.

Despite the official abolition of slavery, conflict in Saint-Domingue continued between whites and blacks and between mulattoes and emancipated slaves. By 1800, however, Toussaint had secured his leadership and was recognized as governor of the colony by France. But when Toussaint’s government produced a constitution that established him as governor for life, it greatly irritated Napoleon Bonaparte, who ruled France in various capacities for much of the period 1799-1815. After making peace with Britain in 1801, Napoleon openly turned against Toussaint, rescinded the abolition of slavery, and sent nearly fifty thousand troops to reestablish his authority over Saint-Domingue. Lured into a meeting with French authorities, Toussaint was arrested and deported to France, where he died in prison in April 1803. Meanwhile, black generals led by Jean-Jacques Dessalines defeated the French troops in Saint-Domingue and permanently secured the colony’s independence. Crowned emperor in 1804, President Dessalines gave the country its new name-Haiti.

The Haitian Revolution had widespread repercussions. Although it cost some two hundred thousand lives-mostly African Americans, but also at least fifty thousand European settlers, soldiers, and sailors-the rebellion produced “the world’s first example of wholesale emancipation,” bringing freedom to nearly half a million slaves. It also brought the greatest degree of social and economic change of any slave revolt, leaving the most productive colony of the day in ruins, eliminating its ruling class, and establishing an independent black state. And for years to come, so-called French slaves and free blacks from Haiti participated in rebellions throughout the Caribbean region.

Toussaint Louverture (ca. 1744-1803)

Born to slavery in French-controlled Saint-Domingue, on the island of Hispaniola, Toussaint Louverture is regarded as the founding father of its successor state-Haiti. Born about 1744 as Toussaint de Breda, he made good use of opportunities for self-education, learned to read and write, and was entrusted with considerable responsibility, which led to his manumission in 1791.

Shortly after gaining his freedom, Toussaint joined the uprising of Saint-Domingue’s slaves that launched a decade-long struggle for freedom. A genius at organization and tactics, he soon became one of the leaders of the rebellion and became known as Louverture, meaning the opening, in recognition of his effort to create a gap in the ranks of the enemy. He collaborated for a while with the Spanish in Santo Domingo, but after the French revolutionary government became more radical, it recognized Toussaint as the principal leader of the rebels. He drove invading British forces from the western coast of the island, put down an attempted coup by mulatto generals, and was appointed Governor- General of Saint-Domingue after France abolished slavery in 1794.

When, by 1801, Toussaint had gained control over virtually all of Hispaniola, including Spanish Santo Domingo, he strengthened his position by reorganizing the government and establishing a constitution that made him governor for life. Meanwhile, the government of France had become more conservative. After Napoleon declared himself emperor in 1802, he rescinded the abolition of slavery and sent a large military force to Hispaniola to reestablish the slave system. While several black generals cooperated with the French, Toussaint withdrew to his private estate. In June 1802, Toussaint was betrayed by former associates and tricked into a conference with the French military commander, General Leclerc, who arrested him and had him deported to France. Having incurred Napoleon’s disfavor, Toussaint was ordered a harsh and degrading imprisonment that caused his death on April 7, 1803.

The rebel forces prevailed in Saint-Domingue even without Toussaint and defeated the disease-weakened French troops. The victorious rebels renamed the country Haiti in 1804, and Toussaint came to be honored as a founding father.