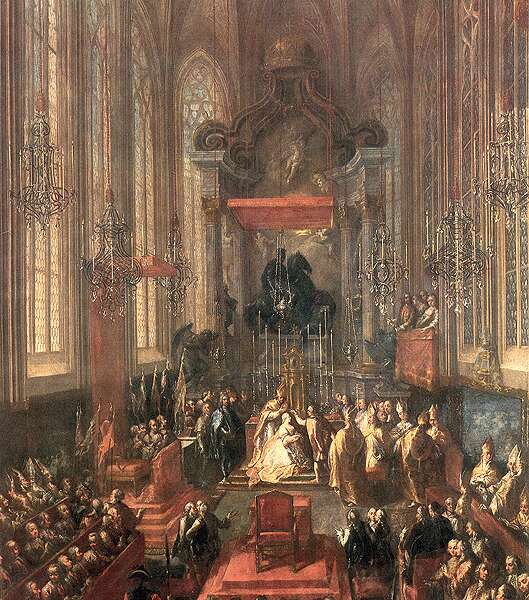

Maria Theresa being crowned Queen of Hungary, St. Martin’s Cathedral, Pressburg.

With unfailing political instinct Maria Theresa tried always to take into consideration factors relating to tradition in her dealings with the Monarchy’s most difficult country, and from time to time at least partly to win over the suspicious and eccentric nobility to the central reforms. Distribution of offices, decorations and personal marks of favour were of great help in these efforts. The Hungarian policy of the court was doubtless moulded by the Queen’s humane disposition. A few weeks before her death she summoned the Chancellor of Hungary, Count József Esterházy, to an audience and said to him: “Tell the Hungarians again and again that I shall think of them with gratitude until my very last moment.”

This attitude and her various educational, scientific and religious initiatives had far-reaching and sometimes unforeseen consequences for Hungary’s future, and indirectly for the Monarchy. Maria Theresa succeeded first and foremost in enticing the high and well-to-do section of the middle-ranking nobility into Vienna’s sphere of interest. In 1746 she established the Theresianum, the élite academy for training young nobles, which up to 1772 already attracted 117 sons of Hungarian aristocratic families. Numerous Hungarians also graduated from the Military Academy in Wiener Neustadt, and officers who attracted attention for their bravery were decorated with the newly-established Order of St Stephen. While Protestants were restricted in practising their religion and Jews were mercilessly persecuted and even occasionally expelled from Bohemia and Moravia, the pious Empress strongly supported the Catholic Church, partly in the interest of the Empire’s standardization. The victorious Counter-Reformation created a pro-dynastic but also explicitly Hungarian patriotism of a Baroque-Catholic flavour, culminating in the notion of the Regnum Marianum, deliberately linking it with the medieval national kingdom’s cult of Mary.

Two gestures in particular impressed the national-religious feelings of the Hungarians. After 1757 Maria Theresa again bore the title “Apostolic King of Hungary”, a new-old privilege, conferred by Pope Clement XIII in recognition of the Hungarian people’s sacrifice in the fight against the Turks. It harked back to the time of St Stephen, whose right hand was ceremonially repatriated from Ragusa (Dubrovnik) to the royal palace of Buda, to even greater effect.

As for national interests, although Transylvania continued to be separated from the mother country, Maria Theresa re-incorporated into Hungary the thirteen Zipser towns mortgaged to Poland 300 years earlier by King Sigismund, the port of Fiume and the Military Border districts of the Tisza-Maros region.

By far the most significant gesture for the future of the Hungarian language, literature and national identity—even if at the time it was not fully recognized—was the establishment in 1760 of a Hungarian noble regiment of the Queen’s Guards in Vienna. Two young nobles were sent to Vienna by each county to serve in it for five years, and to these were added twenty delegates from Transylvania. The Queen later raised the number of her Life Guard to 500. It is a paradox of Hungarian history that the renewal of the Hungarian language was not initiated in Hungary proper but in the capital of a foreign country, making Vienna the centre of the Hungarian literary movement.

It was an eighteen-year-old guardsman György Bessenyei (1747–1811) who, having mastered French and then German (he wrote poems in these languages), concluded that the ideas of the Enlightenment could only be spread through the mother tongue. That, however, required renewal of the language itself in order to adapt it to the higher intellectual demands. The second task was to motivate people to read, and the third was the creation of a literature to rouse their interest and lead them in the direction of reforms. It is not an exaggeration to regard Bessenyei the forerunner of the modern Hungarian language even though the style of his works, published from 1772 onwards, make them almost unreadable today. Nonetheless he and his friends gave the first impetus to language reform and the introduction of the language movement. The essayist Paul Ignotus, who wrote an English-language History of Hungary in emigration, may be correct in a deeper sense when saying that through his literary renaissance Bessenyei “had invented the Hungarian nation”. Previously only a handful of Hungarian writings, mostly religious, had been published. The first Hungarian newspaper, Magyar Hirmondó, printed in Pressburg, appeared first in Latin, then in German, and only from 1780 in Hungarian.

Through the philosophy and literature of the Enlightenment France exerted a strong cultural-linguistic influence on the Hungarian magnates, both directly and indirectly. Thousands of French books were housed in the libraries of the 200 castles built during Maria Theresa’s reign. One brilliant figure of the Hungarian Enlightenment was Count János Fekete, a general of half-French, half-Turkish background, who carried on a lively correspondence with Voltaire; he sent numerous French poems to the sage of Ferney, which the latter conscientiously corrected and praised, even asking his admirer to send new works. His interest in the versifying general may not have been purely literary, since Fekete always sent 100 bottles of Tokai with his poems.

Very few precursors of Romanticism took up the cudgels for Hungarian. Latin was the nobility’s second language—how else can one explain that the most revolutionary work of the period, Rousseau’s Le contrat social, was published in Hungary (and only there!) in Latin? John Paget wrote even years later: “Only the magnates. I suspect, have a better reason than mere courtesy for not speaking Hungarian—simply because they cannot do so. A large part of the higher nobility is denationalized to such an extent that they understand every European language better than their own national language.”

Maria Theresa was extraordinarily popular in Hungary, although the massive settlement (impopulatio) of foreigners decreed by her altered the ethnic composition to the Hungarians’ disadvantage. While the primary aim was to reconstruct the devastated and depopulated swamplands, the loyalty of the new settlers was not unimportant, in the words of Bishop Kollonics, “in order to tame the Hungarian blood, which is inclined to revolution and turmoil”. Since the end of the seventeenth century the Imperial Court regularly sent agents from Buda to Austria and Bavaria to recruit colonists with the promise of tax exemption for three to five years or immunity from the dreaded billeting. The mainstream of willing immigrants came from south-western Germany, particularly the neighbourhood of Lake Constance, central Rhenish villages and the Moselle region. Germans as such were preferred because of their diligence and loyalty to the Court. At first Catholics were favoured as settlers, but later Protestants were also accepted. Under Maria Theresa the Bánát and Bácska in southern Hungary were settled in this way; between 1763 and 1773 alone, the authorities dealt with 50,000 German families, and it is estimated that the number of settlers of German origin in 1787 was 900,000, i.e. a tenth of Hungary’s 9.2 million population.

Along with the creation of “loyal islets” of diligent Germans there was also an inconspicuous immigration of Slovaks and Ruthenes from the north, Romanians from the east and southeast (they were already in an absolute majority in Transylvania) and Croats and Serbs from the south. As a result of the catastrophes at the end of the Middle Ages and the Turkish occupation, Magyars in 1787 amounted to only 35–39 per cent of the population.

These statistics explain the shock which the partly organized and partly illegal influx caused to the distrustful middle-ranking and lesser nobility. Although Maria Theresa was masterly at manipulating the Hungarian aristocracy’s need for admiration and pride to her own advantage, she kept a watchful eye on a possible flare-up of rebellious ideas or nostalgia for Kuruc leaders:

One day Count Aspremont drove to his estate at Onod. The heavy coach sank into the mud, and the horses could not pull it out. While this was happening, peasants were dashing by in their light vehicles on their way from holy mass at Onod. None of them stopped. They only laughed at the predicament of the loudly cursing Germans stuck in the mud. Finally the Count climbed on to the coach-box, angrily shouting at the laughing peasants: “So you let Rákóczi’s grandson roll in the mud?” When they heard the name, they immediately hastened to the coach, pulled it out and, cheering, accompanied the Count to Onod. News of this adventure soon reached Vienna, and when the Count appeared at Court, Maria Theresa shouted at him, red with anger: “Listen, Aspremont! We don’t expect you to remain stuck in the slime, but you’d better forget about this Rákóczi farce, or we’ll have you but in prison!”

The massive settlement programme supported by the ruler was less a deliberate striving at Germanization than part of an attempt to centralize Hungary’s and the Habsburg Empire’s absolutist administration. In this context the Diet of 1764, the last during the Queen’s lifetime, signalled a momentous turning point. The Estates stubbornly and in the event successfully resisted the Queen’s determination to raise war taxes, tax the nobles’ private property and reduce the burdens of the peasantry. Maria Theresa nonetheless enacted by royal decree the “Urbarial Patent” rejected by the Diet, fixing the normative legal size for a peasant holding and the maximum services which the landlord could exact (in the Middle Ages the urbarium was the land and mortgage register). Although the Queen did not act overtly against the constitution and the nobility’s selfish and shortsighted opposition, from that time onwards she allowed a discriminatory economic policy to take its course against Hungary.

The underdevelopment resulting from the country’s colonial status enforced by Austria, as expounded by many Hungarian historians in the past, is seen differently and in a more sophisticated way today. Thus Kosáry points out that it was not the Austrian customs and trade regulations that made Hungary into a backward agrarian country and a buyer of Western industrial products; it merely exploited this situation. The Diet was never again called into session after 1764, and Hungary sank increasingly to the position of supplier of food and commodities to other crown lands. Although slow economic development did take place, the nobility’s insistence on tax exemption gave the Viennese bureaucracy welcome excuses for separating Hungary from Austria by an internal customs barrier and deliberately making Hungary’s already adverse position worse, with detrimental long-term effects on the other Habsburg lands as well. This continued till 1848.

In spite of her immigration and economic policies, Maria Theresa was and remained a generally admired and beloved ruler. On the other hand, the drastic reforms decreed by her son Joseph without any knowledge of human nature and a disregard for Hungarian sensibilities had far-reaching consequences, including loss of the old mutual trust. On the contrary, the imperial innovations dictated totally in the spirit of the Enlightenment gave an enormous stimulus to Hungarian nationalism, which in 1848 was to change the political map of Central Europe dramatically.