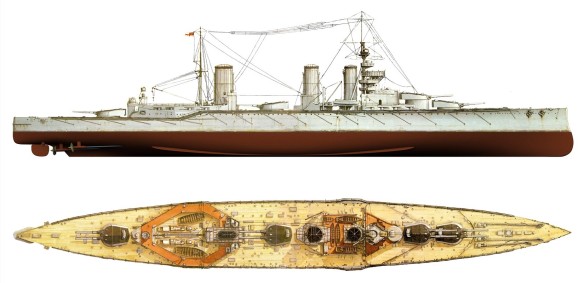

The HMS Queen Mary launched in 1912 was the last British battlecruiser built before the outbreak of the First World War. Being the sole member of her class, the HMS Queen Mary shared most part of features with the battlecruisers of the Lion class, including her eight 343 mm guns; she differed from them in the distribution of her secondary armament and armour, and in the location of the officers’ quarters (every capital ship since the HMS Dreadnought launched in 1906 had placed the officers’ quarters closer to their action stations amidships, but after complaints, the HMS Queen Mary was the first battlecruiser to restore the quarters to their traditional place in the stern, and in addition, she was the first battlecruiser to mount a sternwalk). The HMS Queen Mary participated and was sunk in the Battle of Jutland in 1916, where she was hit twice by the German battlecruiser Derfflinger, which caused her magazines to explode shortly afterwards.

As he stood on the bridge of HMS Lion, gazing resolutely through his glasses at the approaching German battlecruisers, David Beatty could hardly believe his luck. This was Dogger Bank all over again, but this time he possessed two distinct advantages that he had lacked in the earlier battle: the Germans were much farther from the safety of the Heligoland, and Beatty had the advantage of numbers. With Hugh Evan-Thomas’s Fifth Battleship Squadron added to his fleet, he had twice as many ships as the German battlecruiser squadron, and with the addition of the four Queen Elizabeth’s 15-inch guns, he had almost three times the weight of shell as the Germans. And while the German battlecruisers were swift, their British counterparts were faster still: they would become anvil to the four Queen Elizabeth’s hammer; the enemy ships would be pounded to pieces. There would be no escape for Franz Hipper this time.

As he stood on the bridge of SMS Lützow, gazing resolutely through his glasses at the approaching British battlecruisers, Hipper could hardly believe his luck. This was Dogger Bank all over again, but this time he possessed one distinct advantage that he had lacked in the earlier battle: he knew for certain that this time the main German battle fleet was coming up behind him in support. Soon he would have the advantage of overwhelming numbers and weight of shell, and even the presence of the four fearsome Queen Elizabeths of the Fifth Battleship Squadron would not be enough to save the British battlecruisers from being methodically pounded to pieces. His battlecruisers would be the anvil to the High Seas Fleet’s hammer. There would be no escape for Beatty this time.

Almost simultaneously Beatty and Hipper each gave the order “Action Stations” and “Clear for Action”; bugles began sounding and drums beating, sending officers and ratings alike scurrying to their posts. Deep within the ships the “Black Gangs” of the boiler rooms began stoking the fire grates to increase speed. High above the decks of the battlecruisers, in the fire-control positions, gunnery officers were busy manipulating rangefinders and plotting tables, calculating ranges and bearing in order to work out the bearing and elevation figures passed down to the gun turrets.

Inside the gun turrets of both British and German ships, an intricate ballet was taking place. To an outside observer it would have seemed a chaotic amalgamation of shouts, moving men and machinery, mechanical clanks, clangs and rattles, and the intermittent ringing of bells. However, each movement of man and machine was carefully choreographed, practiced over and over again in countless drills, until the men worked as smoothly and methodically as the machines they served.

In their excitement, the magazine crews of some of the British battlecruisers were sowing the seeds of their own destruction: knowing that reducing the time between salvos improved the chances of their ship’s guns getting hits on the enemy, they resolved to do their best to reduce that time to a minimum. In order to speed up the movement of propellant charges to the guns, cordite bags were stacked in the shell handling rooms and the magazine lobbies, while the flash doors were left open, eliminating the vital seconds necessary to repeatedly close them and open them again each time a shell or powder charge was passed through. Though they had no way of knowing, thousands of them would pay for their enthusiasm with their lives.

For some reason, though the British battlecruisers actually sighted their enemy counterparts first, almost ten minutes passed before they opened fire on the German ships. While this was far from the only tactical mistake Beatty made that afternoon, it was one of the worst, for he gave up the advantage the superior range his 13.5-inch guns gave him. The maximum range of the 12- inch guns mounted on Lützow and Derfflinger was only slightly more than 17,000 yards, 5,000 yards short of the maximum range of the 13.5-inch guns carried on Beatty’s four “Big Cats”; the maximum range of the German 11- inch gun was shorter still. In other words, there was a 2.5 mile difference between the maximum range of the German guns and those on the British ships. In his haste to close with the enemy, Beatty surrendered this potentially devastating tactical advantage, for with the combination of superior speed and range, he could have dictated the conditions of the battle, keeping well outside of the reach of the German guns while pummeling the German battlecruisers almost at will.

It was a tactical lapse that Beatty could never fully explain, then or later. It was not a question of ignorance: even in the days of fighting sail, the captain of a more heavily armed ship often sought the “zone of immunity,” ranges where his guns could strike his opponent without fear of being struck by the enemy’s smaller, lighter, and shorter-ranged guns. However, because the smaller ship was almost invariably the faster, a commander who found himself outgunned could choose to sail out of range entirely, use his speed to shorten the range until his own guns could reply effectively, or maneuver into positions where the enemy’s heavier guns could not be brought to bear. But in Beatty’s case, he not only had the advantage of larger, longer-ranged guns, he also had superior speed, which by careful maneuvering should have allowed him to keep Hipper in a position where the German battlecruisers were under constant bombardment without ever being able to make any sort of effective reply.

The most likely explanation is that Beatty’s natural aggressiveness—never a fault in the eyes of the Royal Navy—blinded him to this opportunity. Having twice watched the German battlecruisers escape, he was determined to close with Hipper and at the same time place his own ships between the Germans and their home port, compelling the German battlecruisers to fight. Beatty chose a course for his squadron that converged upon the Germans, rather than merely paralleling them, giving up the range advantage in order to ensure a battle.

This suited Hipper perfectly, for he well knew the difference in range between the British 13.5-inch guns and his own 11-inch and 12-inch weapons, so closing the range between the battlecruiser squadrons actually worked in his favor. At 1545, when the range had dropped to 16,000 yards, he calmly gave the order to open fire. Lützow’s first salvo roared out, followed an instant later by the guns of Defflinger, Seydlitz, Moltke, and von der Tann.

On the bridge of Lion, Beatty’s officers waited anxiously for the order to begin firing to be given, but Beatty was busy dictating a signal to John Jellicoe. Captain Ernle Chatfield sent word to the admiral that the range was closing rapidly but received no reply. After a few more moments passed, Chatfield decided he could wait no longer and told his gunnery officer to open fire. A four-gun salvo crashed out, almost at the same instant that a ripple of fire ran down the German battle line.

The opening German salvoes were impressive, accurate, and tightly grouped. The first shots fell short by a mere 200 yards; the second salvo straddled Tiger, two of the four shells hitting her, the crash of tearing metal being clearly heard on the other British ships over the sound of the exploding shells. Beatty held his course for another five minutes, until the range was down to 13,000 yards, and then ordered the squadron to turn one point to starboard, bringing the British ships onto a parallel course with the German battlecruisers.

Now the two squadrons began to slug it out in earnest as they steamed southward at a speed of nearly 26 knots. On the bridge of each warship the captain and his staff were watching the enemy fleet, observing the fall of their own shells as well as the enemy’s. A signal officer, usually a junior lieutenant, was standing by, ready to carry any messages that his captain might wish to send to the flagship or other ships in the squadron; he was equally prepared to pass along any messages received. A signaler, either a senior seaman or a midshipman known for his keen eyesight, was posted with a telescope continually trained on the flagship, watching for signals to be hoisted. Range and bearing information was continually passed down from the spotting officers in the fighting tops, along with reports from various parts of the ship concerning casualties or damage. Blast and smoke from the guns washed across the deck, spray from the sea blew in the officers’ faces, while often mugs of tea or coffee, sometimes laced with rum, were passed out among them. It was a scene of masterful calm and organization, yet underneath it all was the constant awareness that at any given moment, oblivion could overtake it all in a blinding flash of flame and crash of thunder as an enemy shell obliterated their position.

Broadsides bellowed out between the German and British squadrons, as Hipper’s ships quickly found the range and began straddling Beatty’s battlecruisers almost immediately. British gunnery left a lot to be desired in the opening salvos, some groupings passing more than two miles beyond their targets. HMS Tiger’s gunnery was particularly appalling, a fact that Beatty later attributed, not without some justification, to the fact that a disproportionate number of her crew was made up of defaulters and apprehended deserters.

Further aggravating the problem was that at the outset of the action Beatty was denied the guns of the Fifth Battle Squadron, commanded by Rear Admiral Hugh Evan-Thomas, one of the best-shooting squadrons in the whole of the Grand Fleet. Here a signaling error was to blame, though for once Beatty’s flag lieutenant, Ralph Seymour, was not responsible. Evan-Thomas’s squadron was positioned five miles off Lion’s port bow, a long distance for signaling by flag hoists; because of this Tiger was detailed with the responsibility of passing any signals made by Lion to Evan-Thomas’s flagship Barham by searchlight. When Beatty gave the order for the Battlecruiser Squadron to turn to the southeast, Tiger failed to pass the signal along, and the Fifth Battle Squadron continued along its northerly course. Barham’s captain, A.W. Craig, urged Evan-Thomas to follow Lion’s lead, but the admiral declined, believing that Beatty would have specifically signaled if he wanted the battleships to follow. Nearly seven minutes passed before Beatty noticed that the four battleships had not followed the battlecruisers and instructed a recall signal to be sent by searchlight to Evan-Thomas. By then the Fifth Battle Squadron had drawn off nearly ten miles from the British battlecruisers and was hard-pressed to catch up.

Though Tiger was the first British ship to be hit, the most serious of the early blows struck by either side was a shell that burst on the top of the left gun of the Lion’s Q turret, the blast peeling back the roof and front as though it were a sardine tin, killing most of the gun crew outright. A fire sprang up among the red-hot wreckage, and soon propellant charges began to burn as the wind, whipped up by the ship’s speed, blew through the devastated turret. Flames began reaching out toward the turret trunk, which led to the shell handling rooms below decks and from there to the magazine, where some 400 tons of 13.5-inch shells were stored. Should the fire reach it, the magazine would explode, destroying the ship. Q turret had been manned by the Royal Marines under Major Francis Harvey, and it was in this moment that the Major added another page to the “Bootnecks” legacy of heroism. In shock, bleeding profusely from the stumps of both legs—they had been blown off in the explosion—Harvey dragged himself over to the speaking tube that led down to lower decks and with his dying breath shouted for the magazine to be flooded. It was just in time: when the magazines were reopened after the battle, the crews were found with their hands on the door clips—they had died in the act of securing them. The fire continued to burn for some time, but the magazines were safe and the ship was saved; Lion never left her place in the battle line. Major Harvey was honored with a posthumous Victoria Cross.

Yet such was the fury of the bombardment the two squadrons of battlecruisers were unleashing upon each other that the destruction of Q turret went unnoticed on Lion’s bridge until the marine sergeant, bloody, his uniform singed, a stunned expression still on his face, appeared. Approaching Lt. William Chalmers, he announced in the curiously calm tones of those still in the grip of shock, “Q-turret has gone, sir. All the men were killed and we’ve flooded the magazines.” At this, every head on Lion’s bridge swiveled toward the young man, then turned to look aft. “No further confirmation was needed,” Chalmers later wrote, “the yellow smoke was rolling up in clouds from the gaping hole, and the guns were cocked awkwardly. All this had happened within a few yards of where Beatty was standing and none of us on the bridge had heard the detonation.”

That was hardly surprising: during the first quarter hour of their gunnery duel, Hipper’s ships had scored as many as a dozen hits on Beatty’s battlecruisers. Salvos were crashing out from the muzzles of the guns of both squadrons with almost clockwork regularity. With the constant roar of the guns in their ears and their attention tightly focused on the German warships, it is hardly surprising that Beatty and his staff did not take immediate notice of Q turret’s devastation.

Four of Beatty’s six ships took multiple hits within the first 15 minutes of the action. In addition to the devastating strike on her Q turret, Lion took three other hits, all apparently from Lützow. Likewise Tiger was hit multiple times by Moltke; Princess Royal was struck by two shells from Lützow and Queen Mary by Seydlitz. Only Indefatigable and New Zealand seemed immune.

Not that Hipper’s ships were getting away unscathed. The British battlecruisers quickly corrected for their embarrassing overshoots in the opening minutes of the battle, and within minutes were scoring powerful hits of their own. At 1555 a shell from Queen Mary exploded in Seydlitz’ battery deck, while Lion scored two hits on Lützow at about this same time, and Derfflinger was hit once. A near-miss from a shell fired by Tiger at Moltke shook the entire ship, jarring fittings loose and creating electrical problems. Seydlitz then took yet another hit from Queen Mary, which crashed into the German battlecruiser’s forward midships turret, putting it out of action for the remainder of the battle. Moments later, a near-miss along Seydlitz’ starboard side buckled her armor belt for almost 40 feet, causing flooding in several compartments.

Astern of them, von der Tann and Indefatigable, each the oldest battlecruiser in its respective squadron, were having their own private gunnery duel, each ship having fired nearly 50 shells at the other. At 1602, a salvo from the von der Tann came crashing down on Indefatigable. The British ship staggered out of the battle line—whether by accident or as an intentional course change no one would ever know—with smoke pouring from her stern, but before she could give any indication of the extent of her damage, another shell hit her near A turret, and yet another hit the turret itself. For some seconds she seemed unhurt by these last two but then she blew up violently, rent by sheets of orange flame and shrouded in billows of brown cordite smoke. The exploding shells had either ignited the cordite charges inside the turret trunk, and the flash fire passed down to the magazines, or the shells themselves penetrated the armor over the battlecruiser’s magazines and exploded inside. Whichever was the case, the results were catastrophic: Indefatigable was torn apart in a single tremendous blast.

Signaller Charles Falmer, whose action station was in the foretop, remembered that moment with startling detail:

There was a terrific explosion aboard the ship, the magazines went. I saw the guns go up in the air just like matchsticks—12-inch guns they were—bodies and everything. She was beginning to settle down. Within half a minute the ship turned right over and she was gone.

Posted in the forward topmast, 180 feet above the water, Falmer was thrown clear of the sinking ship as she rolled over onto her starboard side and then went under in less than a minute. Only Falmer and one other crewman survived; 1,017 died with Indefatigable.

With the loss of Indefatigable and Evan-Thomas’s Fifth Battleship Squadron still not yet within range, the two battlecruiser fleets were now evenly matched in numbers. Lion was hit by five shells from Lützow, one of them carrying away her transmitting aerial, leaving Beatty with no means of contacting his ships or Jellicoe directly by wireless—Lion could receive signals but not send them. There was neither the time nor the opportunity for Beatty to shift his flag to another ship, so he resorted to the awkward alternative of sending signals via flags or searchlight to Princess Royal, who then passed them along via wireless. Beatty needed time to reassert control over the situation and so ordered the squadron to alter course a point to starboard, opening the range to 18,000 yards. For the moment the guns on both sides fell silent.