Although the zeppelin raids proved the futility of using hydrogen-filled airships as a strategic bomber, the Germans did not give up on strategic bombing. Instead, they turned to a new weapon that came available in Spring 1917, the twin-engine Gotha G-IV bomber. The Germans hoped that this new weapon, when combined with a resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare in 1917, would drive Britain from the war. In the first Gotha raid, conducted on 25 May 1917, a fleet of 23 bombers led by Captain Ernst Brandenburg headed toward London, but because of heavy fog ended up dropping their payloads over Folkestone, killing 95 civilians and injuring 195, more casualties than any single zeppelin raid. On 13 June Brandenburg led 20 Gothas in a noontime attack on London, dropping 7 tons of bombs that destroyed the Liverpool Street Station, killed 162 people, injured 432 others, and caused more than $600,000 in property damage. Every single Gotha returned to Ghent unscathed. More significant, this one single raid inflicted more damage on London than did all the earlier airship raids combined. The British responded by withdrawing two of their top squadrons (No. 66 and No. 56) from the Western Front for the defense of London—a move that allowed the Germans to shift their attacks to British positions on the front. When the British sent the squadrons back to France, the Germans shifted back to London on 7 July, sending a formation of 22 Gothas that inflicted 252 casualties. To defend against the raids that followed, none of which comprised more than 43 Gothas, the British were forced to maintain almost 800 aircraft—approximately 50 percent were top of the line fighters—at home to reassure the public. This commitment deprived the British of much-needed aircraft for their Passchendaele Campaign and contributed at least in part to the British suffering twice as many casualties in the air as did the Germans.

These attacks both outraged Englishmen and absorbed the British High Command’s attention, leading to the appointment of Lieutenant General Jan Smuts as chair of the Committee on Air Organization and Home Defense against Air Raids. By 17 August, when the Smuts Committee issued its report, a combination of poor weather and improved British air defenses, which included the use of barrage balloons and suspended cables, was turning the tide against Germany as some missions lost as many as 50 percent of their Gothas. More important, German hopes that the civilian population would be terrorized into forcing their government to abandon the war never materialized.

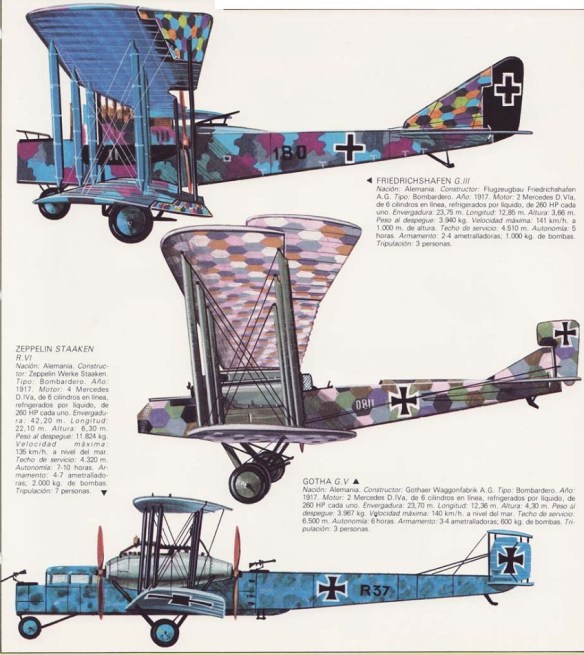

In 52 attacks on Great Britain, German Gothas and Staken R.VI bombers had dropped 73 tons of bombs, killed 857 British subjects, wounded another 2,400, and left more than $7 million in property damage. Although the bombing campaigns far exceeded any success enjoyed by the zeppelins, they did not achieve as much as they could have. Failing to recognize the extent of their success, especially in terms of forcing the British to reallocate resources, the Germans neither dedicated as many bombers nor conducted as many raids as they could have. As a result, the British gained time to improve their defenses, developing high-altitude fighters and high-altitude antiaircraft guns. More important, the bombing campaign compelled the British to merge the RFC and the RNAS together into the new Royal Air Force (RAF). By May 1918 the toll on German bombers reached the point that cross-Channel attacks were dropped altogether. If anything, the German bombing raids only strengthened British resolve, something that would be repeated in 1940.

In the meanwhile, the British, desiring to strike back at the Germans, had organized the 41st Wing in October 1917 to carry out strategic bombing raids against German industrial targets. It should be emphasized that Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig, commander-in-chief of the BEF, and Trenchard, commander of the RFC, bitterly opposed this as a misallocation of resources that should be used first and foremost to support the army’s needs on the front. Their objections had been overridden, however, because politicians—Prime Minister David Lloyd George among them—were feeling the public’s demand for revenge. Equipped with D.H.4s, F.E.2bs, and Handley-Page 0/100s, the 41st Wing began operations in the fall. It was restructured as VIII Brigade in February 1918 and as the Independent Bombing Force on 6 June 1918. By then the first Handley- Page 0/400s had begun to enter service, allowing the British to carry out highly successful raids against Rhineland cities such as Coblenz, Cologne, Karlsruhe, Mainz, and Mannheim. By the Armistice the British had carried out 675 raids against German targets, dropping more than 14,000 bombs, killing 746 Germans, injuring 1,843 others, and causing approximately $6 million in damage. Had the war continued, the massive Handley-Page V/1500 bomber would have given the British the ability to strike Berlin. Although the British bombing campaign had not really begun in earnest until the creation of the Independent Bombing Force, the British had seen enough results over such a short period of time that they would be firmly convinced of the value of strategic bombing.