The news of defeat at Gettysburg was succeeded the following day, July 4, 1863, by news of the surrender of Vicksburg, which had been a key to the Confederacy’s ability to close traffic along the Mississippi River between the Midwest and the exit to the high seas below New Orleans. The opening was more symbolic than substantial since the movement of goods in bulk from the interior to the ocean by rail had already overtaken the traditional river traffic. Nevertheless, securing the line of the Mississippi had been at the heart of Winfield Scott’s Anaconda Plan and was central as an aim both to Union strategy and to Union hopes for the prosecution of the war.

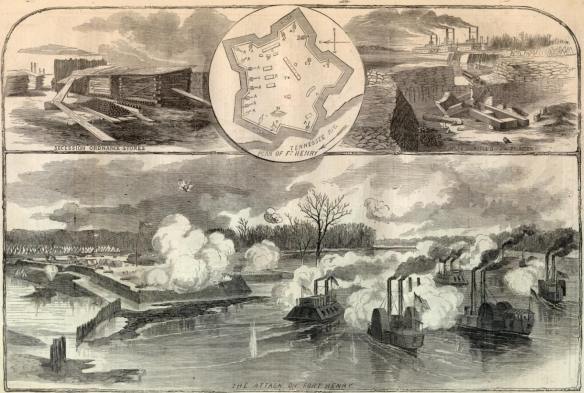

The victory also simplified the way forward in the West, for which no coherent Union strategy had been laid down. Indeed, the war in the West (which is known today as the south-central United States) had not followed any organised scheme but had developed as a result of opportunities presented by sequential successes. The first of these, from which all the rest followed, was the capture of Forts Henry and Donelson, both in Tennessee, in February 1862. Grant had decided to attack these two places because they stood on the Confederate frontier in the West but also because they controlled movement along the Cumberland and Tennessee rivers and led into territories Lincoln eagerly sought to occupy, particularly loyal eastern Tennessee. Militarily, rivers in the West played a quite different role from those in the East. The eastern rivers in Virginia, particularly, were chiefly valuable as water obstacles, most useful to a defender. In the West, the rivers were avenues of movement—the Mississippi foremost, but the Ohio, Tennessee, and Cumberland also, since they offered points of penetration to the Union into Confederate territory, for the mass movement of troops, artillery, and supplies. The Mississippi-Ohio-Tennessee-Cumberland complex was of particular strategic importance since, in a Jeffersonian phrase, they interlocked, their interconnecting points or confluences, if held, conferring great advantages to the occupier. How keenly Grant perceived the importance of the riverlands is difficult to judge. Grant was as hindered by lack of good maps as any other general campaigning at the time inside the South, but it may be supposed that he glimpsed opportunities. Moreover, as soon as Henry and Donelson were taken he was off down the Tennessee, to strike deep into Confederate territory and to fight the bloody battle of Shiloh on the riverbank at Pittsburg Landing. Victory there allowed the Union’s superior commander in the West, Henry Halleck, to open an advance on the railroad centre of Corinth, which the newly arrived General Beauregard evacuated before it could be captured. A newly formed army under General John Pope had already captured the fortified positions at New Madrid and Island No. 10 for the Union. The battle at Shiloh on the Tennessee River had thus indirectly opened the lower Mississippi to a Union advance. After the fall of Island No. 10, only Fort Pillow and Memphis stood between the Union force in Tennessee and Vicksburg on the lower reaches. Memphis fell quickly after the evacuation of Corinth, thanks to the intervention of a fleet of naval ironclad rams, constructed by a Pennsylvania designer, Charles Ellet. In a hard-fought battle on June 6, Ellet, several of whose close relatives served aboard his ships, engaged the Confederate flotilla at Memphis and defeated it, by gunfire and ramming. The attack was quite unexpected and shocked both the Union and the Confederacy by its surprise and swift conclusion. Before the end of the day, the Union flag flew over the Memphis post office. In a little over four months, vital stretches of the South’s largest waterways had fallen under Union control; all of them were under threat.

This dire situation had been brought about by the nature of Confederate strategy, such as it was, in the western theatre. The reconsideration of Confederate strategy in the West was the work of George Randolph, the Confederate secretary of war. He believed in the coordination of operations by all the armies deployed from the Appalachians to Arkansas, of which there were several. He began by ordering General Theophilus Hunter Holmes of the Trans-Mississippi Department to bring his army across the river to assist in the defence of Vicksburg. When informed, Jefferson Davis at once vetoed the order. He emphasised that commanders of departments were expected to stay within their own departments and that any movement of troops must be authorised by the president. Randolph correctly recognised that this statement of policy deprived the secretary of war of any function and promptly resigned. Davis replaced him with James Seddon, a semi-invalid but an experienced Virginia politician. Seddon was less likely to take offence than Randolph; he also had the gift of planting ideas in Davis’s mind in such a way that the president thought they were his own. Seddon’s principal idea on taking office was that the Confederacy must rescue its western provinces from capture by the Union and that required the reconstitution, under a single commander, of a Department of the West. Davis was persuaded not only that he had thought of the plan for himself but also that he had chosen the commander, Joseph E. Johnston. That was a remarkable achievement since Davis and Johnston had a long history of quarrelling. Johnston was, however, a general of undeniable talent, if of quite different views from any other Confederate leader.

At an early stage, Albert Sidney Johnston and Jefferson Davis had together decided on a cordon defence of the lower Confederacy, along a line close to the western flanks of the Appalachians and reaching out via Bowling Green, Kentucky, and Forts Henry and Donelson, Tennessee, to Columbus on the Mississippi, a distance of 300 miles. Because the bulk of Confederate troops, and the best troops at that, had to be kept in Virginia on the Richmond-Washington axis, there were insufficient forces left to guard the long western frontier, and they were not of the first quality, either in leadership, equipment, or human fighting power. Nor did they benefit from the configurations of geography, since there was little high ground on which to form defensive lines, while the waterways flowed in precisely the wrong direction, as was not the case in Virginia. The South had to resort to the expedient of holding key points, on railways or rivers, as a principal means of impeding Union advances. It was in that context that the giving up of important places such as Island No. 10 cost them so dear. Even worse, because it inaugurated the fallback, was the surrender of the so-called Gibraltar of the Mississippi Valley, Columbus, Kentucky, in February 1862. By summer 1863 the whole run of the Mississippi, southward from Columbus, with the exception of Vicksburg and Port Hudson, was under Union control. The most spectacular Union success on the river had been the capture of New Orleans, the largest city of the Confederacy, in April 1862. The capture of New Orleans was the first noted achievement of the United States Navy in the war so far. The victor was Flag Officer (Admiral) David Glasgow Farragut, a Southern-born regular naval officer who had served the Union for thirty years and was unflinchingly loyal to it. When at secession time he heard other Southern-born naval officers discussing the military situation, and whether to go with their states, he warned that they would “catch the devil before they were through with this business.” He had fought in the War of 1812 but retained a keen and original mind and the courage of a fire-eating midshipman.

Farragut opened the campaign on the Mississippi in February 1862 when he led a fleet of eight steam sloops and fourteen gunboats over the shallows of the river’s mouth and 15,000 soldiers under General Benjamin Butler. The first obstacles to further advance were the two Third System forts, St. Philip and Jackson, which had fallen into Confederate hands at secession. Farragut bombarded both heavily for six days; when both declined to surrender, he decided to force his way through the chain barrier they defended, which, by April 25, he had done with his fleet, largely intact. He then proceeded immediately to New Orleans, exchanging fire with the riverside defenders as he went. When he got to the city, he met Butler’s troops who were on hand. By April 27, New Orleans was in Union hands; its capture, the largest city in the South, was a tremendous fillip to the North’s prestige and consonantly depressing to the Confederacy. Butler proved a harsh occupier, running a stringent military administration, though the city had never been a stronghold of secession. By June the Farragut fleet had got as far upstream as Vicksburg, taking en route Baton Rouge, the Louisiana state capital, and Natchez, and had made contact with the upstream Federal river navy. Both, however, had been fired on so heavily by the guns of Vicksburg and those on the adjoining riverbanks that they had not been able to linger in the city’s vicinity nor to make any impression on its fortifications or garrison, which had been reinforced by the arrival of troops under Van Dorn. It had become clear that Vicksburg could only be taken, and so the river opened, by the effort of a large army operating on the eastern bank of the Mississippi. How to position such an army was to tantalise the thoughts of Union commanders for the ensuing year.

Quarrels over authority compounded the difficulties of the Union army on the Mississippi at the outset. Because of his successes at Henry and Donelson and at Shiloh, Grant was appointed commander of the Army of the Tennessee on October 25, 1862. Unfortunately a potential rival, John McClernand, who engaged considerable support in Washington, embarked on a personal scheme to capture Vicksburg at precisely the moment that Grant began on his own campaign. McClernand, a former congressman, was a protégé of Stephen Douglas’s, and though his mentor was now dead, McClernand retained considerable political stature as the leading Democrat in Illinois. His gifts of oratory brought in significant numbers of recruits in the Midwest for service on the Mississippi, to which he was sending formed regiments, and this success brought him a commission as brigadier general from a grateful Lincoln. McClernand had his own ambitions. He recognised the political advantage to be won by pursuing a successful military career and, though his military experience was limited to a few weeks’ service in the Black Hawk War, he unfortunately believed that he was a field commander of great talent, at least equal to Grant, and set out to get an independent command in the army and lead it to victory. Moreover, McClernand had his own line of communication to Halleck, the general in chief, and enjoyed the favour of Lincoln. He began by persuading Halleck in Washington to issue him an order that appeared to give him an independent mission in the West and then to take charge of Illinois regiments as they were raised and sent south. The regiments joined Grant’s army, but McClernand exploited ambiguities in Halleck’s communications to make it appear that they were forming for an independent operation against Vicksburg.

Grant puzzled over the McClernand problem throughout October and November 1862, discussing it with Sherman in a series of cases but coming to no conclusion. McClernand was cunning, never openly challenging Grant’s authority but appealing in turn to Halleck and to political supporters in Illinois and other western states in a persistent attempt to enlarge his freedom of action. On paper he had scraps of authorisation to justify his insubordination, all of which he exploited shamelessly, but ultimately he was clutching at straws. He won none of the freedoms to which he aspired, and he lacked altogether the gifts of generalship he proclaimed to possess. Grant arranged to trammel him by reorganising the Army of the Tennessee into four corps and giving command of a fifth, the Thirteenth, to McClernand, thus exactly defining his powers. McClernand nevertheless continued to behave as if he were a fully fledged army commander and to correspond with Halleck and Lincoln. Fortunately Halleck, though no friend of Grant, was a stickler for military propriety and eventually tired of McClernand’s machinations. Finally, in June 1863, McClernand went too far. In defiance of an army order forbidding subordinates from writing to the newspapers without permission, he published a self-congratulatory despatch about his actions at Champion’s Hill in an Illinois newspaper. Grant at once relieved him of command, bringing his extraordinary career as a self-appointed leader of men to an end. He had certainly done nothing to advance the capture of Vicksburg, which throughout the early summer of 1863 remained beyond Grant’s clutches.

The Vicksburg problem, though exacerbated by the quarrels over command, was fundamentally a geographical one. By the summer of 1863, Vicksburg was a mighty fortress, made so by the terrain that surrounded it and by the earthworks its Confederate garrison had built. The Walnut Hills, on which Vicksburg stands, are steep and in 1863 they were cut by many deep, wooded ravines. Their bottoms were choked with dense brush and cane, their sides, sometimes forty or fifty feet high, overgrown by standing timber, from which fell dead trees which frequently formed natural abatis—tangled obstacles with sharp projections to injure and impair the progress of attackers as they passed through. The defenders had also formed many artificial abatis, tree trunks pierced to take sharpened stakes, all lying about the approaches to Vicksburg’s defences.

A European fortress or an American fortress in the East would have had its surroundings altered to make “dead ground” and provide fields of fire across a smooth glacis which could be swept by artillery fire and musketry. The nature of the ground and the abundance of vegetation at Vicksburg made the construction of such a glacis impossible. Both, however, contributed greatly to the strength of the earthworks. Around the enceinte, or enclosing wall, stood a number of strong-points, artillery platforms, redoubts, strengthening features, redans, and lunettes, all terms derived from the international vocabulary of fortification science, largely French in origin, which was taught meticulously at West Point. These terms were to feature particularly in Grant’s 1863 siege with the 2nd Texas Lunette, the 3rd Louisiana Redan, the Stockade Redan, the Railroad Redoubt, all named after the unit that had built or garrisoned them or after a nearby feature. The theory of the attack of fortresses prescribed an advance by infantry on the outer defences and walls, in an attempt to enter by storm, and, if that failed, a deliberate siege, by digging and bombardment.

The fortified city of Vicksburg, under the command of General John C. Pemberton, commander of the Department of the Mississippi, was therefore very strong, but even more important than the strong-points and batteries in protecting it against Union attack was the nature of its surroundings. In December Sherman attempted an assault against Vicksburg from the rear, at Chickasaw Bluff. The piece of ground chosen to mount the assault, the only one available, lay across the Chickasaw Bayou. It was a narrow triangle which Sherman’s men had to enter from the apex, and little dry ground could be found. Several assaults were made between December 27, 1862, and January 3, 1863, but the defenders outnumbered the Union attackers and were supported by artillery. Union losses eventually totalled 208 killed and 1,005 wounded against Confederate losses of 63 killed and 134 wounded. Sherman was obliged to withdraw his force. It had been defeated by geography, despite all the engineers’ efforts at bridging and pontooning.

The land around Chickasaw Bayou was typical of the whole lower Mississippi Valley, which Grant described as “a low alluvial bottom many miles in width … very tortuous in its course, running to all points of the compass, sometimes within a few miles.” There is high ground, the Vicksburg bluffs on the east bank, but the banks are generally low-lying and marshy, cut in many places by the bayous which are the distinctive feature of the river, shallow backwaters, drying out in summer but flooding in spring. Navigation was very difficult since the river and its tributaries and seasonal waterways were overhung by dense vegetation which had often to be cut if a vessel was to make headway. The meanders of the great river and of its subsidiaries were as convoluted as those of any river elsewhere in the world, often of hairpin form and forcing navigators to voyage long, wasted distances to advance in the desired direction. Adding to Union difficulties during the Vicksburg campaign was the summer climate—hot, humid, and disease-bearing, because of the dense insect life.

Grant had tried to march south on Vicksburg down the east bank of the Mississippi in November-December 1862, using as his line of supply the Mississippi Central Railroad, which led into Kentucky. Confederate cavalry raids, however, conducted by Forrest and Van Dorn, wrecked his forward base at Holly Springs, northwest of Vicksburg, and forced him to abandon the effort. He then reverted to the riverborne scheme, from several directions, including efforts by Sherman and McClernand. He called the components of his scheme “experiments,” which indeed they were since he had no assurance that any would succeed and in all he was working in the dark in the highly uncertain circumstances of uncharted swamps, river loops, and muddy, inundated backwaters. His idea was to get forward by cutting canals that would allow his gunboat fleet, with its transports, to pass from above Vicksburg to the Mississippi’s main stream below the city without coming under fire of its batteries. He had tried re-engineering the Mississippi Valley first in the summer of 1862 but despite several months’ digging had eventually had to abandon the attempt, because no end to the work came into view. In the winter he made four more attempts.

The first was an effort to complete the canal begun the previous summer, which cut across the neck of ground surrounded by the meander below Milliken’s Bend, one of the major navigable reaches of the great river above Vicksburg. Rising waters of the spring floods eventually threatened to drown the diggers, who belonged to Sherman’s corps, and the effort had to be abandoned again. The second was an attempt at Lake Providence, fifty miles above Vicksburg, from which diggings were to allow gunboats to reach the Mississippi’s main course 400 miles below the city and thence, by a roundabout route through swamps and backwaters, to get to the vital dry ground in its rear. The troops were supplied by the corps led by General James McPherson. He was an engineer officer whom Grant had identified as a highly effective combat commander. Lake Providence defeated his engineering talents, however. The route was impeded by huge trees rooted on the waterway’s bottom, which had to be sawn through. Months of that sort of labour, together with digging and dredging, dispirited both McPherson and his soldiers, to a point where the project had to be abandoned, as the Milliken’s Bend had been. The third and fourth attempts were to dig and clear navigable channels through what was called the delta of the Yazoo, in fact a bewildering complex of waterways joining the Yazoo River to the Mississippi above Vicksburg, from which by altering water levels by blocking holes in the Mississippi banks it was hoped to reach the Tallahatchie River and then the lower reaches of the Yazoo, which gave on to the northern approaches of Vicksburg. The staff officer in charge was so afflicted by the mental ordeal of the engineering prospect that he began to show evidence of a breakdown. His troubles were heightened by Confederate felling of trees across the Yazoo, which made the waterways impenetrable to gunboats. At this stage the campaign resembled less a river war than an expedition through subtropical forest, so dense and intertwined were the branches of the trees lining the route. The attempt was defeated by the d ensity of bankside vegetation and the complexity of the waterway’s course, and was eventually driven off by the guns of the hastily built Confederate Fort Pemberton.

Three months were spent on these fruitless and laborious engineering efforts. Grant’s critics in the East complained that he was wasting time and gaining nothing. Grant was resistant to criticism, having remarkable confidence in his own judgement; he claimed that his “experiments” kept John Pemberton, the Confederate commander of Vicksburg, off balance. He must, however, have been concerned about the effect of these operations on his troops, who were living in depressing, waterlogged conditions and forced to perform a great deal of heavy labour for no detectible outcome.

By early April 1863 Grant was in despair. Every effort he had made to get the Army of the Tennessee onto dry ground on the east bank of the Mississippi, from which he could mount an attack to capture Vicksburg, had been frustrated. Then a new idea came to him. If unsuccessful it would have dire consequences. If successful, however, it might well abolish all his difficulties and offer the prospect of complete success. Grant was not deterred by risk, and all his experience in the war thus far had fed his appetite for boldness. Unlike McClellan and Halleck, he was not encumbered by theory or by high military knowledge. He was thus not hampered by fears of cutting himself off from his base, which was precisely what he now intended to do. His base and his army were above Vicksburg. He proposed to transport his force to a decisive point below Vicksburg. What prevented him making a junction of ships and troops was the fourteen miles of guns lining the banks of the Mississippi on either side of Vicksburg, to which the soldiers could not be exposed without fearful loss. The ships might run the risk, however, if sailed by surprise, at speed and under cover of darkness. That was the essence of Grant’s plan. He would march his army farther down the west bank, to a point where, if the fleet arrived, a crossing could be made by steamer to dry ground on the east bank near Vicksburg itself. Fitz-John Porter’s fleet would meanwhile be protected and prepared to withstand heavy gunfire. Then, under cover of the night, it would run the batteries from north to south, to meet the troops at the chosen crossing place below Vicksburg. He would thus be placing himself behind enemy lines twice over, once by crossing to enemy territory, secondly by leaving the enemy’s main force in fortified positions athwart his line of communication and supply. Grant was determined not to be intimidated by the risks or the unorthodoxy of his intentions. Once on the Mississippi’s east bank, he would live off the country, carrying only ammunition and taking food and fodder where he found