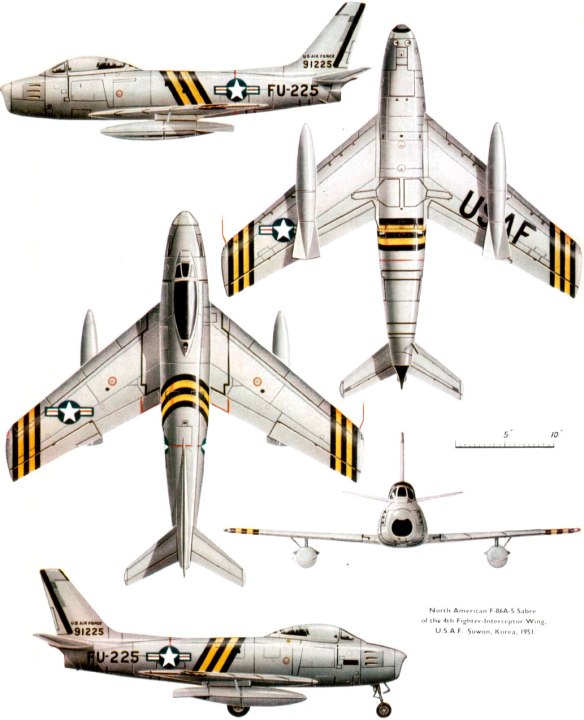

North American F-86A Sabre. North American Aviation’s second jet, begun in 1944, incorporated the German-influenced swept-wing design, to allow for higher speeds. In 1948, an F-86 exceeded the speed of sound in a shallow dive, though not in level flight. In November 1950, just a few months into the Korean War, the USAF was shocked to discover that their jets could not match the Soviet MiG-15 for speed. Sabre squadrons, not yet fully operational, were rushed to Korea. While the Sabre was slightly inferior to the MiG, the more highly skilled US pilots soon established air superiority

The development of military jets was a high-cost, high-technology business that was only going to be open to a very few players. After the Germans – clear leaders in jet-aviation technology – were put out of contention by defeat in the war, Britain found itself temporarily out in front in 1945, with its Gloster Meteor and de Havilland Vampire fighters. But the British did not have the resources to lead the way for long, and by the end of the decade they had been matched even in Europe, by the French with their Dassault Ouragan fighter and by Sweden’s Saab 29 Tunnan. Inevitably, though, it was the United States and the Soviet Union that devoted the greatest resources to military jet development and were soon reaping the rewards.

The United States was surprisingly tardy in turning to jet propulsion. The Americans in effect let the Germans and British do the ground-breaking research and then built on the results. The first US jet fighter, the Bell P-59 Airacomet, was constructed around British designer Frank Whittle’s jet engine, licensed to General Electric to build. It first flew in 1942, but performed disappointingly and was never sent into combat. The Lockheed P-80 Shooting Star, designed by Kelly Johnson’s Skunk Works in 1943, also originally had a British engine, but only came into its own when refitted with the all-American Allison J33. As the F-80, the Shooting Star was America’s first operational jet fighter – although too late for service in World War II – and gave birth to the T-33 jet trainer, in which generations of American fighter pilots were to learn the basics of their trade. The Soviet Union also used British engine technology in its jet-powered MiG-15s.

Airframe design

For crucial progress in airframe design, the Americans and Soviets learned from the Germans. The Me 262 had been designed with a partially swept-back wing. Captured documents showed that German aerodynamics experts had intended to sweep it back more fully, since their data indicated that this would reduce drag at very high speeds. They had not done so because a swept wing caused instability at low speeds, and they had no answer to this problem.

The German documents were made available to North American, which in 1945 was working on a straight-wing jet fighter designated as the XP-86. It led them to radically overhaul their design, adopting a fully swept-back wing and coping with low-speed instability by adding leading-edge slats. The result was the famous F-86 Sabre, which entered production in 1948. Its Soviet contemporary, the MiG-15, was also a swept-wing fighter – not so much a case of thinking alike as of poaching from the same source. The F-86 and MiG-15 were designed to push to the edge of supersonic flight. Whether they would be able to pass Mach 1 – the speed of sound – was, at the time of their conception, unknown.

There was widespread speculation that a “sound barrier” might block the path to any further rise in airspeed. Since no one had ever flown faster than sound, this was at least plausible. Pilots who had reached high subsonic speeds flying late- World War II piston-engined aircraft in steep dives reported violent turbulence. Another disturbing experience approaching the speed of sound was sudden loss of control of the aircraft – the controls seemed to freeze, as if all the cables to the control surfaces had been cut.