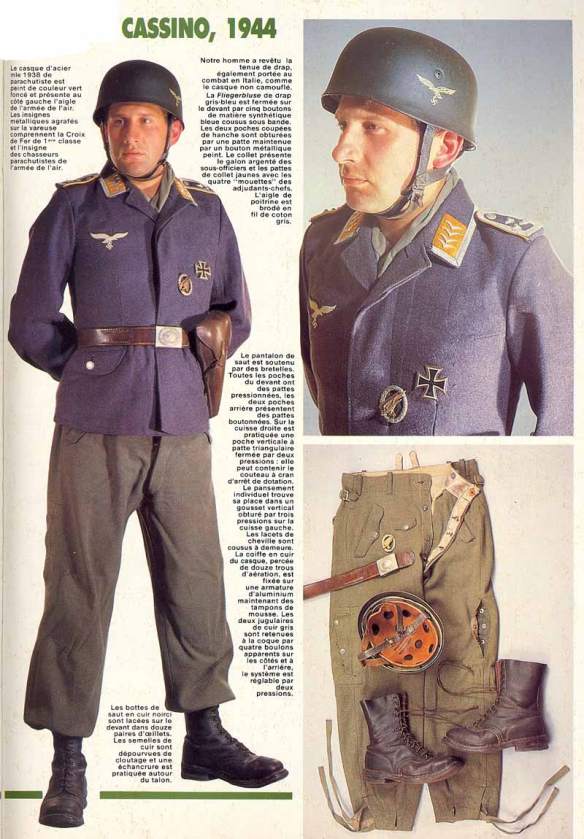

Fallschirmtruppen were issued a variety of uniform components of different colors. These were commonly worn mixed with little consistency. This Jager (private) wears the paratrooper’s blouse (Fallschirmjagerbluse), a waterproof protective jacket known to paratroopers as the Knochensack (bone-sack). These jackets were commonly issued in gray-green, tan (for tropical areas), and two camouflage patterns, ·’splinter” and “splotched” (aka “water”). All of these were found in Italy and often mixed within units. It is worn over the blue-gray Fliegerbluse (flyer’s jacket). The Waffenfarbe of the Fallschirmtruppen was gold-yellow, the same as for flying troops. The gray-green loose-fitting overtrousers are worn over the blue-gray flyer’s trousers as a means of camouflage and additional weather protection. They were also made in sand-color. The dome-like paratrooper’s steel helmet (Fallschirmhelm), known as a Nussschale (nutshell), was similarly issued in a variety of colors: gray-green, blue-gray, and sand. Cloth helmet covers were also used in green, sand, tan, and camouflage fabric. The lace-up paratrooper’s boots proved to be useful footwear in Italian mountains. Slung over his neck is the eight-pocket bandoleer for 20-round magazines for the 7.92mm FG 42 Fallschirmjagergewehr automatic rifle. These were made in gray-green, sand, and camouflage colors. It was originally envisioned that the FG 42 would replace the bolt-action carbine and the MG 34 machine gun in Fallschirmjager units. Only 6,000 were produced, in two versions. They were unevenly distributed with two to four per platoon.

The most formidable formation in Italy was the Luftwaffe’s 1st Fallschirmjäger Division. Following the battle for Crete in May 1941, Hitler refused to authorise any further large-scale airborne operations due to the high casualty rate. His paratroopers subsequently became élite infantry, serving in Russia, North Africa, Sicily, and Italy. From the start, they were a volunteer-only force, with a high drop-out rate in training. Leutnant Hermann Volk, who fought at Cassino, recalled how on the first day of training in Pomerania recruits had to stand to attention and fall forward towards a comrade standing opposite, but without stumbling: `That was a true test of trust, for the many who put out their hands or legs to prevent injury were immediately rejected as unsuitable.’ Designed to land and fight in small groups, with limited prospects of resupply or reinforcement, Fallschirmjäger were trained to be highly resilient, resourceful, act without orders and to expect to tackle overwhelming odds. Though light in artillery, paratroops were reliant on large numbers of automatic weapons and grenades, and usually encountered as small, kampfgruppen (all-arms battle groups) organised from any available troops. They liked the nickname of `Grüne Teufel’ (Green Devils) awarded to them by their Allied opponents in Tunisia and Sicily, on account of their distinctive three-quarter-length camouflaged parachute smocks. An excessive esprit de corps was encouraged, and a disproportionate number of them gained high decorations, or fell in battle.

After landing at Salerno on 9 September 1943, the Allies drove north against the defending German Fourteenth Army. The Italians were out of the picture as they had surrendered to the Allies on the eve of the invasion. The US Fifth Army was on the western side of the central mountain range extending the length of the boot of Italy. The British Eighth Army was on the eastern side of the mountain spine. The Germans prepared a series of defensive lines, making excellent use of the rugged terrain for fortified positions and obstacles. Each defensive barrier would be bitterly fought over before the Germans withdrew to the next prepared line. The cost was high to the Allies in men and materiel. In September the German plan was to buy time for the building of the Winter Line, also called the Gustav Line, south of Rome. It would be built on particularly defendable terrain. Not just the heights were incorporated into the defense, but rivers as well. Some valleys and other low areas were flooded. The Winter Line would be reinforced by the coming winter weather, which would greatly hamper Allied actions, movement, logistics, and air support. The Allied plan was to reach Rome in October 1943, which was far too optimistic.

The Winter Line was reached by the Allies in December 1943 and even breached in the east by the British. The western portion of the line though was the most heavily defended sector and blocked the road to Rome. The brutal winter arrived and brought the Allies to a near standstill. The linchpin of the Winter Line was Monte Cassino, near its center, and the surrounding terrain. Four battles would be fought to breach the line and take Monte Cassino between 17 January and 18 May 1944. The participants would represent the full spectrum of the Allied nations. To support the attack on the Winter Line a second Allied landing was made at Anzio on 22 January. This was northwest of Monte Cassino and only about 25 miles southeast of Rome. It soon became bogged down against determined German resistance. It did have the benefit of drawing troops out of the Winter Line and reducing German reserves to counter any breakthrough.

The first attack on Monte Cassino, commencing on 17 January 1944, was led by II US Corps and supported by the French Expeditionary Corps. Despite valiant efforts the attack failed and the US troops were relieved by the New Zealand Corps (which included an Indian division) on 11 February. The second battle began with the controversial bombing of the great Abbey of Monte Cassino on 15 February by the US Army Air Forces at the request of the Indian division commander and New Zealand corps commander. It was believed that the 150-foot high, 10-foot thick masonry walls and the deep vaults provided the Germans with an impregnable fortress. To this day it has not been clearly determined if it was actually occupied by the Germans. The New Zealand and Indian attack began on 17 February and had failed by the next day. The Allies now determined that the winter conditions and the stubbornness of the defense necessitated waiting for more suitable weather. (The Germans considered the first and second battles together to be the “first battle” and called the third battle the “second.”)

The first and second battles had seen attempts to force the Rapido River south of Cassino town and a “right hook” to the north of Monte Cassino. The third battle would be executed by double thrusts north of Cassino town. The New Zealand Corps would lead the attempt, this time reinforced by a British division. The attack began on 15 March and was initially successful, but a German counterattack cost the Commonwealth troops the initiative and the attack was called off on the 20th. It would be almost two months before the fourth and final battle for Monte Cassino. Allied reinforcements were desperately needed and fair weather was essential for air support, directing artillery, logistics movement, and to allow effective tactical maneuver by ground troops and vehicles. Additionally, the cold and wet Italian winter had exhausted and numbed attacking troops, who quickly lost their effectiveness.