In the spring of 1915, however, the Allied powers believed that they needed Italian support. Although the Russian government was reluctant to make concessions at the expense of Serbia, the needs of the war took precedence, and Italy was promised almost everything it wished. The agreement was secret, and the terms were not published until the Bolshevik regime came to power in Russia in 1917. The Treaty of London of April 1915 required Italy to enter the war within thirty days. In return for its participation, it was to receive the South Tirol, Trentino, Gorizia, Gradisca, Trieste, Istria, part of Dalmatia, and Saseno and Vlore from Albania. It could also keep the Dodecanese Islands, which had been occupied in 1911, and it was promised a share in any Turkish lands or German colonies that were to be partitioned. In May 1915 Italy declared war on Austria-Hungary, but delayed a similar act in regard to Germany until August 1916.

The next state to enter the war was Bulgaria. The goal remained, as in the past, the recreation of the San Stefano state. The specific objective was thus the acquisition of Macedonian territories, which were in the possession of Greece and Serbia, and the section of southern Dobrudja that Romania had taken in 1913. The Bulgarian decision was of great significance to both sides because of the strategic position of the country in relation both to the Straits and to Serbia, which had not yet been conquered. The Bulgarian action would also influence Greece and Romania, whose ultimate allegiance was still in doubt. In these negotiations the Central Powers held the high cards, since they could offer the Macedonian territory held by Serbia. The Allies could not compete here, nor could they offer compensating land in the possession of Greece or Romania.

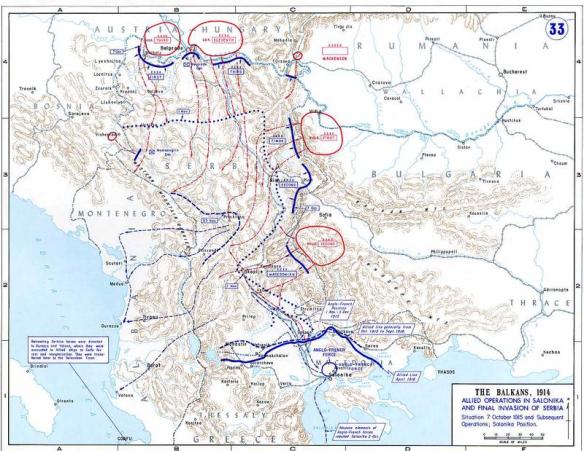

Opinion in Bulgaria was divided on the question of entering the war. A disastrous conflict had just ended. The country was not prepared to fight again so soon. Both the Agrarian Union and the socialists opposed intervention. King Ferdinand and the premier, Vasil Radoslavov, in contrast, were sympathetic to the Central Powers, and the desire for Macedonia was very strong. Obviously, the Allies had nothing to offer. Russia, it was quite clear, would aid Serbia in the future. Under these circumstances, the decision was made to join the Central Powers. In September 1915 Bulgaria signed an agreement by which it was promised Macedonia and, in addition, assured of further territorial acquisitions should Greece and Romania join the Allies. This action sealed the fate of Serbia. In October a major offensive was launched by the German, Habsburg, and Bulgarian armies. In that same month, with the approval of the premier, Venizelos, but not of King Constantine, the Allies landed four divisions at Thessaloniki, but they were unable to move north.

Caught between the invading forces, the Serbian army had little chance. The battle lasted about six weeks. Hopelessly outnumbered, the soldiers attempted to retreat across northern Albania. Marching in winter without adequate supplies through a hostile countryside, the troops suffered huge casualties. Once they reached the Adriatic, they were evacuated by Allied ships to Corfu, where a Serbian government-in-exile headed by Prince-Regent Alexander and Nikola Pasic was established. Montenegro shared a similar fate. In January 1916 a Habsburg army conquered the country, and Nicholas fled to Italy. In this month the Allies were forced also to withdraw from Gallipoli. The Central Powers had thus achieved a commanding position in the Balkans. Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire were allies; Serbia had been subdued. A small Allied army was encamped in Thessaloniki, but it could do little. Under these circumstances the allegiance of Romania and Greece acquired particular importance for the Allies.

Like Italy, Romania in 1914 was linked to the Central Powers through a defensive alliance. It had been renewed five times, most recently in 1913. King Charles favored honoring the commitment, but this opinion was not shared by Ion C. Bratianu, the son of the great minister of the nineteenth century and the most influential Romanian statesman of the period. Pro-French in attitude, he wished to exploit the situation to make gains for his country. In the immediate prewar period, relations between Romania and Austria-Hungary had worsened, primarily because of conditions in Transylvania, whereas those with Russia had improved. In June 1914 Nicholas II had visited the country. The Romanian government could bargain with both sides, and it had much to offer. The army was believed to be strong, and Romanian oil and wheat were in demand by all the belligerents.

The Romanian representatives were, in fact, in an excellent position to negotiate. At the end of July 1914, without consulting its allies, Russia offered Romania the possession of Transylvania in return for remaining neutral. Germany simultaneously promised the acquisition of Bessarabia on similar terms. In a meeting held on August 3, 1914, to discuss the question, the king and a single minister chose to join Germany; the others supported a policy of neutrality. The country was in the favorable situation of having received the assurance that it would obtain either Bessarabia or Transylvania, depending on who won, in return for doing absolutely nothing. Having conceded the major Romanian demands, neither side was left with much to bargain with. Obviously, Russia would not surrender Bessarabia nor the monarchy Transylvania. Nevertheless, during the next months the Romanian government did make some moves in the Allied direction. In October 1914 an agreement was made with Russia that permitted the passage of supplies to Serbia; similar German deliveries to the Ottoman Empire were blocked. In return, Russia conceded both Transylvania and the Romanian sections of Bukovina. Negotiations also continued with the Central Powers, who remained good customers for Romanian wheat and oil. King Charles died in October 1914 and was succeeded by his nephew Ferdinand. This event made easier Romania’s entrance into the war on the side of the Allies.

The Romanian decision, however, did not come until 1916. In June the Russian army launched its last great push for victory, the Brusilov offensive. At first this drive was very successful, and Bratianu feared that if Romania did not enter the war, the government would be at a great disadvantage at the peace table. He, nevertheless, would not move without the assurance of maximum benefits. The Allied powers, who needed Romanian aid, agreed to extensive demands, including the annexation of Transylvania and the Banat up to the Tisza River as far as Szeged, that is, beyond the ethnic boundary and including a large piece of present-day Hungary. Romania was similarly assured of part of Bukovina and participation on an equal basis in the future peace conferences. Having won these promises, the country entered the conflict in August. Its army was to operate in Transylvania; there was no coordination with the Russian command. No sooner had these troops gone into action than the tide turned along the entire eastern front. The Russian offensive failed, and the army commenced a retreat. The Romanian forces in Transylvania and Dobrudja were similarly defeated. In December Bucharest fell into the hands of the Central Powers, and the Romanian government moved to Iaşi.