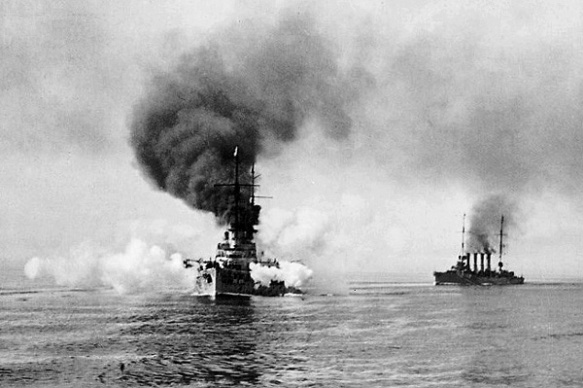

Goeben and the Breslau

MAS boats-fast motor torpedo boats. Italian Torpedo Boat MAS 15 racing away from the already dramatically listing Austrian battleship Szent István on 10 June, 1918.

The Italian decision to remain neutral on the outbreak of the war, based on the strictly defensive nature of the Triple Alliance, relegated these naval plans to the dustbin of history. The situation swiftly evolved to the advantage of the French but the preoccupation of the French commander-in- chief with defending the French convoys may well have contributed to the ability of the Goeben and the Breslau to elude British warships and escape to the Dardanelles where their fictitious sale to the Turks took place. Regardless of their strategic implications in the Black Sea and their role in helping to engineer the Turkish entry into the war, the ships were now outside the Mediterranean equation. They would only re-enter it briefly in January 1918 and the results were unfavorable. They sank two British monitors but Breslau was sunk and Goeben narrowly escaped destruction. The French, who received command in the Mediterranean in August 1914, were unchallenged masters of the sea and Austrian forces were too weak to challenge them. The Austrian fleet was essentially bottled up in the Adriatic. On the other hand, the French fleet could not get at the Austrians and had to content themselves with a blockade across the entrance of the Adriatic with periodic sweeps to escort ships carrying supplies to Montenegro. The French were hampered initially by the lack of a base at the entrance to the Adriatic and had to make use of distant Malta. Submarines would soon make the entry of large ships into the Adriatic too hazardous.

Italy’s entry into the war in May 1915 made the French fleet essentially a reserve fleet. Moreover, the Italians were adamant that only an Italian admiral could command in the Adriatic. This meant that two battle fleets were employed watching the Austrians: the Italians at Taranto and the French at first at Argostoli and eventually at Corfu. Here successive French commanders-in-chief trained for a fleet action that never occurred. The naval convention accompanying Italy’s agreement to enter the war also specified that a flotilla of French destroyers and submarines would work with the Italians at Brindisi. The actual number varied according to French requirements, especially after the beginning of the Salonika campaign, and the relationship was far from cordial. It was obviously the arrival of German submarines at Austrian bases that presented the most serious challenge to the Allies at sea. The French found that they were ill prepared for this type of warfare and had recourse to Japanese shipyards for a series of 12 destroyers and also purchased over 250 trawlers from allies and neutrals for anti-submarine duties.

The fundamental interests of the French and the British diverged in the Mediterranean. The French were understandably preoccupied with protecting the north-south routes between France and their North African possessions, as well as supporting the Salonika expedition about which the French were more enthusiastic than the British. The British were more concerned about the east-west routes through the Mediterranean to Egypt and the Suez Canal. The fact that the British had such important trade interests in the Mediterranean and far greater numbers of craft suitable for anti-submarine warfare meant that the British, step by step, took over direction of the anti-submarine war in the Mediterranean, although the theoretical French command remained.

The French found after the war that their situation vis-a-vis the Italians in the Mediterranean had altered to their disadvantage. At least part of the problem stemmed from the cautious policy of the Italians towards their battle fleet. Even during the period of Italian neutrality the Capo di Stato Maggiore Thaon di Revel insisted that, whatever operations were undertaken against the Austrians in the Adriatic, such as support of army operations against Trieste, they should never run the risk of putting their battleships in danger of mines or torpedoes and should seek to cause major damage to the enemy while suffering the minimum. This would be accomplished by the aggressive action of light craft and torpedo-boats while major Italian warships would be preserved for action against their peers. This did not mean the Italian battle fleet would never fight, it would, but only against the Austrian battle fleet if and when the Austrians came out. These fundamental lines would not alter, although the Italians certainly considered the possibility of intervention by the fleet in the upper Adriatic. Painful losses to submarines after Italy entered the war imposed further caution. There were plans for the seizure of certain islands off the Dalmatian coast and a landing on the Sabbioncello Peninsula (later taken up again by the US Navy in 1918), but the Italian Army was reluctant to divert forces from the campaign on land. The presence of the Austrian fleet at Pola as a fleet-in-being ready to intervene meant that heavy ships would have to participate and the potential gains never really seemed to equal the potential risks. The Italians did occupy the tiny and barren island of Pelagosa in the mid-Adriatic, only to abandon it in a relatively short time.

The relationship of the Italian Navy with its British and French allies was frequently a difficult one and seemed to worsen in 1917 and 1918. The Italians seemed constantly to be demanding assistance in ships and matériel yet were reluctant in British and French eyes to take risks or contribute to the anti-submarine effort by providing destroyers for convoys, while they jealously insisted on command in the Adriatic. The Italians, for their part, could argue that their efforts were not really appreciated, that they were the only ally in close proximity to a major enemy fleet since Pola was but a few hours’ steaming distance from the Italian coast. This forced them to divert numbers of light craft for the defense of Venice. Furthermore, it was foolish to risk large ships in the confined waters of the Adriatic where submarines and torpedo-boats could be more effective at less risk. The MAS boats-fast motor torpedoboats-were probably the major Italian naval success of the war. Moreover, the Italians had their own coastal traffic in the Tyrrhenian to defend, as well as their lines of communication to the Italian Army in Albania and Libya. There is no doubt, though, that the Italians bitterly resented their beggar status, the reliance on others for essential items such as coal and the sometimes scarcely veiled aspersions on their courage for failing to do what they considered foolish things. All of this would create a poisonous atmosphere in the aftermath of the war.