VB-2 AZON/VB-3 RAZON Guided Bombs

In 1939, even before Japan entered World War II, Japanese planners plotted a Thailand-Burma rail line to transport 3,000 tons of supplies daily in support of troops in remote Burma. Considering the formidable terrain and harsh tropical climate, the Japanese engineers projected that five years would be required to complete the 257-mile line. The biggest obstacles were the gorges and mountain cuts, which would require a multitude of bridges—some 600, total—most of them in Thailand.

Actual construction of the railroad was put off until September 16, 1942. Converging lines were begun, emanating from two existing terminals, at Thanbyuzayat, Burma, and at Nong Pladuk, Thailand (some 25 miles west of Bangkok). The lines were to be advanced toward one another. Construction crews consisted of about 61,000 Allied prisoners of war, among them 30,000 British prisoners, 18,000 Dutch, 13,000 Australian, and 700 U.S. soldiers. In addition, 250,000 Malays, Chinese, Tamils, and Burmese were used as slave labor. Of the POWs, it is estimated that 16,000 died, most of them from diseases endemic to the region and from malnutrition, abuse, and sheer exhaustion. In particular, beginning in January 1943, during an accelerated period of construction—which the labor camp authorities called the “speedo”—the prisoners were literally worked to death. Among the Asian slaves, mortality was even higher than among the POWs. It is believed that more than 80,000 died.

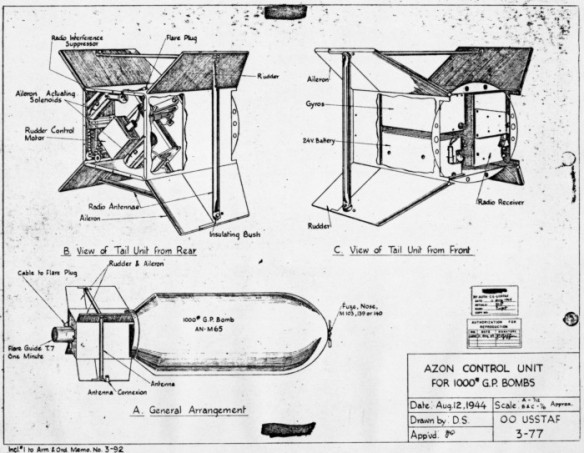

Work was completed on the railway not in five years, but in 16 months, the two lines meeting 23 miles south of Three Pagodas Pass in April 1943. The Japanese operated the line for 21 months before it was badly damaged by Allied air attacks, including those using a new type of radio-controlled “AZON” bomb. Except for 80 miles of track in Thailand between Nong Pladuk and Tha Sao, which operates today, the railroad was abandoned before the war ended.

The River Kwai Bridge is the most famous of the 600-plus bridges over which the tracks once ran. It spans 1,200 feet over the Kwai at a place the prisoners called Hellfire Pass because, at night, from the top of the mountain ridge, flickering torches along the construction site and camps looked like the fires of hell. The bridge took a full nine months to build, with prisoners and others working 18-hour shifts. Construction of the bridge was the subject of a famous 1957 film directed by David Lean and starring Alec Guinness, The Bridge over the River Kwai. Although the movie is considered a masterpiece of cinema, it has very little basis in the reality of the POW experience at Kwai or elsewhere along the Burma-Thailand Railway.

The Burma Railway, also known as the Death Railway, the Burma–Siam Railway, the Thailand–Burma Railway and similar names, was a 415-kilometre (258 mi) railway between Ban Pong, Thailand, and Thanbyuzayat, Burma, built by the Empire of Japan in 1943 to support its forces in the Burma campaign of World War II. This railway completed the railroad link between Bangkok, Thailand and Rangoon, Burma (now Yangon). The line was closed in 1947, but the section between Nong Pla Duk and Nam Tok was reopened ten years later in 1957.

Forced labour was used in its construction. More than 180,000—possibly many more—Asian civilian labourers (Romusha) and 60,000 Allied prisoners of war (POWs) worked on the railway. Of these, estimates of Romusha deaths are little more than guesses, but probably about 90,000 died. 12,621 Allied POWs died during the construction. The dead POWs included 6,904 British personnel, 2,802 Australians, 2,782 Dutch, and 133 Americans.

After the end of World War II, 111 Japanese and Koreans were tried for war crimes because of their brutalization of POWs during the construction of the railway. 32 were sentenced to death.

Further reading: Boulle, Pierre. Bridge over the River Kwai. London: Collins, 1968; Gordon, Ernest. Through the Valley of the Kwai. New York: Harper & Row, 1962; Kinvig, C. River Kwai Railway. London: Brassey’s U.K., 2003; Searle, Ronald. To the Kwai and Back: War Drawings 1939–1945. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 1986.