As was to be expected in an alliance based on democracy and commercial opportunities, there was open competition in the very lucrative aircraft market, especially for fighters. Challenging the overwhelming industrial might of the United States was always a daunting experience, however, and was frequently both frustrating and very expensive too.

Quite by chance, the start of the Cold War coincided with the advent of the jet age, and competition between the Warsaw Pact and NATO spurred a frantic pace of advance in aircraft technology, as each side sought to achieve an advantage over the other. In the late 1940s all Western air forces were equipped with predominantly propeller-driven combat aircraft, but everyone understood very clearly that these had been outdated at a stroke by the invention of the turbojet engine. Among the Western powers, only two – the United States and the United Kingdom – had viable aircraft design and production facilities, but even for them the first priority was to dispose of their massive stocks of obsolescent and obsolete aircraft, to help pay for the state-of-the-art jet aircraft they needed for their own air forces. For both the US and the UK (as well as for the Soviets on the other side of the Iron Curtain) their existing wartime aircraft industries were a valuable starting point, although the wealth of research data they had captured from the Germans in 1945 was to prove of inestimable value.

FIGHTER AND ATTACK-AIRCRAFT DEVELOPMENT

The USA

The United States’ first operational turbojet fighter was the straight-wing F-80 Shooting Star, deliveries of which started in 1945, just too late to see service in the Second World War. It had a maximum speed of about 950 km/h – little better than the last of the propeller-driven fighters – and survived long enough to become heavily involved in the early days of the Korean War. It was, however, quickly succeeded by the F-84 Thunderjet, also with a straight wing, but with a much higher performance. Some 3,600 of these were built, many of which were exported to NATO countries in the early 1950s.

Design of the first swept-wing interceptor, the F-86 Sabre, began in 1945, with the first prototype flying in 1946 and service deliveries starting in 1948 – a rate of progress that would have been inconceivable thirty years later. The F-86 was the most successful fighter of its day and, with a maximum speed of just over 1,000 km/h and armed with a mixture of guns and rockets, it proved superior to the Soviet MiG-15, which it met in combat in the skies over Korea. The F-86 also became widely used in NATO, being produced in Canada and Italy as well as the United States. Even the UK, which was suffering a delay in production of British-designed fighter aircraft, was forced to operate a number in the early 1950s. Also widely used at this time was the F-84F, which had been created by fitting swept wings to the F-84 Thunderjet, in place of the earlier straight wings; some 2,713 were built, again, many of them for NATO countries.

Meanwhile, intense efforts were being made to exceed the speed of sound, which was eventually achieved in October 1947. Thereafter numerous fighters were able to exceed Mach 1 in a dive, but in 1949 a programme was started to develop the first operational fighter capable of exceeding the speed of sound in level flight.

During the late 1940s the pace of these and many other development programmes both in the USA and the UK was as rapid as peacetime conditions allowed, but when the Korean War broke out, and in particular when the MiG-15 was encountered, all military programmes, especially those involving new technology, were greatly accelerated. The F-100 Supersabre programme was one of those affected; the first flight took place in May 1953, and production aircraft, which had a maximum speed of 1,390 km/h, began to reach squadrons in October of that year. Unfortunately, as happened in many of the programmes rushed through in the early 1950s, the aircraft hit snags and had to be grounded in November 1954 to enable major modifications to be carried out. By the time production ended, however, 2,294 had been produced and the type had been sold to several NATO air forces. It started to leave service in the mid-1960s, but remained with the US air force long enough to take part in the Vietnam War.

In the early 1950s there was rising concern in the USA that the Soviets were developing long-range bombers which would be capable of reaching the continental United States. This led to a requirement for a high-performance interceptor, and the resulting F-102 Delta Dagger became the only delta-winged fighter to operate with the USAF and the first to be designed as a ‘weapon system’, where the aircraft became relatively less important than the avionics that controlled it. Work started in 1952 and the first prototype flew in October 1953, when it exhibited very disappointing flying characteristics, leading to a total redesign. The revised design proved satisfactory and was placed in production, with 875 single-seat fighters and 63 two-seat trainers being delivered within twenty-one months.

The F-102 design was modernized to produce its replacement, the F-106 Delta Dart, which entered service in 1959, but only after further and lengthy development problems. Once these were solved the F-106 served as the continental USA’s only manned interceptor, the last squadron standing down in 1991, exactly thirty years after production had ceased.

The McDonnell F-4 Phantom fighter was designed for the US navy and Marine Corps as a carrier-borne aircraft, but went on to become one of the most successful of all Cold War Western land-based fighters. The naval version first flew in 1958 and entered service in 1961; then, following its adoption by the USAF, the first land-based version flew in 1963. The F-4 was an outstanding design, with a maximum speed at altitude of 2,400 km/h (Mach 2.27) and a ceiling of approximately 20,000 m, outperforming not only other US fighters in the 1960s, but also the Soviet fighters it met over North Vietnam. At one stage production was running at a remarkable seventy-five aircraft per month, and the F-4 was used by numerous NATO air forces: 2,612 were delivered to the USAF, 263 to West Germany, 170 to the UK, 12 to Spain, and 8 each to Greece and Turkey (who both subsequently received a large number of surplus F-4s from West Germany).

During the course of the Cold War there were periodic revulsions against the seemingly inexorable increase in the complexity and cost of fighter aircraft. One outcome of such a feeling was the Northrop F-5 Freedom Fighter, which was designed as a simpler and cheaper, but nevertheless high-performance, alternative. It was funded by the company and first flew in 1959, but it attracted only a relatively few orders from the US air force. Despite this, the type sold well overseas, including to several NATO air forces.

The General Dynamics F-111 started life as the TFX (Tactical Fighter, Experimental) programme in an effort to produce a long-range, high-performance attack aircraft which would meet the needs of the US navy, Marine Corps and air force, and which would also, it was hoped, obtain large overseas orders. The key design feature of the F-111 was its swing wing, and the programme started in 1960, with the first flight in 1964 and initial service delivery in 1967. From the start, however, the programme was beset by problems, which ranged from excessive aerodynamic drag, through ever-escalating weight and cost, to inter-service rivalry. The problems were eventually overcome, and the F-111 fighter and the FB-111 strategic-bomber version became very successful and capable aircraft, although they were only ever purchased by the air force. The FB-111 was also due to have been ordered by the British air force in place of the abandoned TSR-2, but this order was cancelled and the only overseas order was for twenty-four from Australia.

Another 1960s aircraft, the A-7 Corsair II light attack aircraft, was designed for carrier operations with the US navy and Marine Corps, but then, like the F-4 Phantom, it was adopted by the air force as well. The first flight was in 1965, and the Corsair II showed a realization that supersonic performance was not necessary for a tactical fighter. The type also served with other NATO air forces, Greece purchasing sixty-five and Portugal twenty.

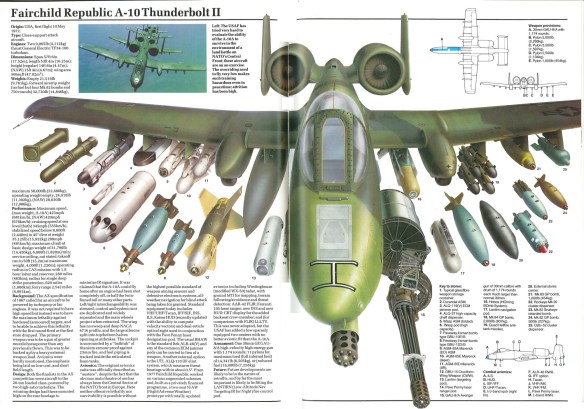

The Fairchild A-10 Thunderbolt was designed to meet a USAF requirement (known as ‘AX’) for a highly capable but low-cost ground-attack aircraft, which would provide a very heavy ‘punch’ enabling it to destroy large numbers of Warsaw Pact tanks. This necessitated an extremely strong air-frame and armoured protection for the pilot, to enable both to survive at low altitude above the European battlefield. The aircraft was also required to operate from and be maintained at forward bases with limited facilities. Having won the AX competitive fly-off, the A-10 was placed in production and entered service in 1977, with a total of 707 being produced, all for the USAF; there were no export orders. Main armament was a seven-barrelled 30 mm gun, plus 7,247 kg of ordnance on eleven pylons.

The F-15 Eagle air-superiority fighter was the successor to the F-4 Phantom, with the first flight in 1972 and service delivery in 1974, following which the type served as the main USAF fighter for the remainder of the Cold War and beyond. With a maximum speed of 2,655 km/h (Mach 2.5), it climbed to 15,240 m in 2.5 minutes and, while it was an outstanding interceptor fighter, it was also adapted to the attack mission. The aircraft and its back-up systems were, however, so expensive that no NATO orders were forthcoming.

Yet another attempt was made to reduce the costs of fighter aircraft in the late 1960s, this time with considerable success, as the outcome was the General Dynamics F-16 Fighting Falcon. This started life as the YF-16 lightweight fighter for the US air force, but it was then developed by the company and proved so sound a design that it quickly evolved, first into a ‘no-frills’ interceptor, and subsequently into a very effective multi-role fighter. It was ordered for the US air force in 1975, with 2,795 being delivered; others, as described below, were ordered by other NATO countries. The F-16 was armed with a 20 mm Vulcan cannon and carried 5,420 kg of ordnance if the aircraft was to be manoeuvred at its maximum of 9g, but an even greater load was possible if restrictions on manoeuvrability were imposed.