In the autumn of 1845 Frémont came on his second exploring expedition to California.

June, 1846-January, 1847

When the United States declared war on Mexico in May, 1846, the military strategy of President James K. Polk and his advisers was to occupy the capitals of the northern Mexican provinces and march on Mexico City itself. Polk hoped the two campaigns would result in a quick end to the war. He assigned the task of winning New Mexico and California to the Army of the West, commanded by Brigadier General Stephen Kearny. In the spring of 1846, Kearny assembled his forces at Fort Leavenworth. Under his command were three hundred regular dragoons and five hundred Mormon youths, led by Lieutenant Colonel Philip St. George Cooke, who had been recruited from their encampment at Council Bluffs, Iowa, where Brigham Young was making plans to move westward to Deseret. Kearny also was accompanied by a regiment of infantry and a train of wagons. Missouri frontiersmen and recruits brought the total personnel under his command to twenty-seven hundred.

The March to Santa Fe

On June 30, 1846, this army started for Santa Fe, following the Santa Fe Trail for eight hundred miles, first to Bent’s Fort on the Arkansas River and then southward into New Mexico. On the outskirts of Santa Fe, Kearny learned that three thousand Mexicans under the command of Manuel Armijo, the governor of New Mexico, had occupied a strategic canyon through which Kearny’s men would have to pass. Rather than risk a military clash, Kearny resorted to diplomacy, sending forward intelligence agent James Magoffin, who, acting on secret instructions from Polk, succeeded in convincing Armijo that he should flee southward.

Colonel Juan de Archuleta, Armijo’s second-in-command, proved more difficult and would not withdraw the Mexican Army until Kearny promised that he would occupy only part of New Mexico, leaving the rest to Archuleta. Kearny’s army then marched into Santa Fe without contest, but disregarding his promise to Archuleta, Kearny issued a proclamation announcing the U. S. intention to annex the whole of New Mexico. He promised the residents a democratic government and a code of law, and he named Charles Bent as governor. When settlers in southern New Mexico questioned his actions, Kearny took a detachment down the Rio Grande to ensure the loyalty of Mexican villages.

With the first phase of his campaign completed, Kearny continued his program by separating his army into three forces. One he left behind in New Mexico to hold the province. Another, composed of three hundred volunteers from Missouri under Colonel Alexander Doniphan, went south by way of El Paso to occupy Chihuahua City. Magoffin, sent ahead to ensure a peaceful occupation, was unsuccessful. Doniphan’s troops had to fight the Battle of Brazito before occupying El Paso, and they had to drive back a Mexican army of four thousand at Chihuahua City. Kearny had taken the third force of three hundred dragoons out of Santa Fe on September 25, 1846, and headed for California.

Kearny was accompanied by Lieutenant William Emory and other officers of the Topographical Engineers, who were making observations on the feasibility of wagon and railroad routes. The expedition moved rapidly down the Rio Grande and then west along the Rio Gila. There it encountered a detachment led by Kit Carson, bringing the news east that California was in the hands of the United States. Assuming that a military campaign would be unnecessary on the coast, Kearny ordered two-thirds of his troops back to Santa Fe and commanded the reluctant Kit Carson, now a lieutenant in the United States Army, to guide him and one hundred dragoons westward.

The division of Kearny’s force was fortunate for the interests of the United States, because the detachment returning to New Mexico arrived in time to suppress the Taos Revolt led by the disgruntled Archuleta, in which Governor Bent and other officials had been slain. The revolutionaries took refuge within the adobe church there, and U. S. forces had to storm the walls and kill many Mexican leaders before the revolt came to an end and U. S. authority was restored.

The Struggle for California

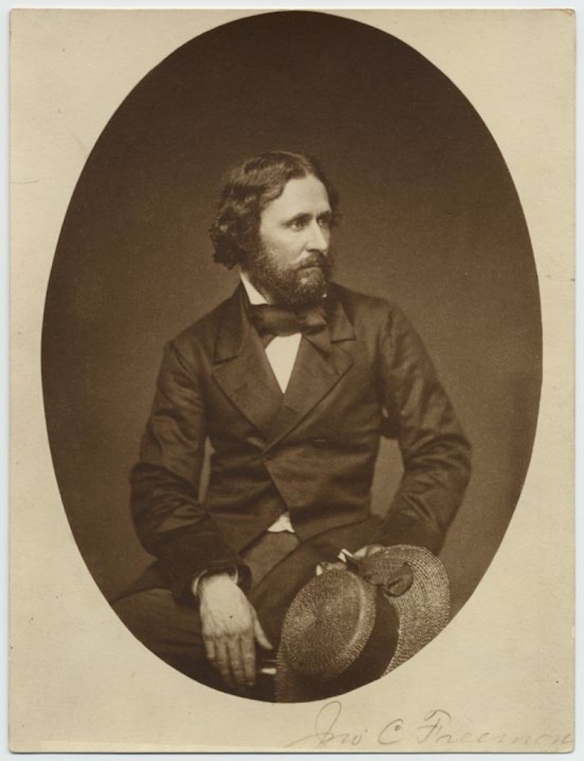

At the same time, the United States extended its authority to California. Before war had been declared between the United States and Mexico, Thomas O. Larkin, the U. S. consul in California, had hoped that he could effect a peaceful transfer of the Mexican province to the United States. Larkin’s hopes were dashed, however, by events surrounding John C. Frémont’s appearance in California between December, 1845, and June, 1846. Frémont had secured permission from Governor José Castro for his scientific expedition to winter in California on the condition that Frémont avoid coming near any settlements. Frémont’s failure to honor the agreement prompted Castro to demand Frémont’s departure from California. Avoiding hostilities temporarily, Frémont led his detachment slowly up the Sacramento River Valley until he was overtaken at Klamath Lake by Lieutenant Archibald Gillespie of the U. S. Marines, carrying confidential messages and papers from the U. S. government and from relatives. The exact contents of these communications have remained unknown; however, Frémont there upon returned to California, despite Castro’s order to leave, and made his way to the vicinity of Sonoma. There, in June, he immediately became involved in an uprising of settlers from the United States, a insurrection known as the Bear Flag Revolt, so named for a flag bearing the symbols of a red star and a bear, which the insurgents adopted as their standard.

Frémont’s national reputation as a hero in the conquest of California waned when the Bear Flag Revolt was assessed against the efforts of Larkin to secure California peacefully for the United States, and when it was learned that the war with Mexico-which prescribed the U. S. conquest of California- had been declared before the Bear Flag Revolt took place. Critics have censured Frémont for having provocatively endangered relations between the United States and Mexico at a time when Frémont could not have known of the state of war. Historians point out that the Bear Flag Revolt had little importance in the U. S. conquest of California, because Commodore John Sloat’s first official act of conquest was to sail into Monterey Bay and raise the United States flag over the customs house on July 7, twelve days before Frémont’s arrival in Monterey.

Events of the Bear Flag Revolt merged with the conquest by United States forces. The first stage of operations, from July 7 to August 15, 1846, resulted in the temporary occupation of every important settlement in California, including San Francisco, Sutter’s Fort, Monterey, and Los Angeles. It was news of this success that Kit Carson was carrying to the east when he met Kearny. Scarcely had Carson departed when a local revolt erupted in Los Angeles on September 22, and the United States troops under Gillespie were forced to retreat to the Pacific port of San Pedro, leaving southern California once again in Mexican hands. Commodore Robert F. Stockton, in charge of U. S. naval forces, left Monterey for the south.

Conquest

Meanwhile, the Mexicans, learning of Kearny’s approach to San Diego, had come out to meet him near present-day Escondido, California. In the ensuing Battle of San Pasqual, United States troops were mauled badly but managed to struggle on to San Diego. Kearny then joined Stockton’s forces in a successful march into Los Angeles. Frémont, in the meantime, marched down the California coast with deliberation. The Mexican leaders who had violated their paroles made at the time of the first capitulation were afraid of retribution at the hands of Kearny or Stockton, and so sought out Frémont in the mountains north of Los Angeles, where they surrendered at Cahuenga on January 13, 1847.

The conquest of the Southwest was at last complete. A bitter quarrel then ensued between Stockton and Kearny over who was in command in California. Frémont sided with Stockton, but Kearny appealed to Washington, D. C., and received confirmation of his authority. Diplomatic complications delayed the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo until February, 1848, more than a year after the fighting in the northern Mexican provinces had ceased. As a result of the treaty, the United States acquired all or portions of the future states of California, Nevada, Utah, Colorado, New Mexico, and Arizona. Native Americans and Mexicans passed under the suzerainty of the United States.