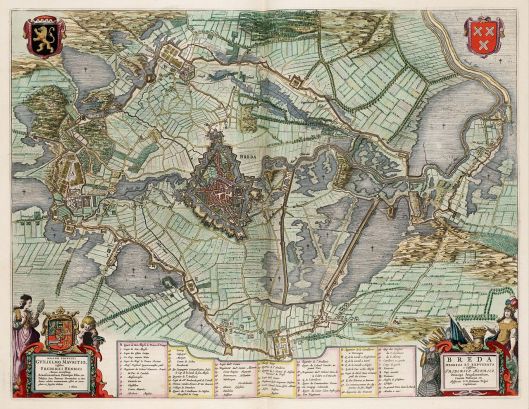

Map of the Siege of Breda by Johannes Blaeu.

Twelve years after failing to prevent Spanish capture of Breda, Frederick Henry of Orange besieged the fortress-city, held by Gomar Fourdin, flooding the surrounding country and driving off a relief attempt by Spanish Governor Cardinal Infante Ferdinand. The Dutch captured starving Breda after more than a year and gave the defeated garrison free passage (20 July 1636-10 October 1637).

Spain’s mounting problems concerned the Empire because they

undermined Philip IV’s war against the Dutch. A Spanish success in the

Netherlands would enable Ferdinand III to withdraw his troops from Luxembourg,

while a Spanish defeat would free France to reinforce its army in Germany. As

the war dragged on, Ferdinand urged his cousin to at least settle with the

Dutch and concentrate on the conflict with France. Spain viewed the events in

the Empire with similar impatience, failing to understand why the emperor had

not been able to crush Sweden after Nördlingen. Imperial commanders repeatedly

promised Spain cooperation during the winter planning rounds, only to march in

the opposite direction when the campaign opened to stop Swedish attacks on

Saxony or Bohemia.

The effects were felt in 1637, dispelling the optimism

following the Year of Corbie. The unexpected success of the unplanned invasion

of France in 1636 encouraged Olivares to switch three-sevenths of the then

65,000-strong Army of Flanders to Artois and Hainault for an invasion of

Picardy. However, he refused to surrender the remaining outposts on the Lower

Rhine to obtain peace with the Dutch, tying down the bulk of the other troops

in garrisons. Conscious that the strike force was insufficient, he pressed

Ferdinand to make diversions along the Moselle and in Alsace that, as we have

seen in the previous chapter, failed to materialize.

While Spain massed in the south, in the Republic Frederick

Henry staked his political capital on a major blow against the northern

frontier. He was under growing pressure to negotiate. Though he managed to

sideline Adriaen Pauw, the leader of the Dutch peace party, by sending him as

ambassador to Paris in 1636, his support was falling away. The open French

alliance after 1635 split opinion among the Gomarist militants who had been the

war’s principal backers, because Frederick Henry had promised Richelieu he

would accept Catholicism in conquered areas. Moreover, Amsterdam merchants had

no interest in liberating Antwerp, a city that might resume its former place as

the region’s commercial centre. Increasingly, support for the war was

restricted to three groups. The southern provinces of Zeeland, Utrecht and

Gelderland still felt vulnerable and wanted Frederick Henry to capture more

land beyond the Rhine as a buffer. These provinces were also home to the

majority of Belgian Calvinist refugees who hoped military success would enable

them to return home. Finally, there were those who benefited materially from

the war, notably shareholders in the West India Company, an organization that

proved remarkably successful in attracting investors from across the Republic.

These groups were still strong in 1637, but it was significant that the Holland

States implemented the first budget cut since the Twelve Years Truce,

disbanding the most recently raised regiments in the winter of 1636–7.

Frederick Henry seized his chance to attack Breda on 21 July

while the Spanish were still collecting troops on the southern frontier.

Fernando had to march north again. Unable to break the Dutch siege, he tried to

distract the stadholder by taking Venlo and Roermond. His absence enabled

Cardinal de la Valette and 17,000 French to capture Landrecies and Maubeuge,

forcing Fernando to retrace his steps southwards. Breda fell on 7 October,

removing the last of Spain’s gains from its year of victories in 1625.

The Siege

The siege was preceded by an attempt to surprise the

garrison on 21 July 1637 by Dutch cavalry under Henry Casimir I of

Nassau-Dietz. However, the gates were closed in time and the Dutch skirmishers

driven back. The Dutch then from 23 July on first captured a number of villages

around the city (Frederick Henry made his headquarters in Ginneken) and then

started to dig a double line of circumvallation that would eventually reach a

circumference of 34 km. An outer contravallation (8 ft. deep and 16 ft. wide)

defended the besiegers from outside interference, and outside this area the

low-lying countryside was inundated by damming a few rivers. Unlike the

strategy adopted by Ambrosio Spinola at Breda in 1624-5, Frederick Henry did

not plan on a passive siege, aimed at starving the fortress, but intended a

more aggressive approach. The Spanish attempt at relief that the

Cardinal-Infante soon launched was unable to dislodge the besiegers. He

therefore lifted his siege of the besiegers and moved with his army to the

valley of the Meuse, where he took Roermond and Venlo from the Dutch, a

considerable loss.

Undistracted, the besiegers meanwhile started digging

covered trenches inward from the circumvallation line toward the hornworks of

the fortress, which had been constructed by the Dutch themselves on the model

of a star fort. Two of these trenches were dug toward the Ginnekenpoort

(Ginneken Gate), one by French, the other by English mercenaries. The French

finished their work on 27 August, the English one day later. Fascines were used

to fill the moat. The French and English scaled the walls of the hornwork on 1

September. That same night, the French ambassador Girard de Charnacé, who

commanded a French regiment of the besiegers, was adventitiously killed by a

bullet to the head.

The besiegers then started mining the hornwork, and on 7

September the mine was blown, breaching the walls. George Monk, later first

Duke of Albermarle, then a captain in Dutch service, was first in the breach.

The hornwork was taken. However, a few days later a different mine misfired,

and another attack was repelled with great loss of life among the Dutch and

Scottish attackers. Nevertheless, the defenders now abandoned this part of the

outer defense works to the besiegers.

On 2 October, count Henry of Nassau managed to take a

lunette and ravelin and drive the defenders into the city proper. This meant

that the inner city was now open to attack by mines. The garrison knew that the

situation was hopeless. Honor having been preserved, the governor, Gomar de

Fourdin sued for an honorable surrender on 6 October. The capitulation was

signed, and on 11 October the Habsburg garrison left the city with flags flying

and drums rolling. They marched off toward Mechelen.

The defeat prompted Olivares to revert to his Dutch

strategy, instructing Fernando on 17 March 1638 to make a major effort to

compel the Republic to accept reasonable terms in negotiations that were now

reopened. Victory was no longer expected; the aim now was to leave the war with

honour.