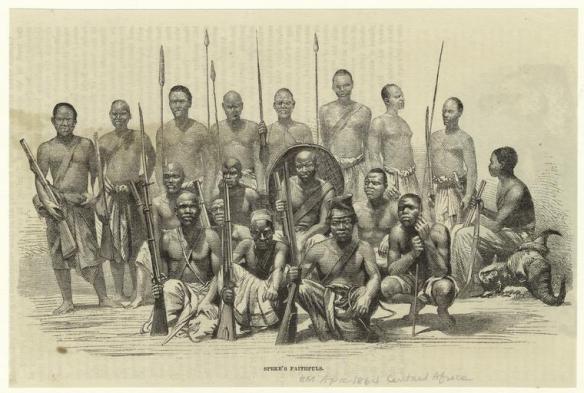

These Swahili of the East coast of Africa supplied most of the troops for the Arabs from Zanzibar and, indeed, those who had settled further into the interior. They also worked for European explorers and this picture of Speke’s “faithfulls” gives a good idea of their appearance.

The greatest challenge faced by the Force Publique in its early years came in the 1890s, in the so-called “Arab wars”.

The sharpest struggles were those that had to be undertaken not against the Africans, but against Swahili slave traders (often called “Arabs” but rarely of pure Arab descent) and their followers in the eastern Congo.

The Congo Arab war was one of the bloodiest conflicts of the whole era of imperial conquest.

The fighting [was] massive, because both sides enlisted the aid of thousands of irregulars. An estimate of 70,000 dead on the Swahili–Arab side is probably exaggerated, while figures for Congo State losses are not available. At all events, tens of thousands died in this campaign.

The Congo Arab war also was (and remains) one of the most obscure of the wars of imperial conquest in Africa. Fought over enormous distances far from the centres of European authority, it was difficult for even Free State officials to follow the action, and it excited relatively little attention abroad. Nor has the war been the subject of many recent studies, even in Belgium or Congo. There is, for example, no good biography of the commander of the Free State forces, Commandant Francis Dhanis, who was made a baronet for his services during the conflict.

What is clear, however, to even the most casual observer is that the crucial factor in the eventual success of the Free State forces was their control of the waterways of the eastern Congo, an advantage gained thanks to the foresight of Henry Stanley. A glance at the map, for example, shows that the main population centres of the Arabs, principally the areas around the towns of Nyangwe and Kasongo on the Lualaba River downstream from Stanley Falls, were easily accessible to the Free State’s river fleet. In anticipation of war with the Arabs, the Force Publique had moved to strengthen this advantage by building heavily fortified riverine bases at the edge of the Arab zone, at Basoko down the river from Stanley Falls and at Lusambo directly to the south on the Sankuru river. The fort at Basoko, with a garrison of 300 men, was “surrounded by loopholed walls, topped by an observation tower . . . crammed with victuals and thousands of cartridges [and] equipped with two Krupp cannons, four bronze artillery pieces and a Maxim machine gun” It would prove an important jumping off point for the invasion of the Arab heartland during the war.

In 1890 the Free State authorities took another measure to improve their chances of triumph over the Arabs in the event of war by standing out “for the exact observance” of the Brussels General Declaration of 2 July 1890, which, among other things, forbade the sale of breechloading rifles and ammunition in the tropical zones of Africa. Before this time the same officials had been conspicuously liberal in their sales of firearms to the Arab zone.

Not surprisingly the official version of the outbreak of hostilities puts the blame on the Arabs, first of all for refusing to terminate slave trading within the boundaries of the Free State. They had promised to do this in the Treaty of Zanzibar, signed in February 1887 between Henry Stanley and Tippu Tip. The Free State administration appears to have begun planning for a showdown with the Arabs as early as 1889, believing that this was the only reliable way for slave trading to be ended and the authority of the Free State firmly implanted in the eastern regions.

The second element in the official version of the causes of the war was the dubious charge that Tippu Tip and his Arab cohorts were planning an alliance with their fellow Muslims, the Mahdists in the Sudan. This alleged conspiracy was used to justify the invasion of the southern Sudan by the Force Publique during the 1890s. Less partisan writers have suggested that, while the Free State was indeed eager to put an end to slave trading on its territory, this was as much because it wished to be seen to be living up to the terms of its mandate from the Berlin Conference as for any humanitarian reasons of its own. These same writers have also pointed to the emerging competition between the Free State and the Arabs over the ivory trade as a factor in bringing on hostilities.

At the outset of the fighting the Force Publique was too small to carry the battle to the enemy. The Arabs had the capacity to field 100,000 men, and only their seeming inability to co-operate among themselves stopped them from doing so. Thus, some 4,200 mercenaries had to be recruited by the Force Publique, and militia were incorporated into the regular army at an accelerated rate. These additions boosted the size of the army from 6,000 men in 1892 to 10,000 by 1894. During the course of the war, the Force Publique also absorbed some of the irregular troops of their defeated foes, principally members of the Batetela and Baluba tribes. The Free State forces had another interesting ally in their war against the Arabs – an armed force paid for by the Anti-Slavery Society and under the command of one Captain Jean Jacques. The Society’s troops operated farther east than the Force Publique, in the vicinity of Lake Tanganyika, where they began attacking Arab strongholds in 1891–2.

After desultory sparring in 1891–2, the Force Publique’s “river war” against the Arabs moved into a higher gear in the spring of 1893 with assaults against the main Arab strongholds of Nyangwe and Kasongo on the Lualaba River. Troops under the command of Commandant Dhanis used artillery to bombard Nyangwe, provoking an Arab counter attack which was repulsed with great slaughter. Nyangwe fell on 4 March and Dhanis quickly moved downstream to attack Kasongo, supported by swarms of African irregulars. Kasongo was taken “after furious fighting. In wild flight the Arabs abandoned the field and many of them were drowned in the River Musokoi”.

While Dhanis was subduing the Arabs south of the fortified base at Basoko, Force Publique troops commanded by Lieutenant L.-N. Chaltin used the fort as a base for operations against Arab forces to the north, in the vicinity of Stanley Falls. Moving swiftly by steamboat up the Congo River and into the Lomami, Chaltin’s men occupied a number of Arab villages, only to realize that the light defence of these Arab strongholds meant that Arab troops were somewhere else – delivering, as it turned out, a furious assault against the Free State’s base at Stanley Falls. Tobbak, the commandant at the Falls, “was holding out with difficulty against superior numbers, when on the 18th [of May 1893], at the moment of his greatest extremity, the [steamer] ‘Ville de Bruxelles’ drew near with the longed-for relief force under Chaltin”. Shades of the siege of Médine!

The Arab war was brought to an end by a Force Publique victory on 20 October 1893 on the Luama River just west of Lake Tanganyika. The Free State forces, under the leadership of Commandants Dhanis and Ponthier (who died of wounds after the battle), succeeded in winning “a decisive victory . . . after heavy losses on both sides”.

While it seems obvious that the major factor in the success of the Free State forces in the Arab war was the mobility conferred upon them by control of the river system, there is surprisingly little reference to this in official accounts of the war. According to the authors of the official history of the Force Publique, the Arabs were beaten because they lacked the capacity or armament to wage offensive war. They “excelled” at defensive warfare and built strong field fortifications called bomas, but, presumably, the artillery and offensive esprit of the Force Publique proved too much for them. The arms available to the Arab army varied considerably: the chiefs presumably possessed modern repeating rifles, while the common soldiers carried everything from “Long Danes” to Winchester repeaters. The situation was made worse for the Arabs, the authors contend, because of their inability to work together. The final negative factor was logistical: the difficulty of supplying such a large army in the eastern Congo, which had been “depopulated and devastated” by the slave raiders.

During and after the war, strenuous efforts were made by the Free State authorities to convince public opinion in Belgium and elsewhere that the bloody and costly conflict had been a struggle between the forces of enlightenment and progress (the Free State) and a vicious, exploitative regime (the Arabs) from which Africans were only too glad to be liberated. Until fairly recently this view won general acceptance, at least in the West. Modern scholars, however, have found reason to dissent. Using new sources (missionary records, Arab/Swahili accounts and oral histories) to supplement the sparse documentation made available in Belgian archives, historians like the missionary priest R.P.P. Ceulemans53 have constructed a somewhat different picture of the Congo Arab zone on the eve of the 1890s war. Surprisingly, some of the most telling evidence comes from accounts of participants in the conflict on the Free State side. This description of the taking of the Arab town of Kasongo, written by Captain Sidney Hinde, a British medical officer with the Force Publique during the war, is particularly illuminating.

We rushed into the town so suddenly that everything was left in its place. Our whole force found new outfits, and even the common soldiers slept on silk and satin mattresses, in carved beds with silk mosquito curtains. The room I took possession of was eighty feet long and fifteen feet wide, with a door leading into an orange garden, beyond which was a view extending over five miles. We found many European luxuries, the use of which we had almost forgotten; candles, sugar, matches, silver and glass goblets and decanters were in profusion. The granaries throughout the town were stocked with enormous quantities of rice, coffee, maize and other food; the gardens were luxurious and well-planted; and oranges, both sweet and bitter, guavas, pomegranates, pineapples, mangoes and bananas abounded at every turn. . . . I was constantly astonished by the splendid work which had been done in the neigbourhood by the Arabs. Kasongo was built in the corner of a virgin forest, and for miles around the brushwood and the great majority of trees had been cleared away. In the forest-clearing fine crops of sugar-cane, rice, maize and fruits grew. I have ridden through a single rice-field for an hour and a half.

Modern scholarship leaves the impression that by the 1880s the Arab/ Swahili raiders had put their slaving days behind them and had begun to build permanent communities in the eastern Congo with viable agricultural and commercial infrastructures and efficient systems of administration. This, it is suggested, was what made the Arabs so threatening to the expansion-minded Free State authorities, not their penchant for slave raiding or their religious fanaticism. Perhaps the best proof that there is something to this argument is the quiet homage paid to it by Free State officials themselves. Following conquest of the Arab zone, the government in Boma kept the Arab administrative system in place and even retained most of the middling Arab officials; the eastern Congo was ruled in this way until the 1920s.

LINK

http://macslittlefriends.blogspot.com/2009/10/death-in-dark-continent-first-game.html