Battle of Fornovo

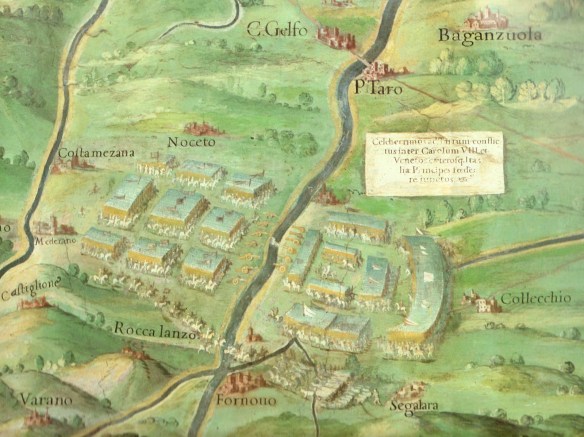

In the period 1490-1560, France was actively at war for around 42 years. 13 Such a military effort needs explanation, which is partly the theme of this book. As an introduction to this analysis, though, a degree of narrative is necessary in order for the problems to be placed in context. On 2 September 1494, Charles VIII crossed the pass of Mont-Genevre and began his descent into Italy for a long-planned challenge to the Aragonese dynasty in Naples. The fact that he faced a march right through the peninsula is indication enough that his plans involved alliances with some of the powers of Italy. This was not just an `invasion of Italy’, yet it was seen there at the time to signal a great upheaval and a new age. The march of the intimidating French army was rapid. Charles had reached Asti by 9 September, on 17 November he was at Florence and then, by 31 December, Rome. French troops in the Romagna committed atrocities in capturing cities allied with their enemies. Piero de Medici of Florence hastened to submit, while Pisa took the opportunity to revolt from Florence. The political balance of Italy was destabilised and Medici power disintegrated. The rapid collapse of the position of King Alfonso II and then of Ferrante II of Naples, while the French advanced to lay siege to their fortresses, allowed Charles VIII to enter Naples as King on 22 February 1495. The response was the formation in March 1495 of a remarkable alliance between powers that had hitherto been enemies – Venice, Milan, the Pope and Ferdinand of Aragon – which forced the French to return from Naples before they were cut off, leaving a garrison behind them (20 May). Rapid marches through Tuscany and then across the Appenines, saw the French confronted at the start of July by the army of the League, commanded by the Marquess of Mantua. The stage was set for the battle of Fornovo (6 July), long regarded as a turning-point in European history. In fact, the battle was inconclusive. The destruction was great on both sides and Italian casualties greater but the only (though crucial) advantage to the French was to gain a respite that enabled them to regain friendly territory at Asti on 15 July. This first campaign of the Italian wars is emblematic of what was to follow, for France effectively gained little. Ferrante II regained Naples and the isolation of the French garrison under Orléans (the future Louis XII) at Novara forced the conclusion of the peace of Vercelli with Ludovico Sforza, the ruler of Milan (9 October). A sort of guerilla war lingered on in Naples between Ferrante II (now supported by the Venetians and Spanish) and the French garrisons commanded by Montpensier and Stuart d’Aubigny, who were left without money to pay their men. This culminated in the defeat of the French by the great Spanish commander Gonzalo de Cordoba at Atella (July 1496) and the evacuation of the last French footholds in Calabria, though Ferrante II died soon after his victory. According to Commynes, Charles always had in mind to return to Italy, but died before he could so (7 April 1498).

Louis XII came to the throne with claims to both Naples and Milan. First, though, he needed Pope Alexander VI’s support for the annulment of his marriage. This done, he began preparations for a new invasion of Italy. Ludovico il Moro had made enemies of the Venetians and Emperor Maximilian and his position crumbled as the French army entered Lombardy. Hearing of Ludovico’s flight and the capture of Milan, Louis hastened to enter the city as duke (16 October 1499) and also brought Genoa into his obedience. The game, though, had only just begun. Ludovico used his financial resources to buy Swiss support, recaptured Milan in February 1500 and then Novara. French garrisons had been diluted for a side-show in occupying places in Emilia held by Caterina Sforza. A new French military effort commanded by La Trémoille pursued Sforza to Novara in April, where he was captured trying to escape after his Swiss refused to fight. French power was further deployed by the sending of an army into Tuscany under Beaumont to subdue Pisa to Florentine power, though the operation was a humiliating failure that contributed to poor relations with the new Florentine Republic (July 1500).

Machiavelli thought that Louis made two major mistakes: first, his links with the Pope led him to support Cesare Borgia in his acquisition of the Romagna and thus bolster papal power; secondly, his confrontation with the Aragonese dynasty in Naples, now ruled by King Federico, brought Spanish power into Italy. First, though, he concluded a secret deal with Ferdinand (Grenada, late 1500). France was to get Naples itself and the Abruzzi; Aragon, Puglia and Calabria. The French army again marched via Rome, this time under the command of Stuart d’Aubigny (May 1501), while Cordoba advanced in the south. Federico fell back on his fortresses. Capua, though, was taken by assault and Federico threw himself onto the mercy of Louis (receiving the duchy of Anjou in compensation). War was not long in breaking out between the erstwhile allies over the division of the spoils. The first disaster was the defeat of Nemours’ army at Cerignola (April 1503) by Cordoba’s tactic of digging into a fortified position and forcing his enemy to break on his trenches. In August, Louis despatched two armies to confront Spain, one to Naples and another (abortive) into Roussillon. On 29 December 1503, after a long period of skirmishing around the river Garigliano, Cordoba definitively crushed the French army that had been reinforced by the Marquesses of Mantua and Saluzzo. The survivors fled to Gaeta, which shortly afterward surrendered (1 Jan. 1504). Naples was now in Spanish power. The French now dominated Milan, the Pope central Italy and Spain the south.

A sort of condominium now existed, symbolised by the meeting of Louis XII and Ferdinand at Savona in June 1507 and the Spanish King’s marriage to Germaine de Foix. Louis in person led the army necessary to put down the rebellion of the Genoese that had been encouraged by the Emperor Maximilian and began a campaign in January 1507 that culminated in his entry by agreement into Genoa in April, after a ferocious and hard-fought series of encounters. The whole balance of power was now overthrown by the ambition of Pope Julius II to regain control of the Romagna, partly occupied by Venice after the death of Cesare Borgia. Under cover of a universal peace for the defence of Christendom, in December 1508 he finally arranged the alliance with France and the Emperor known as the League of Cambrai, aiming at a common attack on Venice and division of the spoils. Venice refused to give way and Louis XII in person led his army across the Adda on 9 May 1509 into Venetian territory. On 14th the Venetian army under Alviano (which had not concentrated all its forces) was heavily defeated at Agnadello. Venice survived by popular resistance against French and Habsburg occupation and by yet another reversal of alliances by Julius II, who lifted his excommunication in February 1510. The Republic regained control of much of its Terraferma, though henceforth played a much more careful role in international politics. The war now developed into a contest between France and the Pope for control of the Romagna. This shift culminated in another `Holy League’ (5 October 1511), which brought together the Pope, Venice, Henry VIII and Ferdinand against France. France was now beleaguered on several fronts in a way that was to recur through the first half of the 16th century. Measures had to be taken for defence against the English in the north and an English force under Dorset landed near St. Jean de Luz in Gascony (though let down by its ally, Ferdinand, who failed to provide any cavalry). In Italy, the League moved in January 1512. French forces, led by a capable general, Gaston de Foix, faced down its army, recaptured and sacked Brescia. Gaston now decided to force the League to a decisive battle by besieging Ravenna. On 11 April 1512, the League’s 20,000 men faced 25,000 French in one of the bloodiest battles of the period, which involved a furious artillery bombardment by the French. The League army broke but Gaston was killed and casualties were heavy on both sides. Despite their victory, the French were on the verge of collapse. Their best general lost, they abandoned their march on Rome and, with Swiss forces entering Lombardy against them, they were forced to evacuate the strongholds of Milan one by one (May 1512). Peace with Venice (14 March 1513) seemed to provide the opportunity for a French return. A new army led by La Trémoille crossed the Alps in May 1513 to join with the Venetian army against Massimiliano Sforza and his Swiss allies, now besieged in Novara. However, the French went down to a defeat by the numerically inferior Swiss sallying out from the city (6 June 1513). In the north, Henry VIII invaded in person and (with halfhearted help from Maximilian) captured Thérouanne and Tournai and defeated a French army of relief at the battle of the Spurs (16 August). In the east, Swiss forces entered Burgundy and in September forced the garrison of Dijon to surrender, extracting a ransom of 400,000 ducats and agreement by France to give up Milan. Far to the south, Ferdinand had profited from the fighting to invade and occupy permanently the kingdom of Navarre, hitherto ruled by the French Foix-Albret dynasty. Louis XII had thus lost practically all the gains of his reign and more. In Italy, the defeat of France satisfied most of the leading powers. But, after concluding peace with England, Louis was on the verge of yet another campaign in Milan when he died (1 January 1515).