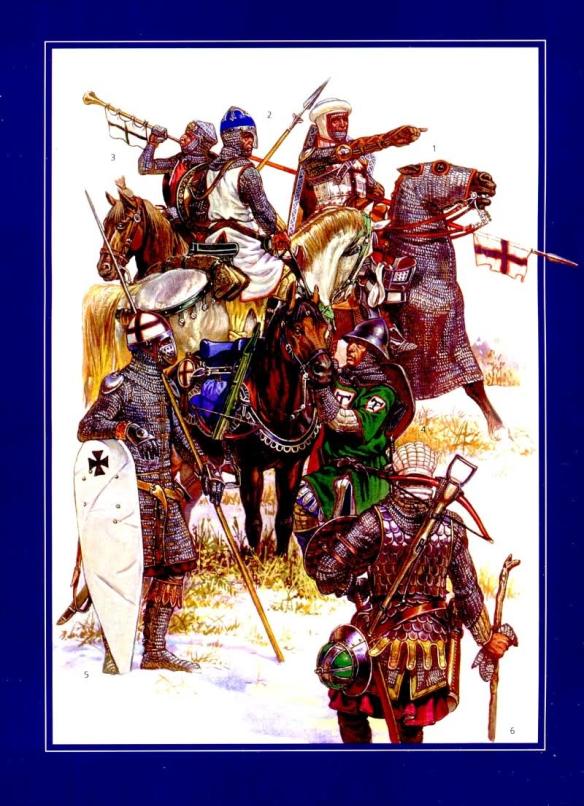

During the Baltic crusades against the heathen Prussians and Lithuanians, the Prussian branch of the Teutonic Order was not dependent on mercenaries, because this was a religious war supported not only by the Church, but also by the warlike European aristocracy including kings and emperors. The famous Reisen, the military expeditions to Prussia and from there into Lithuania, were for more than 150 years an important part of chivalric life in Latin Europe. One can find mercenaries who were not hired by the Order, but by pious persons in the Latin West who-for different reasons-could not travel in person to Prussia, but nevertheless wanted to participate in papal blessings and obtain absolution of sins. The situation changed and became complicated for the Order when war broke out with Christian Poland in 1327. As their new adversaries were not heathen, the knight-brothers could not count upon help from crusader armies and lost the battle at Płowce (Poland) in September 1331. Polish military technique and equipment (heavy cavalry etc.) was on a similar high level to that of the Teutonic knights. Now, for the first time, it was necessary for the Order to recruit mercenaries. Chronicles tell us the names of two of the mercenary commanders: Otto von Bergau from Bohemia and Poppo von Köckritz from Meissen. After a state of war for many years peace was finally concluded with King Kasimir the Great of Poland (1333-70) at Kalisz in 1343. In the meantime military enterprises against heathen Lithuania were carried on with the participation of crusaders.

When the Grand Duchy of Lithuania had been united with the Kingdom of Poland in a personal union under King Władysław Jagiełło (1386) and Lithuania, independently of the Teutonic Order, had been peacefully Christianised (1387) a new and much more dangerous situation arose because the mission of the Knights, i. e. the war against the heathen, could no longer be carried out de jure. The legal existence of the Order was from now on seriously questioned by its opponents, who proposed that the Knights should be removed from Prussia and used on other frontiers as a shield of Christianity against Tartars and Turks. According to Thomas Aquinas, heathens could be enslaved, but not Christians, and therefore the Knights were no longer permitted to enslave their many prisoners from the campaigns in Lithuania. These prisoners could be used in different ways, notably as settlers, in which capacity they contributed substantially to strengthening Prussia in a time of demographic crisis and economic recession in Europe, and to ensuring the advance of colonisation up to the year 1410. For these and other reasons, the Teutonic Order denied that the Lithuanians’ conversion was genuine and ignored the prohibitions on further military expeditions by the German and Bohemian King Wenceslas in 1394 and Pope Boniface IX in 1403. However, from now on, many crusaders stayed away from Prussia, and when conflicts with Poland increased towards the end of the 14th century, the Order had to look for an adequate substitute for the crusader armies. Money had to support religious arguments, and therefore it was necessary to hire mercenaries.

For many years this was no substantial problem for the Teutonic knights, because their Order was wealthy. As long as the conflict with Poland was essentially diplomatic, as it was in the years after 1386, the Knights could rely on long-term agreements of up to 10 or 15 years with the Pomeranian dukes of Wolgast, Stettin and Stolp, who got much money under the obligation to serve the Order in case of war. 7 The details of their service were fixed in contracts: the number of men and horses, the equipment, the payment etc. Similar agreements were also made with some Pomeranian nobles. As a matter of fact we have to regard these documents as a special kind of mercenary agreement. The dukes were eager to get the money, but later often neglected their duties.

As diplomatic negotiations between the Teutonic Order and Poland in June and July 1409 ended without any positive result, Grand Master Ulrich von Jungingen decided to declare war and undertake a surprise attack on Poland. On 6 August he signed a declaration of war, and ten days later three armies of the Order marched into northern Poland, the biggest of them into the province of Dobrzyń (German: Dobrin). The Knights’ troops, including many mercenaries, were victorious on all the fronts. Only one minor field battle had to be fought and was won, many castles, cities and villages were conquered, destroyed and burned and many people killed. The Poles were not yet prepared for war, but after some weeks an army gathered together, which marched against the invaders. After hard negotiations near the border a truce was concluded on 8 October to be kept until St John’s Day in 1410.

From now on, both sides prepared to continue the war after the end of the truce, which was later prolonged by ten days. This time the initiative was taken over by the Poles and Lithuanians under King Jagiełło and his cousin Grand Duke Vytautas of Lithuania. A big joint army crossed the border in southern Prussia with the intension of marching against Marienburg (now Malbork, Poland), the main castle of the Teutonic knights, but it was confronted by the Order’s army on the fields of the three villages of Tannenberg, Grünfelde and Ludwigsdorf, the Polish names of which are Stębark, Grunwald and Lodwigowo. Here the famous battle of Tannenberg was fought on 15 July 1410. A successful feigned flight of a part of the Lithuanian army was followed up by an attack by heavy Polish cavalry forces into the Order’s ranks, resulting in a disastrous defeat of the Teutonic knights. Grand Master, Ulrich von Jungingen, was killed in action. With the exception of a few strong castles which could withstand the following sieges, among them Marienburg, Prussia was occupied for some weeks until the Lithuanians and Poles withdrew voluntarily or were expelled by combined forces from Prussia, Livonia and the Reich, including many mercenaries. Peace was made on 1 February 1411 in Thorn. The battle of Tannenberg had changed the political constellation in east central Europe, considerably diminished the might of Prussia and opened the way for Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania to play a central role in this part of Europe until the end of the 18th century.

The Mercenary Service

During the war both sides engaged mercenaries. Those of the Poles came mostly from Bohemia and played an important role in the Tannenberg battle, as they, according to a reliable Polish source, had fought `victoriously and kingly’ (victoriose et regaliter). However, in what follows we will take a closer look only at those mercenaries who were recruited by the Teutonic knights. The war service of the Pomeranian dukes will be left aside.

One of the most famous episodes during the battle of Tannenberg was the attack by Luppold von Köckritz, a knight from Meissen, against the Polish king, in which he lost his life. Köckritz was not a mercenary, but a friend of Grand Master Ulrich von Jungingen and an ardent admirer of the Teutonic Order. He had joined the Knights’ army at his own cost. Some weeks before the battle he described the ideological and psychological problems of his aristocratic compatriots in a letter to the Grand Master. There he made a distinction between war against Lithuania and war against Poland: in case of war only against Grand Duke Vytautas, many knights and squires would serve the Order `for chivalry’, that is at their own costs. The implication of this is that they would only serve against the Poles as mercenaries. The same problem is alluded to two decades later, when Grand Master Paul von Rusdorf prepared for a new war against Poland and told the Order’s commanders in the bailiwicks in the Reich to send armed men and horses to Prussia at their own costs. The answer he got (in 1429) gave the following characteristic description of the situation: `In former times sovereigns, masters, knights and squires rode to Prussia for God and chivalry, but that was to fight against the heathens, and they don’t any longer regard it as that’. This is striking evidence that the Teutonic Order had now definitely lost its ideological basis and could only survive thanks to expensive mercenary recruitment and war service which was a constant dilemma for the knight-brothers until the Prussian branch of the Order was dissolved in 1525.