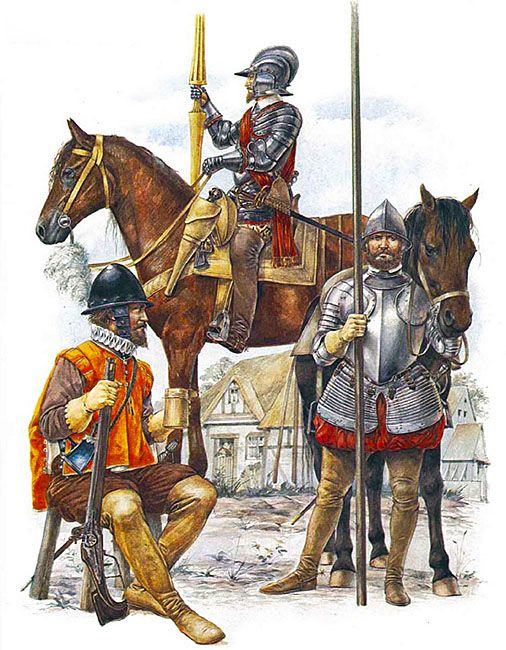

“The Armada Campaign, 1588: • Petronel, Earl of Essex’s troops • English demilancer • English light horseman”, Richard Hook

English; The Armada Campaign, 1588- English Officer, English caliverman & English pikeman by, Richard Hook

By George Gush

It seems logical to start with the English army of this period, though it in fact saw relatively limited service against other nations – a couple of expeditions to France, two wars and various troubles with Scotland, aid to both sides in the Netherlands and to the Huguenots in France, lengthy wars in Ireland, and preparations against various invasions which never came. Nonetheless it makes an interesting modelling or wargaming subject, since it differed from most other nations’ forces, firstly, in being raised on a militia system, with local authorities supplying clothing and arming their contingents, and secondly, in weaponry, where England tended to be somewhat behind the times, retaining bill, bow and cavalry lance long after their general disappearance elsewhere.

Infantry weapons and organisation

In the early 16th Century, nearly all were the traditional billmen and longbowmen, both usually equipped with a ‘jack’ (leather coat, usually knee-length, lined with iron plates) and with a simple rounded helmet of ‘skull’ or sallet type. Even by the 1550s this was still true, corselets and morions being rare, and multi-layered canvas jackets or even mail shirts being still favoured.

Henry VIII, the only military-minded English monarch of the period, began reform; as well as instituting home production of artillery and armour, he imported weapons in quantity (many are still at the Tower) and encouraged the adoption of artillery, the pike, and hand firearms. However, among 28,000 English foot taken to France in 1544, there were less than 2,000 arquebusiers, and billmen out numbered pikemen three or four to one. Henry had to hire Spanish and Italian arquebusiers and German pikemen.

However, the older weapons were gradually supplanted by the new, and in 1558 English companies in Ireland had about 50 each of longbowmen and arquebusiers. A Leicester- shire company of 1584 shows a later stage in the transition, having 80 pikemen and 80 men with firearms, as against 40 billmen and 40 archers. Though Sir John Smith wrote approvingly of this organisation in the 1590s, and recommended the formation illustrated, he was a longbow-enthusiast, and it seems likely that the 1580s saw both the appearance of the musket and the disappearance of the bow from English first-line service. The London Trained Bands dropped the bow in Armada year, and in 1595 it was ruled unacceptable for trained bands ‘shot’ generally.

English infantry companies varied from 100 to 400 in strength, Sir Roger Williams apparently considering 150 standard in the 1590s.

Here are some further examples:

1558 150 armoured pikemen, 150 unarmoured pikemen, 100 arquebusiers.

1596 50 pikemen, 12 musketeers, 36 calivers.

1599 30 pikemen, 10 ‘short weapons’, 30 muskets, 30 calivers.

1600 20 pikes, 10 halberds, 6 sword-and-buckler, 12 muskets with rests, 12 ‘bastard’ (light) muskets, 40 calivers.

The word ‘Regiment’ was used in Henry VIII’s time to describe the three medieval-type ‘battles’ into which armies were still divided (in 1544 13,000 – 16,000 strong). Each of these would mass its billmen and pikemen together in from one to three large blocks, with ‘wings’ of archers and other shot operating on their flanks. ‘Regiment’ still had a very vague meaning in the mid-16th Century – all the troops operating in the Netherlands, 6,000 or more, forming one ‘Regiment’ – but by the later part of Elizabeth’s reign, regiments were fairly definite organisations, commanded by a colonel and, in Ireland, usually comprising five companies.

By this time, later helmets such as the morion had become almost universal among English as well as Continental infantry; calivermen still sometimes wore a plate corselet, while pikemen would wear corselet and often pauldrons and arm-protection, and tassets to cover the thighs.

Cavalry

‘Men at Arms’ with heavy lance, full armour, and often barded horse, were still used in the first half of the century, but were few in number though of high quality. In 1544 Henry VIII had his 75 ‘Gentlemen Pensioners’ or household cavalry, and 12t ‘men-at-arms’. Individual noblemen would also serve in full plate. Appearance of such troops would be much the same in any nation, though Englishmen might wear rounded Greenwich armour.

Much more numerous were the ‘demi-lances’, with corselet only, or threequarter armour, open burgonet, and unbarded horse. These men carried a light lance and later pistols as well, and formed the main English cavalry up to the end of the century.

Demi-lances formed about one-fifth of the English cavalry, the remaining four-fifths being the characteristic English light cavalry, referred to variously as ‘javelins’, ‘prickers’, ‘Northern spears’ or ‘Border horse’.

They were also armed with light lance and one pistol, sometimes carrying a round or oval shield as well, and wore an open helmet, mail shirt or jack (corselet for the wealthier individuals), leather breeches and boots. Such cavalry were supplied by several English counties, but the best came from the raiders of the Scottish border, who were reputed to spear salmon from the saddle!

Cavalry were always in short supply in English armies; Henry VIII supplemented them with Burgundians and Germans with boar-spear and pistols. In Ireland in the later 16th Century cavalry usually formed about one-eighth of an English army. In Henry’s time they were organised in ‘bands’, cornets, or squadrons of 100 men, later of about 50.

Dress

The general lines are indicated by the illustrations, and followed the pattern of civilian dress of the period. Even the standing force, the small Sovereign’s bodyguard of the Yeomen of the Guard (who served both on foot with bow and halberd and mounted with javelins) seem to have confined uniformity to jackets and caps. When raised by Henry VII the jacket was white and green with a rose on the chest: under Henry VIII and thereafter they wore red jackets, guarded in black, with rose and crown in gold, and red or black cap with white plumes, but breeches and hose could be of various colours. As gentlemen, the Pensioners probably scorned uniformity but the illustrations may give an idea of their dress. When they became Gentlemen at Arms under James I they wore red and yellow plums.

Militia contingents, which could be up to about company size, were supplied with uniform clothing, and some examples of this are listed below:

1540 London Trained Bands: white jacket, city arms front and back; some with buff jerkins.

1553 Canterbury: yellow.

1556 Reading: (billmen) blue coats with red crosses.

1550s Surrey: (demi-lances) red cassock with double white guard (border).

1558 London: white coats slashed green, with red crosses.

1560s Lancashire: (archers) blue cassock, double white guard, red cap, buckskin jerkin.

1560s Derby: light blue. Stafford: red.

1576 Lancashire: white cassocks with one red and one green lace.

1577 Lancashire: pale blue coat, double yellow or red guard, white doublet, pale blue breeches with red or yellow stripe down seam, white stockings.

1585 London: red (and in 1596).

1585 Essex: (pikemen) blue mandelion (tabard-like garment worn over armour).

1590 Canterbury: red.

1599 Essex: russet coat and hose.

Contingents raised by noblemen might be clad in family or other colours (for example the Earl of Surrey brought 500 men in white and green to Flodden) and it seems that larger groups were sometimes uniformed – at the siege of Boulogne, Henry VIII’s Main Battle and Rear Guard were dressed in red with yellow trim, the other forces in blue with red trim, and in 1556 8,000 English sent to aid Spain in the Netherlands all wore blue.

In the early t6th Century, white was a favourite colour for English troops (the Tudor colours were green and white); in the later part of the century red became the most widely used. Blue, however, was also widely worn, and for Irish service cassocks (loose long or short coats, sometimes hooded or sleeveless, worn over equipment) were usually to be of russet, green or ‘sad’ colours. Cavalry in Elizabeth’s reign seem to have favoured red, tawney or orange colours; Border Horse usually wore white, and could wear ‘blue bonnets’ like the Scots. English archers too often wore ‘scots caps’ in red or blue over their helmets, and cavalry helmets were likewise sometimes covered with red or parti-coloured caps.

The sign of the English soldier, worn on breast and back during the first half of the 16th Century, and found on shields and pennons later, was the red cross of St George. Toward the end of the century, sashes, worn about the waist or over the right shoulder by officers, and some pikemen and cavalry, became the usual national distinction. Red or red and white seems to have been worn by the English, though senior officers often wore blue or blue and gold. Officers were distinguished from their men, just as in other armies of this period, by armament (sword and buckler. half-pikes and partisans being favourite officers’ weapons), and by rich clothing with silk and lace, gold or silver trim, decorated armour, and jewellery.

trained bands.

Military advisers to Elizabeth I established ”trained bands” that built upon the country’s militia tradition to strengthen domestic forces in the event conflict with Spain led to invasion. The idea was to substitute a well-trained and properly equipped urban militia for the wholly inadequate and ill-equipped amateurs that preceded the trained bands. Nobles and clergy were exempt from trained band obligations since, theoretically, they already contributed through the older feudal levies.

arquebus.

Also “arkibuza,” “hackbutt,” “hakenbüsche,” “harquebus.” Any of several types of early, slow-firing, small caliber firearms ignited by a matchlock and firing a half-ounce ball. The arquebus was a major advance on the first “hand cannon” where a heated wire or handheld slow match was applied to a touch hole in the top of the breech of a metal tube, a design that made aiming by line of sight impossible. That crude instrument was replaced by moving the touch hole to the side on the arquebus and using a firing lever, or serpentine, fitted to the stock that applied the match to an external priming pan alongside the breech. This allowed aiming the gun, though aimed fire was not accurate or emphasized and most arquebuses were not even fitted with sights. Maximum accurate range varied from 50 to 90 meters, with the optimum range just 50-60 meters. Like all early guns the arquebus was kept small caliber due to the expense of gunpowder and the danger of rupture or even explosion of the barrel. However, 15th-century arquebuses had long barrels (up to 40 inches). This reflected the move to corning of gunpowder.

The development of the arquebus as a complete personal firearm, “lock, stock, and barrel,” permitted recoil to be absorbed by the chest. That quickly made all older handguns obsolete. Later, a shift to shoulder firing allowed larger arquebuses with greater recoil to be deployed. This also improved aim by permitting sighting down the barrel. The arquebus slowly replaced the crossbow and the longbow during the 15th century, not least because it took less skill to use, which meant less expensive troops could be armed with arquebuses and deployed in field regiments. This met with some resistance: one condottieri captain used to blind and cut the hands off captured arquebusiers; other military conservatives had arquebusiers shot upon capture. An intermediate role of arquebusiers was to accompany pike squares to ward off enemy cavalry armed with shorter-range wheel lock pistols. The arquebus was eventually replaced by the more powerful and heavier musket.

pike.

An infantry spear with a deadly (to armored man or horse) three-foot iron point mounted on an eighteen-foot wooden shaft. The pike probably originated in Italy (Turin), but was most famously deployed in the Swiss square and Spanish tercio.

In combat, pikes were held with both hands, a fact that left pikemen unshielded and vulnerable to archers and other missile infantry. Normally, the first four ranks extended their pikes at varying angles calculated to hit man or horse in the waist, chest, neck, or face. All horses and most men were bright enough not to charge headlong toward impalement on a hedgehog of deadly iron-tipped spears. That many died this way, nonetheless, resulted from being pushed from behind by the forward rush and momentum of the back ranks of their own side. To avoid this, some cavalry thinned their lines. More often, it became standard tactics to move archers or arquebusiers forward to break up the defending pike formation so that the heavy cavalry could charge into gaps created in the ranks and files and break it up further with lance and saber. In the typical new-measure-prompts-countermeasure pattern of all tactics and war, that device was countered by placing archers and musketeers inside the pike squares, or at its corners as in the Spanish tercio, or on its wings, from where they ran to the back of the square after firing off their weapon at the enemy’s missile troops. Such changes were incremental during the 16th century as missile weapons improved and more specialists were added according to battlefield experience.

Offensively, individual pikemen were next to useless because of the sheer unwieldiness of their weapon and their immobility and vulnerability if caught in the open. Pikemen therefore drilled in moving together, leveled pikes to the forefront with back ranks holding their spears vertical. Squares formed tightly packed hedges that bristled with ranks of lethal spears. Densely packed formations then moved on command into a forward trot, and kept pace to a chant or beaten drum. This presented the enemy with an unstoppable frontage of iron-tipped spears that combined shock with deadly momentum and penetration (“push of pike”). Facing a massed square of several thousand men, rear ranks pressing and pushing with shoulders down against the backs of men in front, the whole body moving as one, no cavalry could stand and few tried. Only another pike square might hope to hold its place in defense, pushing back after the stunning initial collision. Modern recreations have demonstrated that pike formations of 10,000 men could compress into an essentially impenetrable square 60 feet by 60 feet. Such formations pushed aside whatever resistance they met from archers or slow-firing fixed artillery, which they usually overran. Axe men and halberdiers in the back ranks then hacked apart any wounded enemy, as the square literally rose over and trod on the bodies of their enemies. Pikes were used in European warfare until the invention of the socket bayonet (1687) made every musketeer his own piker.