At that point Hitler himself intervened and fixed zero hour at “sunrise minus 30 minutes”. Numerous test flights had shown that to be the earliest moment at which the glider pilots would have enough visibility.

So it was that the whole German Army had to take its time from a handful of “adventurers” who had the presumption to suppose that they could subdue one of the world’s most impregnable fortresses from the air.

At 03.10 hours on May 10th the field telephone jangled at the command post of Major Jottrand, who was in charge of the Eben Emael fortifications. The 7th Belgian Infantry Division, holding the Albert Canal sector, imposed an increased state of alert. Jottrand ordered his 1,200-strong garrison to action stations. Sourly, for the umpteenth time, men stared out from the gun turrets into the night, watching once again for the German advance.

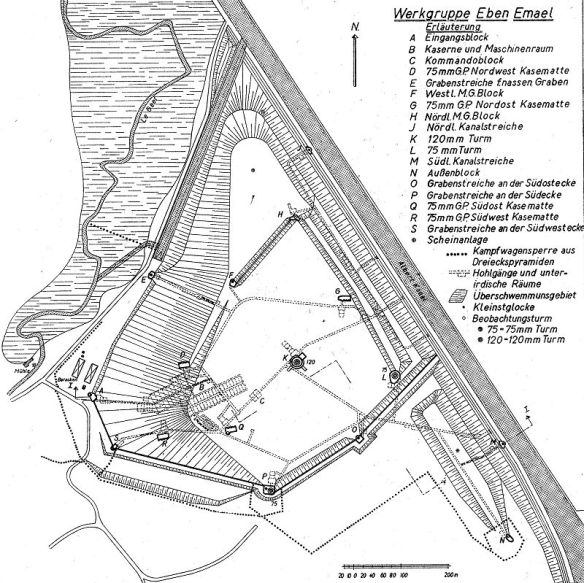

For two hours all remained still. But then, as the new day dawned, there came from the direction of Maastricht in Holland the sound of concentrated anti-aircraft fire. On Position No. 29, on the south-east boundary of the fortress, the Belgian bombardiers raised their own anti-aircraft weapons. Were the German bombers on the way? Was the fortress their objective? Listen as they might, the men could hear no sound of engines.

Suddenly from the east great silent phantoms were swooping down. Low already, they seemed to be about to land: three, six, nine of them. Lowering the barrels of their guns, the Belgians let fly. But next moment one of the “great bats” was immediately over them—no, right amongst them!

Corporal Lange set his glider down right on the enemy position, severing a machine-gun with one wing and dragging it along. With a tearing crunch the glider came to rest. As the door flew open, Sergeant Haug, in command of Section 5, loosed off a burst from his machine-pistol, and hand-grenades pelted into the position. The Belgians held up their hands.

Three men of Haug’s section scampered across the intervening hundred yards towards Position 23, an armoured gun turret. Within one minute all the remaining nine gliders had landed at their appointed spots in the face of machine-gun fire from every quarter, and the men had sprung out to fulfill their appointed duties.

Section 4’s glider struck the ground hard about 100 yards from Position 19, an anti-tank and machine-gun emplacement with embrasures facing north and south. Noting that the latter were closed, Sergeant Wenzel ran directly up to them and flung a 2-lb. charge through the periscope aperture in the turret. The Belgian machine-guns chattered blindly into the void. Thereupon Wenzel’s men fixed their secret weapon, a 100-lb. hollow charge, on the observation turret and ignited it. But the armour was too thick for the charge to penetrate: the turret merely became seamed with small cracks, as in dry earth. Finally they blew an entry through the embrasures, finding all weapons destroyed and the gunners dead.

Eighty yards farther to the north Sections 6 and 7 under Corporals Harlos and Heinemann had been “sold a dummy”. Positions 15 and 16—especially strong ones according to the air pictures—just did not exist. Their “15-foot armoured cupolas” were made of tin. These sections would have been much more useful further south. There all hell had broken loose at Position 25, which was merely an old tool shed used as quarters. The Belgians within it rose to the occasion better than those behind armour, spraying the Germans all round with machine-gun fire. One casualty was Corporal Unger, leader of Section 8, which had already blown up the twin-gun cupola of Position 31.

Sections 1 and 3, under N.C.O.s Niedermeier and Arent, put out of action the six guns of artillery casements 12 and 18. Within ten minutes of “Granite” detachment’s landing ten positions had been destroyed or badly crippled. But though the fortress had lost most of its artillery, it had not yet fallen. The pillboxes set deep in the boundary walls and cuttings could not be got at from above. Observing correctly that there were only some seventy Germans on the whole plateau, the Belgian commander, Major Jottrand, ordered adjoining artillery batteries to open fire on his own fort.

As a result the Germans had themselves to seek cover in the positions they had already subdued. Going over to defence, they had to hold on till the German Army arrived. At 08.30 there was an unexpected occurrence when an additional glider swooped down and landed hard by Position 19, in which Sergeant Wenzel had set up the detachment command post. Out sprang First-Lieutenant Witzig. The replacement Ju 52 he had ordered had succeeded in towing his glider off the meadow near Cologne, and now he could belatedly take charge.

There was still plenty to do. Recouping their supplies of explosives from containers now dropped by Heinkel 111s, the men turned again to the gun positions which had not previously been fully dealt with. 2-lb. charges now tore the barrels apart. Sappers penetrated deep inside the positions and blew up the connecting tunnels. Others tried to reach the vital Position 17, set in the 120-foot wall commanding the canal, by suspending charges on cords.

Meanwhile hours passed, as the detachment waited in vain for the Army relief force, Engineer Battalion 51. Witzig was in radio contact both with its leader, Lieutenant-Colonel Mikosch, and with his own chief, Captain Koch at the Vroenhoven bridgehead. Mikosch could only make slow progress. The enemy had successfully blown the Maastricht bridges and indeed the one over the Albert Canal at Kanne—the direct connection between Maastricht and Eben Emael. It had collapsed at the very moment “Iron” detachment’s gliders approached to land.

On the other hand the landings at Vroenhoven and Veldwezelt had succeeded, and both bridges were intact in the hands of the “Concrete” and “Steel” detachments. Throughout the day all three bridgeheads were under heavy Belgian fire. But they held—not least thanks to the covering fire provided by the 88-mm batteries of Flak Battalion “Aldinger” and constant attacks by the old Henschel Hs 123s of II/LG 2 and Ju 87s of StG 2.

In the course of the afternoon these three detachments were at last relieved by forward elements of the German Army. Only “Granite” at Eben Emael had still to hang on right through the night. By 07.00 the following morning an assault party of the engineer battalion had fought its way through and was greeted with loud rejoicing. At noon the remaining fortified positions were assaulted, then at 13.15 the notes of a trumpet rose above the din. It came from Position 3 at the entrance gate to the west. An officer with a flag of truce appeared, intimating that the commander, Major Jottrand, now wished to surrender.

Eben Emael had fallen. 1,200 Belgian soldiers emerged into the light of day from the underground passages and gave themselves up. In the surface positions they had lost twenty men. The casualties of “Granite” detachment numbered six dead and twenty wounded.

One story remains to be told. The Ju 52s, having shed the gliders of “Assault Detachment Koch”, returned to Germany and dropped their towing cables at a prearranged collection point. Then they turned once more westwards to carry out their second mission. Passing high over the battle- field of Eben Emael they flew on deep into Belgium. Then, twenty-five miles west of the Albert Canal they descended. Their doors opened and 200 white mushrooms went sailing down from the sky. As soon as they reached the ground, the sound of battle could be heard. For better or worse the Belgians had turned to confront the new enemy in their rear.

But for once the Germans did not attack. On reaching them the Belgians discovered the reason: the “paratroops” lay still entangled in their ‘chutes. They were not men at all, but straw dummies in German uniform armed with self-igniting charges of explosive to imitate the sound of firing. As a decoy raid, it certainly contributed to the enemy’s confusion.