It was just now that the Fifth Battle Squadron reappeared on the scene, finally overtaking both Beatty and Hipper. It was a timely intervention for Beatty: while there was something approaching parity between the lighter German guns versus the thinner British armor and the heavier British guns versus the better-protected German ships, Hipper’s battlecruisers could not stand up to the 15-inch guns of the four Queen Elizabeth class battleships. At 19,000 yards, more than a mile beyond the maximum range of the German guns, Evan-Thomas’s ships opened fire.

The Germans recognized their unmistakable silhouettes and knew what was coming. Georg von Hase, Derfflinger’s gunnery officer, remembered how:

Behind the [British] battlecruiser line appeared four big ships. We soon identified these as the Queen Elizabeth class. There had been much talk in our fleet about this class…. They fired a shell more than twice as heavy as ours. They engaged at portentous ranges.

Endless drills and target practice had produced gunnery in these four dreadnoughts that was among the best in the Grand Fleet. They quickly found the range.

The first German ship to feel the Fifth Battle Squadron’s fire was von der Tann. At 1410 she took a hit aft, the 1,920 pound shell tearing through her armor belt, allowing 600 tons of seawater into her hull. Even the near-misses were punishing, as the explosions shook the ship from stem to stern. All four of the Fifth Battle Squadron’s ships were within range, allowing Barham and Valiant to shift their fire to Moltke, while Warspite and Malaya engaged von der Tann. A shell from one of them punched through Moltke’s side armor and detonated in a starboard coal bunker, setting off a coal dust explosion, which wrecked one of her 5.9-inch guns.

Hipper ordered his ships to begin zigzagging in order to throw off the British gunnery, even though he knew it would affect his own squadron’s shooting. Von der Tann was close to being overwhelmed, as she was the target of not only Warspite and Malaya, but New Zealand as well. At 1617 the British battlecruiser put a shell into the German ship’s forward 11-inch turret, jamming both guns and flooding the magazine. At the same time a 15-inch shell striking aft plunged through von der Tann’s armored deck and knocked out her rear turret. Her remaining two turrets continued to fire, though, scoring a hit on New Zealand in return, although the damage was slight and there were no casualties.

At the head of the two columns, however, one of the most spectacular incidents of the entire battle was about to unfold. Because of faulty British gunnery distribution reminiscent of Dogger Bank, Derfflinger found herself completely unengaged by any of Beatty’s ships. Both she and Seydlitz concentrated her fire on Queen Mary, and before long the accuracy of their shelling extracted an awful toll.

Queen Mary had already been hit several times by this point, with her aft secondary armament wrecked; at least one 11-inch shell had landed near X turret. Observers on Seydlitz saw an ammunition fire flare up in Queen Mary’s after superstructure near the ruined 4-inch battery. Q turret then took a hit that put the right gun out of action, and five minutes after that two shells landed simultaneously on Queen Mary. One hit the left gun of Q turret, breaking it in two, the other seemed to strike somewhere between A and B turrets. According to Midshipman Jocelyn Storey, who was stationed in Q turret,

A heavy shell hit our turret and put the right gun out of action, but killed nobody. Three minutes later an awful explosion took place which smashed up our turret completely. The left gun broke in half and fell into the working chamber and the right one came right back. A cordite fire got going and a lot of the fittings got loose and killed a lot of people.

Petty Officer Ernest Francis, whose battle station was in X turret heard more shells crash into Queen Mary, then there was a sudden, eerie silence; in his words, “Everything in the ship went as quiet as a church.” Francis immediately sensed that something was wrong and, looking out a hatch at the back of X turret, saw that the after superstructure was a shambles and the ship was taking on an ominous list to port. A and B turrets’ magazines had blown up.

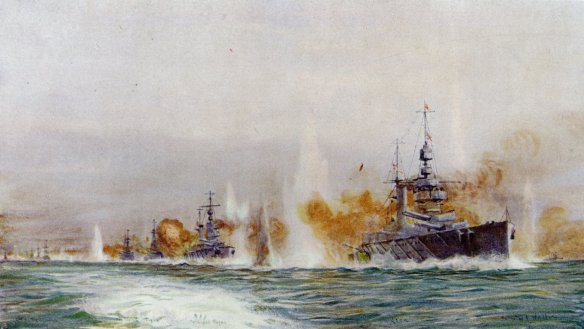

The British battle cruiser Queen Mary exploding. There is a Lion-class ship to the left.

Queen Mary’s back was broken and the fore part of the ship beyond the forward funnel had already gone under. Von Hase in Derfflinger watched

as a vivid red flame shot up from her forepart. Then came an explosion forward, followed by a much heavier explosion amidships. Black debris flew into the air and immediately afterward the whole ship blew up with a terrific explosion. A gigantic cloud of smoke rose, the masts collapsed inwards, the smoke cloud hid everything and rose higher and higher. Finally nothing but a thick, black cloud of smoke remained where the ship had been. At its base the cloud covered only a small area, but it widened toward the summit and looked like a monstrous pine tree.

An officer on the bridge of Tiger, only five hundred yards astern of Queen Mary, saw much the same thing as did von Hase:

I saw one salvo straddle her. Three shells out of four hit…. The next salvo straddled her and two more shells hit her. As they hit, I saw a dull red glow amidships and then the ship seemed to open out like a puffball…. There was another dull red glow forward and whole ship seemed to collapse inwards. The funnels and masts fell into the middle, the roofs of the turrets were blown a hundred feet high….

A passing gust of wind parted the smoke cloud, and, as they passed, Tiger and New Zealand were able to see all that was left of Queen Mary. Only the stern of the ship was afloat, listing hard to port, her screws out of the water and still turning. New Zealand’s gunnery officer reported seeing men crawling out of the after turret and along her decks, and just as New Zealand was passing by, what remained of Queen Mary suddenly rolled over and blew up. Out of a crew of 1,275, there were nine survivors.

The loss of Queen Mary left Beatty stunned. He had engaged Hipper fully confident of his numerical superiority of six battlecruisers to the German five. Now within the space of three quarters of an hour he had lost two of them. No sooner had the report of Queen Mary’s destruction reached him than Princess Royal was engulfed in a torrent of shell splashes that completely hid her from view, and a signalman on Lion’s bridge reported in dismay, “Princess Royal blown up, sir!” Nonplussed, Beatty turned to Captain Chatfield and blurted out, “There seems to be something wrong with our bloody ships today!” Just then Princess Royal steamed out of the splashes, smoke, and spray and spat a broadside at Moltke.

It was at this moment that an ad hoc flotilla of British destroyers, a dozen in all led by Commander Edward “Barry” Bingham in Nestor, finally caught up with the battlecruisers, and Beatty immediately ordered them to attack Hipper’s squadron with torpedoes. What happened next was so confusing that no two eyewitness accounts agree on more than the most general outline of events. The British destroyers charged toward Hipper’s battle line at 34 knots, only to be met by the light cruiser Regensburg and 15 German destroyers. A free-for-all quickly ensued as the little ships dodged and weaved back and forth, narrowly missing one another, 3- and 4-inch guns barking and banging, torpedoes hissing out of their tubes; the secondary batteries of the battlecruisers joined in whenever an enemy destroyer was careless enough to come within range. The German destroyers managed to launch 18 torpedoes at the British battlecruisers; the British destroyers launched 20. Both battlecruiser squadrons turned away from the torpedo attacks, and all 38 missed, save for one, which managed to find its way into Seydlitz’ port side.

Seydlitz was rapidly acquiring the reputation for being at once the unluckiest and the luckiest ship in the High Seas Fleet—unlucky in that she seemed to attract enemy shells and torpedoes and lucky in that they never caused enough damage to sink her. Severely damaged at Dogger Bank, she had come within a few seconds of blowing up, but escaped, though with the loss of almost 90 crew. Here at Jutland half of her guns were already out of action, and she was badly holed above and below the waterline, though she was able to maintain her position in the German battle line. Now a British torpedo exploded close to A turret, tearing a hole 40 feet long and 13 feet wide in her hull plating. Still she was able to maintain her position, but her situation grew increasingly perilous as hundreds of tons of seawater began flooding her forward lower decks.

This sort of success came at a price, however, as the destroyers Nomad and Nestor—the latter Bingham’s own ship—both took hits in their boiler rooms, leaving them powerless and sinking, wallowing helplessly between the two fleets. The British exacted measure for measure, however, as the German destroyers V-27 and V-29 were sunk in the melee.

Though only one British torpedo found its mark, the attack by Bingham’s destroyers had bought time for Beatty. It was desperately needed, for the tactical situation had been utterly transformed, and now the British battlecruisers were suddenly faced with a far greater threat than any Beatty had ever imagined. He had been lured toward a German trap.

At 1638 Hipper’s squadron unexpectedly made a 180 degree turn to port and began steaming northward again. At first Beatty had no idea why the Germans had turned about. There is no denying that for the first hour of the Battle of Jutland the Royal Navy came off second-best. Not only had the Germans sunk two of the British battlecruisers, they had inflicted serious damage on three of the survivors, and while some of them had taken significant damage— Seydlitz was, in fact, already in serious trouble and von der Tann was reduced to a single working turret—yet turning back into the North Sea would simply prolong the engagement, increasing the likelihood that one or more of Hipper’s ships would join Indefatigable and Queen Mary on the bottom. A signal received by Lion at the same moment Hipper turned suddenly made it all clear, laying bare the German admiral’s stratagem as well as his masterful execution of it.

For Hipper had performed his reconnaissance and entrapment role to perfection: he had lured Beatty far enough to the south for Scheer’s dreadnoughts to be able to bring their guns to bear. While the British battlecruisers might face their German counterparts as more or less equals, they were never designed to stand up to the German battleships. It was to be the culmination of Scheer’s strategy of catching a section of the Grand Fleet unawares and destroying it in detail, simultaneously erasing the Royal Navy’s numerical superiority and dealing a psychological blow from which the British fleet—and, indeed, the British people—might never recover.

The signal delivered to Lion’s bridge at 1638 was from the light cruiser Southampton. It read, “URGENT. PRIORITY. Have sighted enemy battlefleet, bearing approximately southeast.”

When Beatty had turned his force to the south and formed the battlecruisers into a line of battle at 1545, the 12 ships of his three light cruiser squadrons increased speed, straining to take up their proper scouting positions in front of the battlecruisers. By 1635 they had overtaken the big ships and were again acting as an advance screen, pounding southward at better than 28 knots. Standing on the bridge of HMS Southampton, flagship of the Second Scouting Squadron, Commodore William Goodenough looked off to the southeast and watched in amazement as the pale grey battleships of the High Seas Fleet, along with a horde of escorting cruisers and destroyers, emerged from the North Sea mist. “We saw ahead of us first smoke, then masts, then ships,” he later wrote, “sixteen battleships with destroyers around them on each bow.” Goodenough waited a few moments before sending out a signal alerting the rest of the British fleet to the High Seas Fleet’s presence, wanting to be sure of his sighting. Then his commander (the Royal Navy’s equivalent of the U.S. Navy’s executive officer) cooly reminded him, “Sir, if you’re going to make that signal, you’d better do it now. You may never make another.”

It was not an idle comment—Goodenough’s four cruisers were already within range of the German dreadnoughts’ guns. The only thing that saved them from annihilation was a case of mistaken identity: seen from bowson, the British cruisers were mistaken for German ships and were momentarily spared an onslaught of 11- and 12-inch shells. At 1638 Goodenough’s first sighting report went out to the British fleet.

Still Goodenough pressed closer, wanting to gather as much information as he could, until the range was down to barely 13,000 yards—6.5 miles, almost point-blank range for a battleship’s guns. Finally, at 1648, he ordered his ships to turn away, and as the four-funneled profiles of the British cruisers were exposed, Scheer’s battleships opened fire on them. Desperately twisting and turning, dodging salvos by turning into the shell splashes of the previous shot, Goodenough was able to make his escape, all the while transmitting to Beatty and Jellicoe what he had learned. “URGENT. PRIORITY. Course of enemy’s battlefleet is north, single line-ahead. Composition of van is Kaiserclass…. Destroyers on both wings and ahead. Enemy’s battlecruisers are joining battlefleet from the north.” The trap for Beatty had been set. The question now was whether or not he would fall into it.