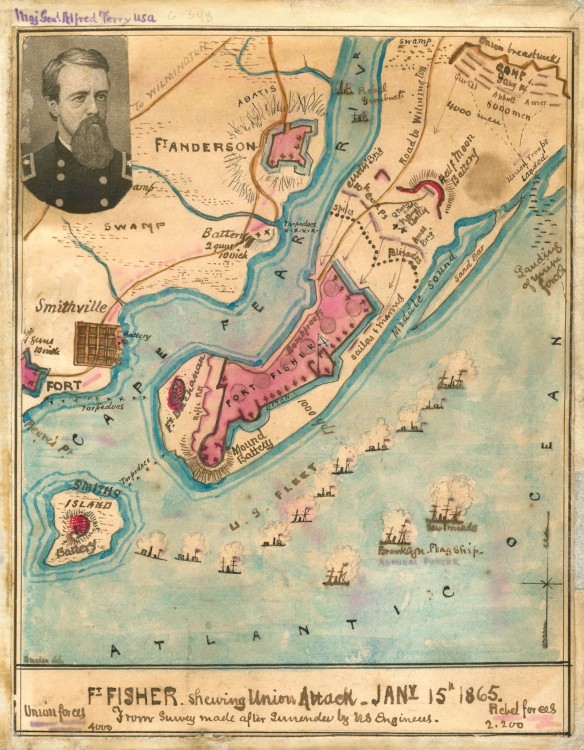

“Union Attack on Fort Fisher, January 15, 1865,” shows area surrounding forts Fisher, Buchanan and Anderson near Smithville, North Carolina. The map shows the Confederate emplacements and forts, and was made by a Union soldier, Robert Knox Sneden, from a survey conducted by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers after the attack.

It was evident that this partnership in command was a dismal failure, and that new commanders must be found if there was to be a second attempt. Porter urged Welles “not to withdraw a single ship” and to try again but with a different general. “If this temporary failure succeeds in sending General Butler into private life, it is not to be regretted,” he wrote. Grant, however, was as disappointed in Porter as he was in Butler, and wanted both men to be relieved. Porter got to keep his job only because Welles came to the defense of his mercurial admiral.

Porter’s new partner would be Major General Alfred Terry, and Grant made it clear to Terry that once his soldiers were on the beach, they were not to stop until Fort Fisher was captured. Grant also urged Terry to establish and maintain good relations with the navy. “It is exceedingly desirable that the most complete understanding should exist between yourself and the naval commander.”

The second Union attack on Fort Fisher

The second Union attack on Fort Fisher began on January 13, 1865. Fifty-nine ships, including four Canonicus -class monitors and the enormous New Ironsides, again hurled tons of high explosives at the sand fort, while Terry’s 9,600 soldiers went ashore in surfboats four miles up the beach. Though Porter still insisted that the first bombardment had been entirely effective, he undermined that argument by completely changing his plan for the second bombardment. Whereas previously each ship had been directed simply to fire in the general direction of the fort using the flagpole as a guide, this time each captain received a chart with red lines on it to indicate which section of the fort was to constitute his special target. Porter also ordered his ships to “fire deliberately,” and “to dismount the guns.” Instead of fi ring as fast as they could load, the gunners watched the fall of each shot and adjusted for the next. It was not only a more carefully planned bombardment, it was also heavier. This time, the navy fired nearly 20,000 shells into the fort.

The other difference during the second attack was the commitment of 2,261 sailors and marines to the land attack. Porter had several times insisted that if only he had been allowed to put his own forces ashore they would easily have captured the fort the first time when the army had balked. When he suggested to Terry the idea of putting a “boarding party” of sailors ashore to assist in the attack, the army general welcomed the idea, though his acquiescence may have been due in large part to his memory of Grant’s orders to get along with the navy.

On Sunday, January 15, 1865, the Union navy ships opened fi re again, blanketing Fort Fisher with tons of explosives and solid shot. This time, the guns in the fort were silenced, one after the other; “only one heavy gun in the southern angle kept up its fire.” Terry and his soldiers, plus Commander K. Randolph Breese, who commanded the landing party of sailors and marines, got in position for the ground attack. At 3:30 p. m., Terry signaled Porter that he was ready, the navy lifted fire, and the attack began. Terry’s soldiers focused on the western salient where Fort Fisher met the Cape Fear River while the sailors and Marines under Breese charged along the sandy beach toward the northeast salient near the coastline. The attack by sailors armed with pistols and cutlasses was ruthlessly shattered. Many were struck down as they crossed the open beach. Others fell as they attempted to scramble up the sloping earthen walls of the fort. Nearly 300 were killed or wounded, and none managed to get inside the fort. Porter’s notion that it was merely a matter of taking possession of an already defeated fort was thus revealed as vanity. Even so, Porter found another rationalization for failure. This time it was the marines who, he claimed, “were running away when the sailors were mounting the parapets.”

Though the sailors’ attack failed, it did distract the fort’s defenders from the real threat, which was Terry’s 9,600 soldiers. They broke through the rebel defenders along the river front and charged into the fort. That did not end the battle, however. The Confederates fought bastion-by-bastion and yard-by-yard as they gave ground grudgingly. Not until 9:00 that night, after almost six hours of fighting, and with 35 percent of the fort’s garrison dead or wounded, did the fort’s commander finally capitulate.

The fall of Fort Fisher closed the port of Wilmington as effectively as Farragut’s charge into Mobile Bay closed that port. Only Galveston, Texas, which had no rail connection with much of the Confederacy, was still open to blockade runners. For all practical purposes, the Confederacy was cut off from overseas supply and support. Within weeks, Robert E. Lee would be forced from his defensive lines around Richmond and Petersburg and begin his retreat westward toward Appomattox Court House.