Following the victory at Valmy on 20 September 1792, the French seized the offensive. General Adam Philippe, comte de Custine’s Army of the Vosges captured Speyer, Worms, Mainz, and Frankfurt in barely a month, mainly because his otherwise easily panicked troops faced little opposition. The fortified city of Mainz, which capitulated on 21 October 1792, was a prize whose loss nine months later came to symbolize a tragedy of illusions and missed opportunities as well as valiant efforts. For contemporaries as well as modern historians, the principal significance of the episode was political rather than military, for the fall of the city was accurately thought to have presaged the French occupation of the Rhineland.

French troops-promising liberation to all peoples seeking assistance-along with the new local Jacobin Clubs set about revolutionizing the left bank of the Rhine. Though led by intellectuals and officials, Mainz Jacobinism was a cross-class movement that found resonance among the lower orders but never quite attracted mass support. As the idealism of its leaders collided with the reality of public skepticism or hostility, frustration and French power-political needs led to ever more coercive measures, recapitulating the transition of the Revolution itself from liberalism to authoritarianism. Finally, the new “Rhenish-German National Convention” declared the city and surrounding territories a republic independent of the Holy Roman Empire (18 March) and then sought union with France, whose republican government, heretofore forswearing any desire for territorial aggrandizement, now resurrected the old Bourbon objective of enlarging the country to include the “natural” frontiers-the Rhine, the Alps, and the Pyrenees.

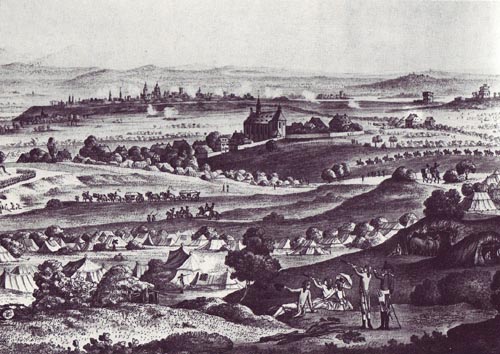

Threatened by Austrian forces and contingents furnished by the Holy Roman Empire, however, Custine withdrew the bulk of his troops. The Allies encircled Mainz on 30 March 1793, invested it on 14 April, began bombarding it on 18 June, and took it on 23 July. The departing French pledged not to engage the Allies for one year, and many joined the republican armies of the west, where their skill contributed greatly to the crushing of the Vendean revolt. The fate of their German collaborators was less gentle, ranging from harassment to prison terms, exile, and lynching. The most celebrated primary source is the account by Goethe, who accompanied the besiegers but who displayed great empathy for all participants (especially civilians) and a spirit of reconciliation all too rare among the victors.

The fall of Mainz, combined with other blows that summer, precipitated the levée en masse and the commencement of the Reign of Terror. Mainz changed hands several times in 1794-1795, but under the Treaties of Campo Formio (1797) and Lunéville (1801) was returned to France and became the Prefecture of the Department of Mont-Tonnerre. In 1814 Mainz was restored to its sovereign status.

Although one should beware of exaggerating the importance of the revolution in Mainz, it was the first modern German democratic movement. The problems it posed-the strengths and limitations of both force and idealism, the challenge of implanting democracy under occupation, and the dilemma arising when the majority will rejects democracy-remain topics for military and political reflection.

References and further reading Blanning, T. C. W. 1974. Reform and Revolution in Mainz, 1743-1803. New York: Cambridge University Press. Chuquet, A. M. 1886-1896. Les guerres de la révolution. 11 vols. Vol. 7: Mayence. Paris: Léopold Cerf. Dumont, Franz. 1993. Die Mainzer Republik von 1792/93: Studien zur Revolutionierung in Rheinhessen und der Pfalz [The Mainz Republic of 1792/93: Studies on the Revolutionizing of Rhenish Hesse and the Palatinate]. 2nd ed. Alzey: Verlag der Rheinhessischen Druckwerkstätte. Phipps, Ramsay Weston. 1980. The Armies of the First French Republic and the Rise of the Marshals of Napoleon I. Vol. 2, The Armées de la Moselle, du Rhin, de Sambre-et- Meuse, de Rhine-et-Moselle. London: Greenwood. (Orig. pub. 1926-1939.)