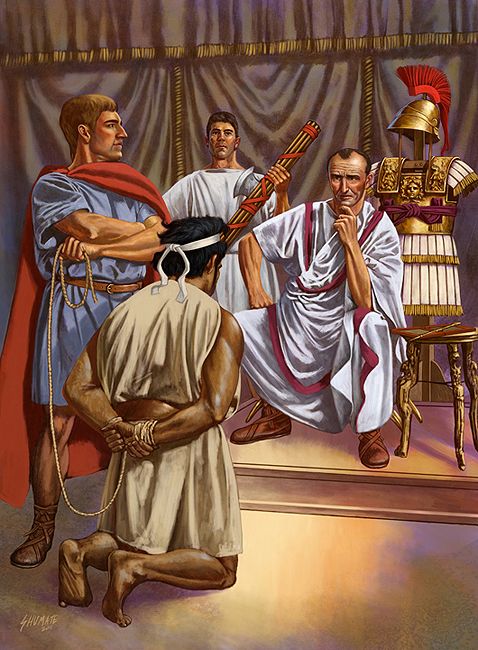

Marius captured Jugurtha, King of Numidia, and, after parading his captive around the streets of Rome he was thrown into the Tullianum prison, where he is said to have been starved to death.

A map of Numidia during the Jurgurthine War.

After the Second Punic War, Rome awarded their ally Masinissa, king of the Massyliis of Eastern Numidia, with the territory historically belonging to the Masaesyli of Western Numidia. As a client kingdom of Rome, Numidia thus surrounded Carthage on all sides, a circumstance which proved instrumental in provoking the Third (and final) Punic War. Masinissa died in 118, leaving his sons Adherbal and Hiempsal to contend with their cousin Jugurtha, illegitimate by birth but lately acknowledged by Masinissa and possessed of both military skill and boundless ambition.

Out of Africa

According to African studies scholars Harvey Feinberg and Joseph B. Solodow, the proverb, “Out of Africa, something new,” dates at least to Aristotle and was current in ancient Rome, where “new” meant something dangerous or undesirable. As A. J. Woodman points out, Jugurtha seemed to fit this stereotype perfectly. His first act after the death of his uncle Masinissa was to assassinate Hiempsal, who had insulted him on account of Jugurtha’s illegitimate birth.

In the history of the war prepared by Gaius Sallustius Crispis (Sallust) in the late 40s bc (where most of our information about the war comes from), Jugurtha appears ruthless and warlike, attracting the most aggressive followers so that, even though Adherbal had “the larger party,” Jugurtha had little trouble conquering or convincing one city after another. After one bad defeat on the battlefield, Adherbal fled to Rome, where he pleaded his case as the rightful king of a client country.

A City for Sale

Unquestionably, Adherbal held the better legal position, but in the Late Republic money spoke loudly, and Jugurtha-who dismissed Rome derisively as “a city for sale”-bribed his way forward until a Roman commission divided Numidia into halves, awarding Jugurtha the west and Adherbal the east. Sallust explains that while the east had the appearance of higher prosperity, thanks to an “abundance of harbors and public buildings,” in fact the west had the better value owing to its richer soil and greater population. Jugurtha gathered from this outcome that money could gain forgiveness for any aggressive action, and Rome’s commission had hardly left Africa before he began ravaging Adherbal’s territory. He finally trapped Adherbal in his capital at Cirta, though not before Adherbal had sent a message to Rome, pleading for aid; to save his city, Adherbal surrendered to Jugurtha, who killed him. In this instance, Jugurtha’s actions had far surpassed the power of bribery, and Jugurtha was surprised to discover that Rome had launched an army. For two years (112-110 bc), minor skirmishes ended mostly in Jugurtha’s favor, but the Numidian violated a truce established in 110 and set out to eradicate Rome’s presence in Numidia altogether. In 108 bc, a Roman army, commanded by Caecilius Metellus, drove Jugurtha into the borderlands after the Battle of the Muthul, but the wily and warlike Jugurtha harried them in a grueling guerilla war. Finally, in 106 bc, under the new commander Gaius Marius and his lieutenant Lucius Cornelius Sulla, the Romans ran Jugurtha to ground. The conclusion of the Jugurthine War firmly established Rome’s position in Northern Africa but more than that, it played a major role in the fall of the Republic. Marius’s reorganization of the army resulted in the establishment of a permanent, powerful army, loyal primarily to its commanders: this would contribute a great deal to the rise of Julius Caesar (Marius’s nephew) and the military expansion of the empire.

Marius’ Mules

Gaius Marius, who held an unprecedented series of consulships during the last decade of the second century BC, and who defeated first the Numidian kinglet Jugurtha and later the much more serious threat to Italy from migrating Celtic tribes, has often been credited with taking the decisive steps which converted the Roman army formally into the long service professional force of which the state stood much in need. As will become apparent, this is a considerable over-estimate of the scope-and results-of his work. Marius’ background is an important factor in ancient and modern judgements on his career, so that a brief description seems worthwhile. Marius was born in 157 at Arpinum, a hilltown of Volscian origin (now Arpino), stunningly positioned on the end of a narrow ridge in the western foothills of the Apennines, some 50 miles south-east of Rome. Though his enemies claimed that he was of low birth-the `Arpinum ploughman’ in one account-he almost certainly belonged to one of the town’s leading families. Marius first saw military service, probably as an eques serving with a legion, at Numantia, and is supposed to have attracted the attention of Scipio Aemilianus. Later he was a military tribune, and afterwards became the first member of his family to reach the Senate. A marriage in about 111 allied him with the patrician, but lately undistinguished, family of the Julii Caesares, which must mark his acceptance into the ruling circle at Rome.

JUGURTHA

Outside Italy attention turned to Africa, where the successors of the long-lived Masinissa, king of Numidia (who had fought as an ally of Scipio at Zama), contended after his death for supremacy. Jugurtha, a cousin of the leading claimants, outmanoeuvred his rivals as Rome looked on, but made the mistake in 112 of allowing the killing of some Italian traders. The Senate was forced to intervene: what had seemed at first a minor local difficulty now developed into full-scale warfare which a succession of Roman commanders were unable to control or were bribed to countenance. The catalogue of shame culminated in a total surrender of a Roman army, which was compelled to pass beneath the yoke, and withdraw within the formal bounds of the Roman province. The command now fell to one of the consuls of 109, Q. Caecilius Metellus, scion of one of the most prestigious families of the age, men whose honorific surnames (Delmaticus, Macedonicus, Balearicus), served as an index of Roman expansion during the second century. Additional troops were enrolled, and among experienced officers added to Metellus’ staff were Gaius Marius (a sometime protégé of the Metelli) and P. Rutilius Rufus who had served as a military tribune at Numantia, and who was to gain some reputation as a military theorist and author. Metellus’ first task was the stiffening of morale, and he undertook a course of sharp training on the Scipionic model. Finding the slippery Jugurtha no easy conquest, he attacked the problem in workmanlike manner, by establishing fortified strongholds throughout eastern Numidia and nibbling at the centres of the King’s support. But public opinion at Rome demanded quicker results. Marius himself, returning from Numidia, was elected consul for 107 after a lightning campaign, and was clearly expected to make short work of the troublesome Jugurtha. A speech by Marius, on the morrow of the elections, as reported by the historian Sallust, emphasised his `professionalism’ in contrast with his predecessors in command. In order to increase his forces, Marius called for volunteers from the capite censi, i. e. those assessed in the census by a head-count, and who, lacking any property, were normally excluded from service under the old Servian Constitution. 1 It is difficult to assess the total numbers of capite censi in the citizen body by the later second century, but they seem likely to have formed a substantial group. Marius also persuaded many time-served veterans to join him.

Transporting his forces to Africa, Marius made gradual progress, but found the same difficulty as Metellus in pinning down Jugurtha. At last, with newly arrived cavalry increasing his mobility, and Jugurtha more and more hemmed in by Roman garrisons across the country, the war was brought to a conclusion in 105, when Jugurtha was betrayed to the quaestor L. Cornelius Sulla. Transported to Rome, he was eventually paraded at Marius’ well-deserved Triumph in 104.