By July 1944, the war was turning against the German Reich on all fronts. Ernst Kaltenbrunner, commander (under commander in chief of the SS, Heinrich Himmler) of all SS intelligence operations and head of the Reich Main Security Office, informed the KG 200 operations officer that he needed to provide a plane that could fly almost to Moscow, land and unload cargo and people, all unnoticed. The purpose of that mission, code-named ‘Operation Zeppelin,’ was to kill Josef Stalin. The aircraft chosen for the job was the Arado Ar-232B–a four-engine version of the Ar-232A Tatzelwurm (Winged Dragon)–known as the Tausendfüssler (Millipede) because of the 11 pairs of small idler wheels under the fuselage that were used to land on unprepared fields.

On the night of September 5, two agents, their baggage and their transport were loaded aboard, and the Ar-232B took off. The agents intended to reach Moscow, where they had a place to stay. They carried 428,000 rubles, 116 real and forged rubber stamps and a number of blank documents that were meant to gain them entry to the Kremlin so that they could get close to Stalin.

There was no word from the plane until long past its maximum projected flying time, and it was assumed lost. Then a radio message came from one of the agents: ‘Aircraft crashed upon landing, but all crew members uninjured. Crew has split up into two groups and will attempt to break through to the west. We are on the way to Moscow with our motorcycle, so far without hindrances.’ The two would-be assassins were later captured at a checkpoint when a guard became suspicious of their dry uniforms on a rainy day. Some of the German crew did manage to make it back to friendly lines, but others had to wait until the end of the war to return.

Bizarre schemes and deceptions such as the Stalin assassination plot came from both sides. In October 1944, an agent who had been dropped behind Russian lines suddenly resumed contact with his controller in Germany with an astonishing story to tell. He was in contact with a large German combat group–2,000 men strong–that was hiding in the forested and swampy region of Berezino, roughly 60 kilometers east of Minsk. The Germans, under the command of a Colonel Scherhorn, had been caught behind Russian lines during the Wehrmacht retreat that summer. German intelligence accepted the report as true. KG 200 was dispatched to provide the German troops with supplies that the German high command hoped would allow ‘Kampfgruppe (Battle Group) Scherhorn’ to break out and return to German lines. Not until April 1945 did the Germans learn that ‘Colonel Scherhorn’ was in fact a Soviet operative using the name in an elaborate ruse.

KG 200 was also in charge of the German suicide pilots. The Germans mirrored the Japanese kamikaze efforts with the Reichenberg IV suicide bomb. The concept was developed by a glider pilot who was a veteran of the famous 1940 assault on the Belgian fortress of Eben Emael. As the war turned against Germany and his fellow pilots were slaughtered, he thought that if glider pilots were to be sent to perish, they should be armed with a suitable weapon to bloody the enemy. The Reichenbergs were to be piloted by ‘self-sacrifice men.’ Thousands of men volunteered for vaguely defined ‘special operations,’ and 70 of them were sent to KG 200.

Although these men were trained on gliders, they were to fly a manned variant of the V-1 buzz bomb. The V-1, also known as the Fiesler Fi-103, was already in mass-production for its primary purpose as a flying bomb. The German Research Institute for Gliding Flight at Ainring modified the V-1 to carry a pilot. By 1945, however, the attitude toward using the flying bomb had changed so much that only criminals or pilots who were in a depressed state or were ill would be allowed to fly Reichenbergs.

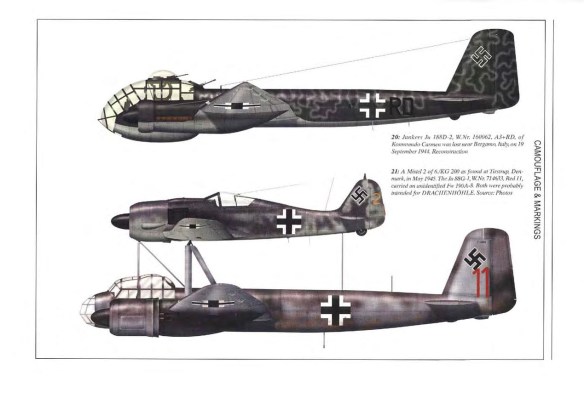

As early as 1942, researchers also began to develop Mistel (mistletoe), a piggyback aircraft–a smaller aircraft mounted above a larger, unmanned aircraft such as a medium-sized bomber. After a series of false starts, the combination settled upon was a Messerschmitt Me-109 or Focke-Wulf Fw-190 fighter atop a Junkers Ju-88 bomber. The machines were joined by a three-point strut apparatus, which was fitted with explosive bolts that would sever the connection when the carrier aircraft–armed with an 8,377-pound hollow-charge warhead in the nose–had been aimed at its target. The warhead would detonate on impact in an explosion that could penetrate 8 meters of steel or 20 meters of ferroconcrete.

By May 1944, the first operational Mistels were delivered to 2/KG 101, a unit closely affiliated with KG 200. The unit was originally slated to attack Scapa Flow in northern Scotland, but the Allied invasion of Normandy changed that plan. On the night of June 24, 1944, Mistels were dispatched against targets in the Bay of the Seine, in the English Channel. Although one of the Ju-88s had to be jettisoned prematurely, the remaining four pilots had successful launches and sank several block ships.

Luftwaffe planners placed all Mistels under the aegis of KG 200 and Colonel Joachim Helbig, an expert Ju-88 pilot. Task Force Helbig was handed a daunting and audacious plan–it had been decided that the Mistels would be used to single-handedly cripple the Soviet war industry. The operation, known as Plan Iron Hammer, was the 1943 brainchild of Professor Steinmann of the German Aviation Ministry, who had pointed out the benefit of raiding selected points in the Soviet infrastructure in order to damage the whole. Iron Hammer was meant to attack the Soviets’ Achilles’ heel–their electrical generation turbines. The Soviets relied on a haphazard system of electrical supply with no integrated grid, which revolved around a center near Moscow that supplied 75 percent of the power to the armament industry. The Germans sought to destroy an entire factory system in one quick blow.

The mission called for KG 200 to launch strikes against power plants at Rybinsk and Uglich and the Volkhovstroi plant on Lake Ladoga. The planes were to drop Sommerballon (summer balloon) floating mines. In theory, a Sommerballon would ride the water currents until it was pulled straight into the hydroelectric turbines of a dam, but the weapon never performed as designed. In addition, the unit soon became short on fuel, and the operation was halted.

Iron Hammer was resurrected in February 1945, with several new twists. The Soviets had overrun all the advance bases included in earlier planning, so the attack would have to be launched from bases near Berlin and on the Baltic. Mistels would now be the primary weapon. Furthermore, Iron Hammer had become a part of a master strategy to regain the initiative in the East. After the strike rendered the Soviet production centers impotent, the Wehrmacht would wait until the Soviets had exhausted their front-line materiel. Freshly rearmed Waffen SS divisions would swarm northward from western Hungary, attempting to drive straight to the Baltic Sea and catch the advance elements of the Red Army in a huge pincer movement. After the Soviets had been eliminated and Central Europe was safe, the Germans would negotiate a separate peace with the Western Allies, and the struggle against Bolshevism could be continued. Iron Hammer was never launched, however. American daylight raiders destroyed 18 Mistels at the Rechlin-Laerz air base. With this main strike force gone, the entire mission was rendered moot even before Iron Hammer was officially canceled.

On March 1, 1945, Hitler appointed Colonel Baumbach to the post of plenipotentiary for preventing Allied crossings of the Oder and Neisse rivers. At his disposal were Mistels and Hs-293 guided bombs. On March 6, an Hs-293 hit the Oder Bridge at Goeritz. The same bridge was attacked two days later by five Mistels escorted by Ju-188 bombers. The Ju-188s scattered air defenses, and the Mistels destroyed two bridges.

These victories and those in following days did little to change the inevitable outcome of the war. KG 200’s remaining pilots and machines were shuffled to various air bases in futile attempts to destroy the Oder bridges. In Berlin, Baumbach was replaced by another officer, who released the KG 200 headquarters group on April 25, 1945. Some men changed into civilian clothes and attempted to reach the Western Allies, while others proceeded to Outstation Olga to continue the fight.

The American advance into Germany forced the relocation of Outstation Olga from Frankfurt am Main to Stuttgart, and then again to the Munich area, where the unit settled inside a Dornier aircraft factory. Stahl and company continued their duty until the situation became untenable. He issued discharge papers and a final service pay and said goodbye to his men.

After the war, the Allies sought out members of the ‘ominous secret group,’ sure that they had been involved in spiriting Nazi officials out of Europe. The continuing mysteries and half-truths about KG 200 prompted Stahl to write KG 200: The True Story, ‘to clear up this business of ‘Hitler’s spy Geschwader.” He also attempts to justify his unit’s record: ‘The fact that not a single former member of KG 200 has ever been accused of any specific misdeed, never mind prosecuted, speaks for itself.’

This article was written by Andrew J. Swanger and originally appeared in the September 1997 issue of World War II magazine. For more great articles subscribe to World War II magazine today!

THEODOR ROWEHL

Prior to the outbreak of World War II, the Luftwaffe conducted a series of aerial photographic flights across Europe in an He-111 twin-engined bomber painted in Lufthansa livery and flown by Theodor Rowehl. A reconnaissance pilot in World War I, Rowehl was renowned for having penetrated British airspace in his Rhomberg C-7. After the war, he had continued to fly a chartered aircraft until he began to supply the newly formed Abwehr with photos he had taken over Poland and East Prussia. Having begun with a single Junkers W-34 based in Kiel, Rowehl soon gathered a group of pilots around him to form an experimental high-altitude flight of five aircraft based at Staaken, but training at Lipetsk, the Luftwaffe’s secret airfield in Russia. His work impressed Herman Göring and he was transferred to the command of Otto (“Beppo”) Schmid, head of the Luftwaffe’s intelligence branch at Oranienburg, to fly specially adapted Heinkel 111s equipped with cameras designed by Carl Zeiss.

Under Rowehl’s leadership, the Luftwaffe’s air reconnaissance wing grew from three squadrons to 53 on the outbreak of war in September 1939, amounting to 602 aircraft, by which time much of Germany’s neighboring territories had been mapped. The organization was divided into 342 short-range aircraft, dedicated to tactical support, and 260 longer-range planes, mainly Junker 88Ds and Dornier 17Fs, undertaking strategic missions.

In December 1943, following the death of his wife in an Allied air raid, Rowehl resigned his command and his unit was renamed Kampfsgruppe 200.