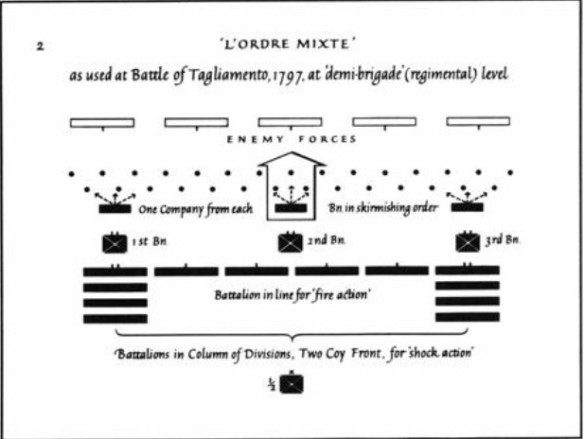

The Austrian army fought a rear guard action at the crossing of the Tagliamento but was defeated and withdrew to the northeast. The French crossed the river under artillery fire. Here Bonaparte employed his mixed order formation on a large scale that broke through the Austrian defences for 500 casualties inflicting 700.

The French army was not sufficiently strong after the fall of Mantua to push on for Vienna, possessing only 55,000 men, but in the month that followed the Directory at last recognized the truth of the military situation and made a radical change to their master plan for the conduct of the war. Hitherto the Italian front had been accorded little priority in reinforcements, but the comparison between General Bonaparte’s successes and the defeats suffered by his senior colleagues on the major German front could no longer be ignored. In consequence, the war-weary French Government reversed the priorities. Bonaparte was to be reinforced to a strength of 80,000 men by the transfer of the divisions of Bernadotte and Delmas, and henceforward his operations were to be considered the major French effort, designed to ease pressure on the Rhine and in due course to win a favorable peace with Vienna.

Typically, however, Bonaparte had no intention of delaying his offensive until the arrival of the full reinforcements. He knew that the Archduke Charles had collected at least 50,000 troops in the Frioul and the Tyrol. In late February these forces were still widely scattered, but every week that passed would afford the Imperial commander the opportunity to improve his dispositions and gather more men. A rapid blow was clearly indicated, and the French commander selected an attack toward Vienna through the Frioul. Bonaparte was by no means contemptuous of the abilities of his opponent, and his plan of campaign reflects considerable caution. No less than one third of the 60,000 available French troops were to guard the Tyrol under Joubert’s command along the River Aviso. Bonaparte calculated that if an unexpected Austrian offensive should be launched down this old route, Joubert would be able to make a fighting retreat of at least ten days’ duration to Castel Nuovo, and this would enable Bonaparte to abandon his line of advance along the Frioul and place his force on the enemy’s rear at Trent by a forced march up the Brenta valley. This, of course, was only the emergency plan. If all went well, the two prongs of the French offensive, Bonaparte and Joubert, would advance along their respective axis and eventually meet in the valley of the River Drave for the final drive on Vienna.

Preliminary operations were opened in the last week of February, when the divisions of Massena, Guieu (Augereau’s replacement), Bernadotte and Sérurier crossed over the River Brenta and drove back the weak Austrian covering forces to Primolano, which fell on March 1. This success opened up the route to Trent, and completed Bonaparte’s precautionary measures. Ahead of the Army of Italy towered the precipitous defiles of the main Alpine chain, but the main offensive had to be delayed for a week to allow the snow to clear from some of the vital passes; it was only on the 10th that the main advance was recommenced.

Bonaparte knew from intelligence sources that the Archduke Charles had concentrated his main body of troops between the towns of Spilimbergo and San Vito and calculated that the Austrian commander intended to make a fighting retreat, luring the French into the midst of the inhospitable Alps. The Imperial army could choose between four lines of retreat. The first was the valley of the Tagliamento; the second led up the river Isonzo to the great pass of Tarvis; the third stretched between Laybach and Klagenfurt and, the last along the river Mur from Marburg to Bruck through Gratz. In the weeks that followed, Bonaparte set himself to close each of these valleys in turn.

The first stage of the French march lay through Sacile to Valvasone; 32,000 men marched along the main road to Vienna, while Massena with 11,000 more remained in the foothills of the Alps to guard the left flank and prevent any attempt by Charles to make a dash for the Tyrol. On the 14th, Massena defeated a small force led by Lusignan near Serraville, and the following day found the advance guard of the main body in Sacile after a sharp skirmish. The first large barrier, the river Tagliamento, had almost been reached. On March 16, Guieu and Bernadotte stormed over the river under cover of a heavy artillery bombardment, taking the Austrians by surprise and capturing 6 guns and 500 men. The Imperial army fell back on Udine, and Bonaparte had successfully penetrated the first enemy line.

The French gave the Archduke no rest, but pursued him to the line of the Isonzo while Massena advanced on Tarvis. Charles despatched three divisions to assist Lusignan hold the gorge dominating the town, but they arrived too late, and shortly found themselves caught between two fires as Bonaparte moved against their rear. Many of the rank and file eluded capture by fleeing into the mountains, but 32 cannon, 400 wagons and 5,000 prisoners fell into French hands. Meanwhile, Bernadotte was in pursuit of the section of the Imperial army retiring on Laybach, and General Dugua seized the great arsenal of Trieste with a small force of cavalry. Thus the Austrians were forced to abandon their second set of communications, but Bonaparte was already growing anxious about the length of his own communications. To render these safe, he established a new center of operations, intended to serve as a base for his next moves, at Palma Nova.

During this period Joubert was achieving considerable successes in the Tyrol, advancing as far as Botzen, and Bonaparte knew that it was time to launch his third attack. The target was now Klagenfurt, and to secure his main body’s left flank from the possibility of attack by an Austrian force moving from Innsbruck down the Brenner Pass, Bonaparte ordered Joubert to occupy Brixen athwart the main road. On March 29, the main army entered Klagenfurt with three divisions, those of Massena, Guieu and Chabot (who had taken over Sérurier’s command owing to his renewed sickness), and Bonaparte was in a position to open communications with Joubert down the Drave and Puster valleys. But at Klagenfurt the French impetus was exhausted. With large detachments at Brixen and on the Isonzo guarding each flank, and Victor with a further force far away in the Romagna, Bonaparte no longer had sufficient forces to continue the drive on Vienna. To free some of his outlying forces to join up again with the main body, the young general took the bold decision of abandoning all his communications and set up a new center of operations at Klagenfurt. Joubert, Bernadotte and Victor all received orders to concentrate on the new center, only 1,500 men under Friant being left to guard Trieste.

However, now a further difficulty arose. The success of the drive on Vienna depended on a concentric advance from Italy and the Rhine by Bonaparte and Moreau acting in concert, but the latter showed no sign of taking the offensive. This left Bonaparte in an unenviable quandary. He was not strong enough to advance on Vienna alone, but if he halted at Klagenfurt, or withdrew, the campaign was lost. As day followed day without any further move by the Army of Italy, Austrian morale steadily rose.

Where arms alone could not achieve his purpose, Bonaparte turned to diplomacy. On March 31 he addressed an appeal to the Archduke Charles calling for a suspension of hostilities, hoping thereby to win a short delay which would give Moreau time to take the offensive. To give the impression that he was speaking from strength, the Army of Italy daringly pushed ahead and on April 7 occupied Leoben. The advance guard reached the Semmering Pass, catching a glimpse of the spires and towers of Vienna 75 miles away to the north. The same day, the Austrians agreed to a five-day suspension of hostilities.

This, however, did not solve the problem more than temporarily; indeed the situation soon became steadily worse. Moreau still delayed his offensive, while the Tyroleans and the Venetians took the opportunity offered by the progressive withdrawals of Joubert and Bernadotte to stage risings. Bonaparte again had recourse to diplomacy. On the 13th, he secured a further extension of the armistice for five more days, and on his own authority, without waiting for the arrival of General Clarke, the Directory’s official plenipotentiary, he proposed on the 16th the basis for a full set of formal negotiations. As the Imperial court hesitated, the tension rose. If April 18 arrived without news of a French move on the Rhine or a favorable response from the Schönbrunn, Bonaparte’s weakness would be revealed and the gamble lost. On the very last day, the Austrians gave way. Aware that Hoche and Moreau were on the point of crossing the Rhine, the Imperial ministers advised the Emperor to sign the Preliminaries of Leoben. Certain of the terms were subsequently modified in the Peace of Campo Formio signed on October 17, 1797, but Bonaparte’s original suggestions were largely adopted. In due course the Emperor agreed to cede Belgium to France, admit her occupation of the left bank of the Rhine and the Ionian islands, and recognize the new Cisalpine Republic formed by uniting Milan, Bologna and Modena. In return, the French undertook to hand over the Republic of Venice, Istria, Dalmatia and the Frioul to Austria, thus leaving the Schönbrunn a foothold in Italy—practically a guarantee of future war.

The agreement of Leoben formed a fitting climax and termination to the hard-fought and extended Italian Campaign of 1796-97. With a few pauses, operations had continued for more than twelve months, and the strain on all concerned is shown by the high rate of disabling illness which afflicted the French senior officers as well as the rank and file. The fighting had nearly always been severe, for the regular Austrian army was a doughty opponent for all its outdated doctrines, and the greater number of its generals were far from being nonentities. The French citizen-soldiery might laugh at the “walking muskets” of the Imperial armies, but it took every particle of their famed élan and intelligence to overcome their opponents, and all the budding genius of Napoleon Bonaparte to out-think and out-maneuver their generals.