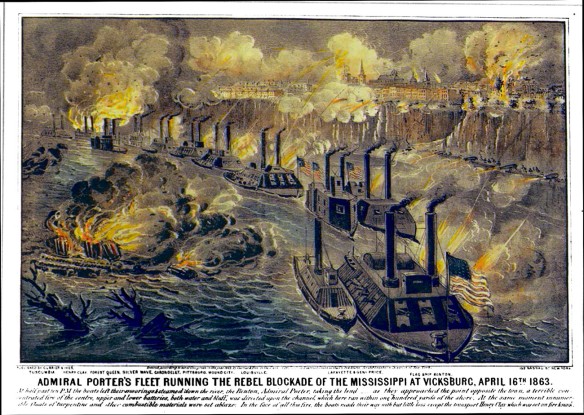

He was blessed with luck: on the night of April 29, with his troops encamped below Vicksburg at Grand Gulf, a local black man came in with the news that a crossing might be made a little lower down at Bruinsburg, near Grand Gulf. The information proved accurate. In a five-hour engagement, on the night of April 16-17, Flag Officer David Porter had already run the batteries of Vicksburg to a point thirty miles below the city, his gunboats protected by bales of cotton piled on their decks and manned by watermen who volunteered from the ranks of the army. One gunboat was sunk but three got through, and by April 22 sixteen transports and barges were sailed down. On April 30 the fleet began to transport the army across the river at Bruinsburg. To distract Pemberton, the Confederate defender of Vicksburg, Grant simultaneously despatched Colonel Benjamin Grierson on a long-distance cavalry raid with 1,700 horse soldiers. Starting from La Grange, Tennessee, near Memphis, on April 17, he had ridden south between the Mobile and Ohio and Mississippi Central railroads destroying track and burning rolling stock. He also severely damaged the Southern Railroad before he joined forces with Banks at Baton Rouge on May 2. Grierson, by profession a music teacher, proved to have exceptional talent as a mounted marauder. In a sixteen-day march of 600 miles he devastated central Mississippi, tearing up fifty miles of railroad track and living off the country.

Pemberton had now taken his army out of Vicksburg to challenge Grant in the open field, much to the anxiety of Jefferson Davis and General Johnston. They ordered him back into Vicksburg, warning that he would lose both his army and Vicksburg if he fought beyond the protection of its defences. Pemberton disagreed. He had 30,000 troops to Grant’s 10,000 and was confident he could hold his own and perhaps drive Grant back into Tennessee. He therefore arrived in central Mississippi, manoeuvring between the river and the city of Jackson, the state capital. Grant was unperturbed. As he wrote in his memoirs, “I was now in the enemy’s country, with a vast river and the stronghold of Vicksburg between me and my base of supplies. But I was on dry ground on the same side of the river with the enemy. All the campaigns, labors, hardships and exposures from the month of December previous to this time that had been made and endured, were for the accomplishment of this one object.”

Grant’s reference to his “base of supplies” is highly significant. He opened his own account of Vicksburg with the observation: “It is generally regarded as an axiom in war that all great armies moving in an enemy’s country should start from a base of supplies, which should be fortified and guarded.” Now Grant was caught up in a vast, wide-ranging campaign in the interior of the Confederacy whose nature had forced him to diverge from geometry. Today technical experts would say that he was “operating on exterior lines,” circling around the Confederacy’s heartland, seeking where he might penetrate. A less imaginative man than Grant would probably have sought to define a geometrical base and line of operations. What Grant did, after bypassing Vicksburg, defied all contemporary rules of strategy. After effecting the rendezvous between Porter’s fleet and his Army of the Tennessee, he had used the gunboats and transports to ferry his army across the river to the east bank.

From Grand Gulf he had sent two of his corps, those of McPherson and the tiresome McClernand, to march inland eastward towards Jackson, where Joseph E. Johnston was struggling to organise a new army. Johnston had been put in overall command of Confederate Mississippi on May 9. He fielded about 20,000 troops to the Union’s 29,000 and might have made a fair fight of it, had Grant advanced and deployed in an orthodox fashion. Grant did not. Having abandoned the rules of Jominian warfare, he now also abandoned the rules of organised campaigning. Instead of bringing supplies with him, or organising a line of supply from the rear, he decided not to bother with supplies but to live off the land, as Sherman had done in the Arkansas campaign of 1862. He thus surprised Johnston at Raymond, outside Jackson, on May 12. Two days later the victorious Union troops defeated Johnston at Jackson, driving Pemberton to take his small army to a place on the railroad to the east of Jackson called Champion’s Hill, so named after a local plantation-owning family whose son was an officer in the 15th Mississippi. The town was highly defensible, standing as it did on a ridge seventy feet above the surrounding plain. On May 16, the Champion’s Hill position was attacked with success by the Union. McPherson’s corps caused the Confederate line to cave in. McClernand’s corps attacked less aggressively. This increased Grant’s lack of trust in him, which was to result in his dismissal on June 19.

From Champion’s Hill, Grant pressed on to the Big Black River, which ran between him and Vicksburg. The rebel position was attacked on May 17 and at once gave way, after which Pemberton’s ragged and half-starved army fell back within the lines of Vicksburg. Grant at once took the city under siege, and during May 19-22 he launched a series of assaults on the defences, all of which cost the Union heavily, so heavily that a soldier of the 93rd Regiment described the attack as like “marching men to their deaths in line of battle.” After the last and most deter mined assault of May 23, Grant reverted to the tactics of deliberate siege. During that night, Union soldiers, whose attacks had carried them to the very lip of the Confederate entrenchments, stealthily withdrew to safer positions. The besiegers had suffered over 3,000 casualties during the great assault of May 22, at least 1,000 of which were caused by McClernand grotesquely demanding reinforcements for a success he had not achieved.

Johnston did not appear nor would he throughout the weeks of siege that followed, though the Vicksburg newspaper, in an effort to sustain morale, constantly reported his approach. The newspaper was now printed on the back of squares of wallpaper. Newsprint was not the only commodity in short supply; so were bread, flour, meat, and vegetables. The garrison and the citizens, who had dug themselves shelters against shellfire in the sides of the city’s sunken roads, subsisted on mule meat, and peanuts, “goober peas,” supplemented by skinned rats. Grant essayed his first assault on May 19, which was repulsed with heavy loss but renewed on May 22, again without success, despite a supporting bombardment by 300 guns firing from positions on land and on gunboats. On May 25, Pemberton, from within the fortress, declared a truce to enable the burial of the dead and the collection of the wounded. The stench of decomposing bodies hung around the defences. The same day, however, Grant ordered the renewal of deliberate siege, to be mounted against the sector dominated by the 3rd Louisiana Redoubt, or Fort Hill, as the Union soldiers called it. There were several more assaults in the ensuing weeks; in the intervals, Johnny Reb and Billy Yank fraternised across the earthworks, gossiping, exchanging taunts, threats, and boasts but also necessities including Union coffee and Confederate tobacco, as long as such supplies lasted.

Confederate defences at Vicksburg were so strong that, as would happen at Petersburg in 1864, the Union set about undermining them in an effort to secure a breach. Once a breach was established across the river on dry land, a crossing to the outworks of Vicksburg was effected with surprising ease. The difficulty in investing the fortification remained. It was carried out by classic European siege technique, sapping a way forward by digging entrenchments and parallels, but with an American variant. Ahead of the sap diggers, the sappers, the besiegers pushed a shot-proof shield, the sap-roller, which protected the sappers as they entrenched their earthworks. At intervals the sappers dug a battery position, in which artillery was installed to keep the Confederates under fire at decreasing range. By June 7 the most advanced battery was 75 yards from the parapet of Fort Hill. The besiegers kept up a relentless rifle fire. The sappers also refined their task of sap-rolling by bringing up a railroad car loaded with cotton bales to absorb the enemy’s fire, but the rebels reversed the advantage so gained by firing incendiary bullets into the railroad car, setting it alight and burning it to the ground. Nevertheless, the saps were pressed forward and by June 22 the sappers were at the foot of the Fort Hill breastwork. Colonel Andrew Hickenlooper, commanding the approach, then conceived a new technique. Calling for volunteers with experience of coal mining, he paid them to drive a shaft under the Confederate position. By June 25, it was completed, 45 yards long and ending in a chamber packed with 2,200 pounds of gunpowder. At 3:30 p.m. on June 25 the vast charge was exploded and most of Fort Hill rose into the sky as dust and ashes. When the cloud cleared, the attackers saw to their dismay that the defenders, anticipating the explosion, against which they had counter-mined, had dug a new parapet across the interior of the fort, from which they could shoot down at the Union soldiers as they stormed into the crater. Grant pressed attacks all evening and night until the floor of the crater was slippery with blood, but still the defences held. Eventually, after the loss of 34 men killed and 209 wounded, the assault was called off.

Almost immediately, however, the Union resumed tunnelling and by July 1 had driven a new shaft under the left wing of the fort, which was packed with powder. The Confederates counter-mined, using six slaves to do the digging. On July 1, 1,800 pounds of gunpowder was detonated by the Union miners, which destroyed the Confederate counter-mines and killed the counter-miners, all save one slave who was blown clean through the air, to land in Union lines. No assault, however, followed the explosion, which largely destroyed the 3rd Louisiana Redoubt. Instead, the attackers came up rapidly and opened a drenching fire on the entrance to the redoubt, which the Confederates tried to close with a new breastwork, eventually with success. Siege warfare was resumed all along the Vicksburg perimeter, where in some places the two sides were separated only by the thickness of a single parapet. New mines were begun in several places and trenches widened to prepare for a further ground assault, which Grant proposed to make on July 6. Unknown to the Union, though it was with reason suspected, the defenders were at their last gasp. At Milliken’s Bend, 15 miles northwest of Vicksburg, on June 7, two regiments of black troops, eligible to bear arms since the Emancipation Proclamation, bravely repelled a Confederate attack, though at heavy cost to themselves.

Pemberton, meanwhile, was having boats built from the timbers of dismantled houses and so planning to force an escape to the eastern shore. Many of the garrison were on the point of mutiny, since they were starving. It was obvious that Pemberton would be forced to surrender very shortly. Word of the garrison’s demoralisation had reached Grant, and he was reluctant to mount further costly attacks. Johnston was approaching from the east, but, outnumbered as he was, it was most improbable that he could raise the siege. On July 1, Pemberton questioned his subordinate commanders to test their opinion as to the likely success of an effort to break out. Two replied advocating surrender, the other two in almost the same terms. The condition of the garrison was desperate. The soldiers, together with the 3,000 remaining civilian residents, were starving, the men in too weakened a condition to maintain a steadfast defence. In the days after July 1 the spirit of the garrison collapsed. On July 3 white flags appeared at several places on the parapets, and at the 3rd Louisiana Redoubt voices were heard calling for a cease-fire. A Union party went forward to investigate and returned with two Confederate officers, blindfolded as the protocol of siege warfare required. One of them was Pemberton’s aide-de-camp, carrying a letter for Grant. Pemberton had written to spare any further “effusion of blood,” the words Lee was to use at the surrender at Appomattox two years hence. He was also requesting the appointment of commissioners to arrange terms of surrender, a normal and conventional procedure at the termination of a siege. Grant’s view of terms was established and well-known. It was the same as he had offered at Fort Donelson in February 1862: “No terms except unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted.”

Grant, who had served with Pemberton in Mexico, was on this occasion less peremptory, though he made his meaning equally clear. Pemberton attempted to prolong discussions by meeting Grant outside the line, but the Union commander would not yield an inch. Pemberton quibbled and it seemed that the fighting might resume, until Pemberton’s subordinate suggested that some chosen junior officers should discuss the matter. Grant agreed, on condition that he was not bound by what they might agree to. His emissary, General Bowen, returned to Grant with Pemberton’s suggestion that the garrison be accorded the “honours of war,” which meant that it should be allowed to march out but under arms, subsequently to be retained. Grant refused the suggestion outright but said that he would make a final offer before midnight. He held strictly to his view that the enemy were in rebellion and could not enjoy any of the privileges of legitimate combatants. In the interval he held a council of war, though much against his better judgement, at which General James McPherson, whom Grant held in high esteem, suggested that Grant offer to parole Pemberton’s troops. Since even if Pemberton submitted to an unconditional surrender, Grant would face the burden of shipping Pemberton’s thousands into captivity, Grant agreed and the proposition was sent into the fortress. Pemberton, whose starving soldiers were on the point of mutiny, accepted and on July 4 the garrison marched out to be paroled. Pemberton’s officers were allowed to retain their swords and one horse cart. The other weapons and regimental colours were to be stacked outside the lines. Paroles were written and signed for the prisoners, 31,600 in number. Grant permitted them to return inside Vicksburg and then allowed them to drift away. As he was sure that, if left at liberty, they would return to their homes and not resume military service, he felt that this was a safe course of action. So, generally, it proved to be. The defeated Confederates were indeed content to find their own way from the battleground, a disturbing outcome of the Mississippi Valley campaign, with implications for the whole of the South. The occupation of the city that followed was notably good-natured, with Union troops distributing their rations to the emaciated survivors. The value of their victory perhaps disposed the victors to be generous. As Grant correctly observed, “The fall of the Confederacy was settled when Vicksburg fell.”

News of the surrender of Vicksburg caused General Frank Gardner, who commanded the garrison at Port Hudson, last of the Confederate blocking places on the Mississippi, to surrender on July 8. Port Hudson, very strongly fortified, controlled a bend in the river with twenty-one heavy guns. At surrender, the garrison numbered 6,340, but the soldiers were weakened by shortage of food. They had also been subjected to assault from land and water for many previous weeks. Surrender was a relief. As at Vicksburg, the incoming Union soldiers offered their rations to the starving defenders.

Not only did this place the line of the Mississippi under Union control, so that, in Lincoln’s words, “the Father of Waters again goes unvexed to the sea,” it also cut the Confederacy in half, slicing off the western half, including the whole of Texas and the territories of Nebraska, New Mexico, Nevada, Utah, Colorado, and what would be Oklahoma from material and most other assistance from the Old South. Huge stocks of cattle, horses, and mules were lost to the Confederacy by the capture of Vicksburg and Kirby Smith, commander of the Western Department, was told by Jefferson Davis in the aftermath that thenceforth he would have to manage by himself.