On 19 February 1943, Archer embarked nine Martlet Vs of 892 Squadron and on 28 February embarked nine Swordfish Mk II aircraft of 819 Squadron. She was inspected by the King the following day and then sent to shipyards on the Clyde and at Belfast for further rectification work. In early May, Archer joined the 4th Escort Group off Iceland on convoy support operations. She joined Convoy ONS 6 on 9 May and then Convoy ON 182 on 12 May, leaving these convoys on 14 May. On 21 May she joined Convoy HX 239. On 23 May, a Swordfish II of 819 Squadron sank U-752 with a Rocket Spear, a new weapon, at 51°48′N 29°32′W. The thirteen survivors were rescued by HMS Escapade. U-752 was the first German U-boat to be sunk with rockets and only the second to be sunk by aircraft that operated from an escort aircraft carrier. Archer left Convoy HX 239 on 24 May. She then joined Convoy KMS 18B on 26 June and left that convoy on 3 July. She was then withdrawn from the 4th Escort Group to take part in exercises in the Irish Sea. Following these exercises, she was sent to the Bay of Biscay on anti-submarine patrol duty, but was withdrawn from this after a week due to a lack of U-boat activity and further defects. She arrived at Devonport on 27 July and work commenced the following day. Archer then sailed to the Clyde for engine repairs, arriving on 3 August.

It was found that Archer had extensive defects and she was decommissioned with effect from 6 November 1943. She was relegated to use as a stores ship at Gare Loch. In March 1944, Archer was towed to Loch Alsh where she was used as an accommodation ship until August when she was sent to Belfast for repairs to enable her to be used as an aircraft ferry ship. Repairs were to take seven and a half months.

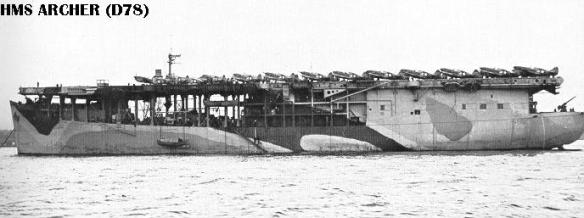

Archer was the first of thirty-eight US-built converted C3 Escort Carriers turned over to Great Britain during the period 1941–1944, and one of five motor ships (the remainder were powered by geared turbines). Unlike the others, Archer was powered by four diesel engines instead of two.

After an extensive shakedown and repair period Bogue joined the Atlantic Fleet in February 1943 as the nucleus of the pioneer American anti-submarine hunter-killer group. During March and April 1943 she made three North Atlantic crossings but sank no submarines. She departed on her fourth crossing 22 April and got her first submarine 22 May when her aircraft sank U-569 at 50°40′N 35°21′W.

During her fifth North Atlantic cruise her planes sank two German submarines: U-217 at 30°18′N 42°50′W., 5 June and U-118 at 30°49′N 33°49′W., 12 June.

On 23 July 1943, during her seventh patrol, her planes sank U-527 at 35°25′N 27°56′W. The destroyer George E. Badger, of her screen, sank U-613 during this patrol.

Bogue ’s eighth patrol was her most productive with three German submarines sunk. U-86 was sunk by her planes on 29 November 1943 at 39°33′N 19°01′W. On 30 November, TBF Avengers from Bogue damaged U-238 east of the Azores. On 13 December U-172 was sunk by her planes, along with destroyers George E. Badger, DuPont, Clemson and Osmond Ingram at 26°19′N 29°58′W. And on 20 December U-850 was sunk by planes at 32°54′N 37°01′W.

#

Defeat of the German U-boats in the North Atlantic. The climactic convoy battles of March 1943 had given a first hint that Allied antisubmarine forces were finally gaining the upper hand in the battle for the North Atlantic sea lines of communication. By early 1943, the fully mobilized American shipyards were producing vast numbers of escort vessels in addition to building more merchant ships than were being sunk by U-boats. Modern, long-range naval patrol aircraft, such as the B-24 Liberator, and escort carrier–based aircraft were closing the dreaded air gap, the wolf packs’ last refuge from Allied airpower in the North Atlantic. At the same time, Allied signals intelligence was reading the German U-boat cipher Triton almost continuously and with minimal delay.

On 26 April, the Allies suffered a rare blackout in their ability to read the German cipher, just as 53 U-boats regrouped for an assault on the convoy routes. Miraculously, two eastbound convoys, SC.128 and HX.236, escaped destruction, but ONS.5, a weather-beaten, westbound slow convoy of 30 merchant ships escorted by 7 warships stumbled into the middle of the wolf packs on 4 May. During the next 48 hours, the Uboats sank 12 ships but at an unacceptable cost: escort vessels sank 6 U-boats, and long-range air patrols claimed 3 others. Radar in aircraft and escort vessels had played a decisive role in giving the numerically overmatched escorts a tactical edge in the battle.

The commander of the German U-boat arm, Admiral Karl Dönitz, was aware of the tilting balance, but he urged his Uboat commanders not to relent. Yet many of the vessels did not even reach their areas of operations. The determined antisubmarine offensive in the Bay of Biscay by aircraft of the Royal Air Force Coastal Command destroyed 6 U-boats during May and forced 7 others to return to base.

In the second week of May, the ragged survivors of the North Atlantic wolf packs, which had operated against Convoys ONS.5 and SL.128, regrouped and deployed against HX.237 and SC.129. Only 3 merchantmen were sunk, at the expense of the same number of U-boats. In addition to radar, the small escort carrier Biter, which had provided air cover for HX.237 as well as for SC.129, was vital in denying the German submarines tactical freedom on the surface near the convoys. When the U-boats renewed their attacks against Convoy SC.130 between 15 and 20 May, escort vessels sank 2 U-boats, and shore-based aircraft claimed 3 others. SC.130 suffered no casualties. The U-boat offensive failed entirely against HX.239, a convoy with a rather generous organic air cover (aircraft attached to the convoy) provided by the escort carriers USS Bogue and HMS Archer. Not a single U-boat managed to close with the convoy, and on 23 May, a U-boat fell victim to the rockets of one of the Archer’s aircraft. The following day, Dönitz recognized the futility of the enterprise and canceled all further operations in the North Atlantic. During the month to that point, more than 33 U-boats had been sunk and almost the same number had been damaged, nearly all of them in convoy battles in the North Atlantic or during transit through the Bay of Biscay. The month went down in German naval annuals as “Black May,” with the loss of 40 U-boats. At the end of May 1943, the British Naval Staff noted with satisfaction the cessation of U-boat activity. SC.130 was the last North Atlantic convoy to be seriously menaced during the war.

References Blair, Clay. Hitler’s U-Boat War. Vol. 2, The Hunted, 1942–1945. New York: Random House, 1998. Gannon, Michael. Black May. New York: Harper Collins, 1998. Morison, Samuel Eliot. History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Vol. 10, The Atlantic Battle Won, May 1943–May 1945. Boston: Little, Brown, 1956.