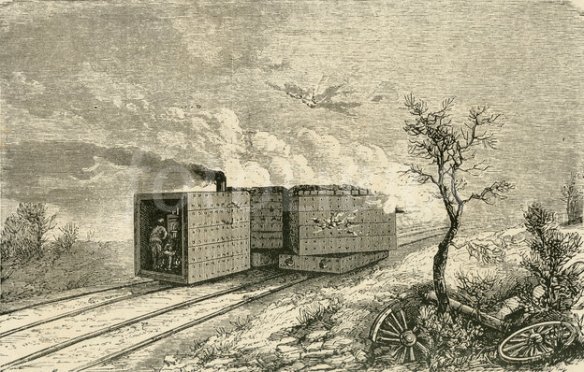

Armour-plated railway trucks used in 1870 during the Franco-Prussian War.

Those in France emanated, fan-like, from Paris, while the Prussian/German lines ran mostly on a north-south or east-west axis. In terms of density, the railways were about equal, with Prussia having the fourth most dense in the world and France the fifth. Both types of railway, too, could be harnessed to military objectives, but the east-west lines in Germany proved to be the most important. After the war, both sides accused the other of having constructed their railways with the aim of facilitating war. They were both right to some extent. In neither country did military objectives determine the shape of the network but in both they played a significant part in their development, through negotiation, lobbying and, ultimately, money.

In France, where half a dozen large railway companies had emerged in the 1850s, the railways were privately operated but their construction was supported at times with substantial state investment. The routing of new lines was governed by commissions mixtes consisting of both public and private interests but there were several instances where the Army determined the route of a railway. However, military interests were by no means always paramount as three-way rows developed between the companies, eager solely for profit, the Ministry of War, pushing for the most militarily strategic route, and the Ministry of Finance, worried about the cost of deviating from the commercial solution sought by the private sector.

The same considerations were being assessed over the border in Prussia, by the same players. Military advisers wanted rail lines built under the protection of fortresses, at a safe distance from frontiers and on the ‘opposite’ side of waterways – in other words, the bank furthest from the likely enemy, whose identity was known to both sides long before the start of the war. Money, too, was often a deciding factor, though the military clearly won the argument over the construction of several lines, notably the Ostbahn, which could take troops to and from the north-east.

The Prussians, in fact, were at a disadvantage because they had a far greater number of railway companies, under different state administrations, and there was therefore far less uniformity in the system. The Minister of Railways in Saxony complained rather wittily that it would be ‘to the general good in peacetime, and of benefit to the military man in wartime, if the superintendent met at Cologne was dressed like the superintendent at Köninsberg, and if there was no danger of a Hamburg station inspector being taken for a superintendent of the line by somebody from Frankfurt’. Rather more alarmingly, he added that there were parts of the network on which a white light meant ‘stop’ and others where it signified ‘all clear’, a real risk to the safety of people travelling on the system.

In the run-up to the war, there was widespread feeling in Prussia that the French had the better railways. That was backed up by compelling evidence in a pamphlet, published as late as 1868, by an anonymous Prussian officer who concluded that ‘the overall French [railway] performance exceeds the Prussian by far’. He cited the fact that only a quarter of Prussian lines were double-tracked, compared with over two thirds in France, creating far greater capacity. Moreover, he found that French stations were roomier, allowing faster loading and unloading and that the French had more rolling stock. He also suggested that the domination of the system by half a dozen large companies made it more unified with greater standardization of equipment.

Meanwhile, in France, senior officers who were eager to stir up hostile opinion against Prussia were warning that the French railways were inadequate to the task of defending la Patrie and that the Prussians had the better system. In fact, neutral observers such as van Creveld, the logistics expert, suggest that the French system was better: ‘On practically every account, the French railway system in 1870 was actually better than the German one.’ Nevertheless, even though the anonymous Prussian officer was right, the difference in the two systems would not prove decisive because the French were ultimately let down by their administrative arrangements.

In the late 1860s, as war drew closer, both sides attempted to tailor their railways to the needs of the coming conflict. Moltke was, again, lucky. He had a counterpart in France, Maréchal Adolphe Niel, the Minister of War, whose ‘intentions were quite similar and his vision no less lucid’. Niel, like Moltke, attempted to reorganize the railways to ensure that in the event of war, they would be under central military planning. In this he was supported by his sovereign, Napoleon III, but his reforms stalled in the face of resistance from conservative elements within the government. However, before that opposition could be overcome, Niel died. It was to prove a most untimely death which left a series of half-introduced reforms that would only add to the chaotic situation on the French side after war was declared. Without a man of Niel’s drive to push through change, the central commission he created, which was essential to the military’s ability to take control of the railways in wartime, was more or less forgotten and consequently was not in a position to be activated when war commenced.

In Prussia, the whole approach to war was more scientific and thorough. Moltke had reorganized the Prussian general staff, taking on highly trained military personnel drawn from the cream of army officers. Nothing was left to chance. There was endless analysis and planning, with railway and logistical issues being accorded high priority, and the whole approach was completely unlike the military organization of any other European nation. Nowhere else was there this emphasis on a scientific approach to warfare. This resulted in a bizarre political structure with an army that held a place of almost feudal status in society being supported by a highly technocratic and effective machinery.

As part of this process, Moltke quietly introduced a key reform affecting the railways. The translation of the report written by McCallum on his experience of running the railways for the North in the American Civil War was influential in convincing the Prussians that they must adopt the same structure. On this basis, Moltke was able to push through a reform enabling the military to strengthen its control over the railways, in particular those running on an east-west axis. He created a central committee of civil and military officials attached to the main railway office in Berlin to co-ordinate mobilization in the event of war. Even more crucially, for every major east-west railway across the territory of the North German Confederation – the area effectively controlled by Prussia after the 1866 war – he created individual line commissions controlled by the military which reported to the general staff of the central committee in Berlin. According to Allan Mitchell, the concept was crucial to the war effort because ‘this arrangement removed the principal obstacle to rapid troop movement: the necessity of crossing several state borders or of using the tracks of private companies’. Once war was declared and these commissions took control, it became possible to move soldiers long distances without changing engines or personnel, effectively giving the military control of the railways.

The line commissions remained inactive until the outbreak of war, when their first task was to issue emergency schedules to the key stations along the line. These schedules, which had been prepared in advance, were far more detailed and sophisticated than a simple timetable, setting out precisely the composition of each train, the number of men to be moved and even refreshment stops: ‘The execution of these schedules was to be so precise that many trains would be able to make connections en route, dropping and attaching cars to ensure that units would be complete, in their order of battle, when their trains arrived at the concentration areas.’

The war was actually declared by the French, the culmination of years of tension between the two sides over a variety of issues. The actual casus belli was obscure in the extreme, the candidacy of Leopold, a prince belonging to the Hohenzollern family, the rulers of Prussia, for the throne of Spain, which had been rendered vacant by the Spanish revolution of 1868. Under pressure from Napoleon III, who did not want France to be encircled by a Spanish-Prussian alliance, the candidacy was withdrawn but then the French emperor overplayed his hand, by trying to extract a promise from the Prussians that a Hohenzollern would never sit on the throne of Spain. Bismarck, who had put forward Leopold’s candidacy in the first place, then manipulated the situation by publishing the French demands in an edited form to inflame passions on both sides of the border. Bismarck’s intentions were clear. He felt he needed a war to guarantee the unification of Germany under Prussian control and had long worked towards this outcome. Napoleon, a foolhardy emperor with none of the nous of his illustrious namesake and uncle, was rash enough to declare war on 19 July 1870 despite the thinness of his cause and the fact that Prussian forces were likely to be at least as strong, if not stronger, than the French. He had sprung the trap set by Bismarck, who later, in his memoirs, wrote: ‘I knew a Franco-Prussian war must take place before a united Germany was formed.’

Napoleon’s cause was imperilled right from the outset by the chaotic mobilization of the troops on the French side. It was not the fault of the railway companies. Already, four days before the official outbreak of war, the five big main-line companies – Est, Nord, Ouest, Orléans and Paris-Lyon – had been effectively taken over by the military as they were ordered to place all their equipment and personnel at the disposal of the war ministry. All freight and most passenger services were cancelled, the number of telegraph operators doubled and military timetables distributed. Having already made contingency plans, by the next day the Est Company had prepared the first troop train, which was ready for despatch by 5.45 p.m., but the chaos that was to dog the whole French mobilization was already evident. The troops, who were accompanied by the same sort of enthusiastic crowds who were to greet their successors heading for war in 1914, with cries of ‘À Berlin’, had arrived at 2 p.m. only to find that the train was not due to depart for several hours. As a result, they did what such groups of men invariably do: drank their way around the local bars and caused mayhem. By the time the besotted soldiers arrived back at the station, many were collapsing from the effects of alcohol and, more seriously, had lost or given away their ammunition often as ‘souvenirs’, though much of it was later claimed to have supplied the revolutionaries in the following year’s Paris Commune (although that sounds like fanciful military propaganda).

This was a portent of things to come. Sure, nearly a thousand trains were despatched from Paris over the next three weeks, carrying 300,000 men and 65,000 horses, as well as countless guns, ammunition and supplies. Moreover, the French got to the frontier first. After a mere ten days, 86,000 men had reached the border, while hardly any Prussian soldiers were there to face them on the other side of the Rhine. However, the bare statistics mask an incompetent and ill-organized process that would seriously handicap the entire French war effort. Instead of the tightly planned schedule prepared by the Germans, French regiments were split up because they arrived piecemeal at the stations and men separated from their own commanders were often reluctant to take orders from officers on the train from another regiment. Some trains were despatched half-full, because of the non-arrival of a company, while others were overloaded as men who had missed their regimental train piled onto the next one. The unwillingness of officers to take control of the boarding and detraining of their men, as required by the regulations, and leaving it to the poor overworked railway officials, added to the confusion and delays. Systems to unload trains might not have been worked out properly, but measures to ensure the provision of coffee to the men at stations with the help of the steam from the locomotive as a kind of improvised espresso machine had been set out in great detail: ‘A receptacle of at least 150 litres is to be taken, in which sugar, coffee and water are placed, with each ration of 24 grams of coffee and 31.05 grams of sugar [it is not explained how such precise measurement can be made!] being allowed 42 centilitres of water. By means of a copper tube of diameter 0.012 metres fitted to a locomotive pressure gauge, a jet of steam is directed into the receptacle, with the tube deep in the water so as to agitate all the liquid. The operation is finished when the steam no longer dissolves…’

The momentum gained by having been the first to the border was, therefore, quickly lost, and any possible advantage for the French foregone. An early analysis of the use of railways by a Captain Luard written four years after the war sums up the French failings neatly: ‘In a fortnight, from the date of the order for mobilisation being given, the Germans placed 15 corps d’armée complete on the frontier, and did it methodically, so that everybody arrived at the right place at the right time, whereas the French sent everybody labelled À Berlin and much confusion resulted when they arrived at the terminus of the line. The German organization appears to have been more perfect throughout than that of the French, and the results were consequently more successful.’ Pratt, the original historian of the railways in war, is scathing about the French effort on the railways, pointing to ‘the absence of any adequate organisation for regulating and otherwise dealing with the traffic, so far as concerned the military authorities themselves’. A French general complained after the war: ‘you could see your railway trains encumbered by men crisscrossing their way in all directions and in all parts of France, often arriving at their destination just when the corps to which they belonged had left, then running after this corps, only to catch it up when it was beaten, in retreat, or besieged in an inaccessible fortress.’

The confusion on the ground was matched higher up the command chain. Because Niel’s idea of an overriding military commission in charge of the railways had failed to take root, orders for running trains came from everyone and everywhere ranging from the Ministry of War and its various bureaux to local authorities and préfets, right down to officers and non-commissioned officers seeking to prioritize their needs over others. All of these were not averse to threatening railway officials with dire consequences should they disobey, however impractical their orders or trivial their requests: ‘the assumption that trains could be made to operate simply by issuing orders was never abandoned by some high officers, even after painful experience’.

Orders would be countermanded and then reinstated with great frequency. The accumulation of wagons and matériel was legion and their use as storage was widespread, blocking up sidings and preventing their re-use by other parts of the Army. Officers took advantage of the lack of central command to retain wagons both to provide storage for their supplies and to transport their equipment should their regiment be moved. This, of course, was the obvious consequence of the failure to have an overall control system. The needs of one part of the Army were not necessarily concomitant with the efficient pursuit of the conflict: an obvious conclusion, but one which the military command in 1870 seemed unable to comprehend.