The major battles of World War I were fought in northern France and along the extensive eastern front. The military decisions were to be reached there rather than in the Balkans, where the campaigns served as a sideshow to the main conflicts waged elsewhere. Therefore this section places more emphasis on the diplomatic negotiations than on the military planning or the actual battles. Despite the fact that final victory depended on the armies of the great powers, these governments throughout the war sought the support of small allies, particularly when it became apparent, as it soon did, that a long war lay ahead. At the beginning of the conflict, the general staffs of the powers had planned on short, decisive campaigns. When these had all failed by the beginning of 1915, and when the western front settled into trench warfare, the leaders on both sides attempted to win the assistance of the Balkan countries, which occupied strategic locations and had respectable armies. The Balkan governments, with the exception of the Serbian, which was already at war, thus found themselves courted by the belligerents, and they used the opportunity to bargain for the maximum advantages. Each nation also wished to make certain that it would choose the winning side.

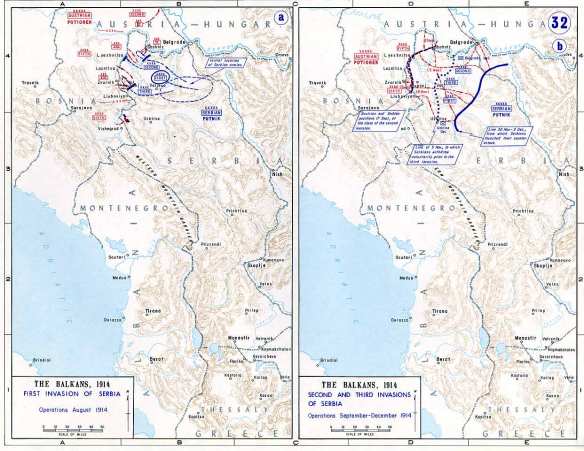

At the beginning of the war Serbia was in a very dangerous position in both a military and a political sense. Although the government had hoped to avoid a conflict, this state of 4.5 million found itself fighting an empire of 50 million. It had powerful allies, but they were far away and chiefly concerned with defending their own frontiers against a German attack; they had no troops or arms to spare for Serbia. It was generally expected that the Habsburg army would quickly be victorious. Instead, the first successes were on the Serbian side. The army was, in fact, able to repel two attacks in 1914 and even to go on the offensive and enter Habsburg territory. The Russian advance into Galicia forced the monarchy to shift troops to this zone. Moreover, the Serbian soldiers had gained experience in the Balkan Wars, and they fought well. In early December they suffered a reversal and Belgrade was taken. They then won a major victory on the Kolubara River and in mid- December regained Belgrade. The Serbian losses during the fighting were extremely high. The government had no way of replacing these men or of acquiring more military supplies. Not only were immense casualties suffered by the army in the battles, but a serious typhus epidemic hit the country. Despite the military achievements, the future looked bleak.

The previous Habsburg doubts about the loyalty of their national groups in war soon proved unfounded. The South Slavs, as well as the majority of all the nationalities, fought bravely. Measures of control and repression were, of course, introduced in the monarchy, as in all of the belligerent states. Newspapers were closed, and suspected traitors were imprisoned. Some acts of resistance occurred, but nothing like the French army mutinies of 1917 or the wholesale desertions of the Russian forces at the time of the revolution. Until the last months of the war, the empire held together. In fact, some parties, such as the conservative and clerical parties in Croatia and Slovenia, supported a war against Orthodox Serbs. Even the Serbian detachments of the Habsburg army remained loyal to the traditions of the Military Frontier. Among the troops that launched the attack on Serbia in August 1914, some corps consisted of 20 to 25 percent Serbs and 50 percent Croats. A contemporary Yugoslav historian writes:

In the battle of Mackov Kamen in September 1914, fighting on one side was the Fourth Regiment of Uzice [Serbian] and on the other a regiment from Lika including a large number of Serbs from that area whose forebears had for centuries been the most faithful soldiers of the Habsburg emperors. Commander Puric of the Uzice regiment led his men in fourteen charges, to which the men from Lika responded with lightning-like counter-charges. In one of these Puric shouted to them, “Surrender, don’t die so stupidly, and they replied, “Have you ever heard of Serbs surrendering”

Such romantic national traditions were to yield high casualty figures on all sides.

After the beginning of the war the first state to come to a decision about its allegiance was the Ottoman Empire. Under the influence of Enver Pasha, the pro-German minister of war and one of the most influential of the Young Turk leaders, the government signed a secret alliance with Germany on August 2, 1914, the day before Germany declared war on France. Although the Porte did not immediately enter the fighting, it did offer sanctuary to two German warships, the Goeben and the Breslau, which it claimed to have purchased. In November the empire was formally at war with the Allies. With the closure of the Straits to Allied shipping, sea communications between Russia and its Western partners were effectively severed. In an effort to remedy this situation and to improve the Allied military position in the Near East, the British government adopted a controversial plan to attempt to open the Straits. The responsibility for the action was largely that of Winston Churchill, who at that time was first lord of the Admiralty. The Dardanelles and Gallipoli campaigns were military disasters, and they were extremely damaging to the career of that politician. In the first effort, carried out in February 1915, a squadron of eighteen British warships tried to force its way through the Straits. After four ships were lost, the commander ordered a withdrawal. In fact, had he pressed on, he might have won a victory, since the Ottoman forts had run short of ammunition. The Gallipoli campaign had even worse results. The objective was to secure a land base from which attacks could be launched on the Ottoman Empire. Allied troops were able to take a beachhead, which they held from April 1915 to January 1916. Ottoman forces remained entrenched on the heights above the Allied soldiers, whose losses, particularly among the Australian and New Zealand contingents, were immense.

The Allied failure at the Straits was balanced by the entrance of Italy into the war in May 1915. Although this state had been a member of the Triple Alliance, the terms of the treaty were defensive. This fact, together with the failure of the Habsburg Empire to keep Rome informed of its intention to attack Serbia, gave the Italian government ample excuse to remain neutral. It could therefore bargain with both sides and sell its support to the highest bidder. Italian national aims were quite extensive; they included the South Tirol, Trentino, Trieste, Gorizia, Gradisca, Istria, most of Dalmatia, and some Albanian territory, in particular the island of Saseno (Sazan) and the port of Vlore. Needless to say, these lands had a majority of Albanian, South Slavic, and German people. In the negotiations the Allies had a great advantage because they could freely use Habsburg territory to satisfy Italian demands. The Habsburg representatives could offer only Trentino in return for neutrality. The Allied governments were, however, hampered to an extent by the problem of the South Slav territory. The war had commenced ostensibly to save Serbia. If Italy received the Dalmatian coast, Serbia would not gain the outlet to the sea that was a major war aim. Moreover, if Italy acquired Dalmatia and Istria, it would have under its control about 700,000 South Slavs. Such problems caused difficulties mainly in Britain, where war propaganda was conducted with a high moral tone.