Scharnhorst and Gneisenau were powerful armoured cruisers, enlarged and improved versions of the earlier ‘Roon’ class, completed in 1907-8.

Battle of the Falkland Islands by Randall Wilson. (Y) Admiral von Spees Flagship SMS Scharnhorst leads SMS Gneisenau in the opening stages of engaging the Royal Naval ships east of the Falklands, 8th December 1914.

From 1911, they were deployed to Tsingtao in China, to form the spearhead of the German Asiatic Squadron under Admiral von Spee. The squadron sailed east for home waters on the outbreak of World War I, and destroyed the British South Atlantic Squadron at Coronel off the Chilean coast. Rounding Cape Horn, the squadron raided the Falklands, but encountered a strong British naval force that included the battlecruisers Inflexible and Invincible. After a three-hour running fight Scharnhorst went down with all hands: Gneisenau was battered into a blazing wreck and sank soon afterwards.

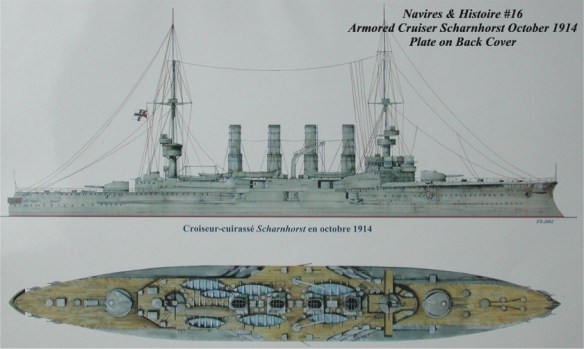

The Germans continued to expand their cruiser force in part from their continued faith in armored cruisers, which was reinforced by the Japanese success in the Russo-Japanese War. These two vessels of the Scharnhorst-class, laid down between 1904 and 1905 and launched in 1907 and 1908 respectively, measured 474 feet, 9 inches by 71 feet and displaced 12,781 tons. Each ship carried a primary armament of eight 8.2- inch guns; four were mounted in two two-gunned turrets located fore and aft, while the others were mounted in broadside within casemates located amidships. They were also armed with six 6-inch guns and four 18-inch torpedo tubes. The ships’ armor, which consisted of a belt with a maximum thickness of 6 inches and deck protection of 2 inches, was much the same as the Roon-class launched earlier. Their engines could produce a maximum speed of 23.5 knots. The country’s cruiser program also continued to produce light cruisers as a result of the German belief that arose at the turn of the twentieth century in light cruisers as multipurpose warships that could serve both with the fleet and as commerce raiders. Germany completed the construction of the last two Bremen-class light cruisers in 1906 and 1907 respectively. They also laid down four ships of the Königsburg-class and two Dresden-class light cruisers between 1905 and 1908. These vessels were essentially larger and faster versions of the Bremen-class that incorporated the same armament as their predecessors but with less deck armor.

THE BATTLE OF CORONEL

In August 1914 Vice-Admiral Graf Maximilian von Spee commanded a small squadron of German warships, led by the armoured cruisers SMS Scharnhorst and SMS Gneisenau, which was located at the Caroline Islands in the western Pacific. From the outbreak of war von Spee was given a free hand by Berlin, and he set off to patrol the shipping lanes off the coast of South America in search of Allied vessels.

Also at sea in that area was Rear-Admiral Sir Christopher Cradocks’ South Atlantic Squadron, which consisted of three elderly cruisers HMS Good Hope, HMS Monmouth and HMS Glasgow along with the armed merchant ship Otranto. Von Spee’s six warships threw a much heavier broadside that the Royal Navy ships, particularly Scharnhorst and Gneisenau which both mounted eight 21cm and six 15cm guns. Cradock was aware of the presence of von Spee’s squadron and he was ordered to try and find it and to “be prepared to meet them in company”, which he took to mean that he should engage the German ships even though he would be heavily outgunned.

What was described as “tempestuous” weather in the South Atlantic had been raging for many days at the end of October and on 1 November, Cradocks’ buffeted ships were spread over fifteen miles of heavy seas. That afternoon von Spee’s squadron was sighted approximately forty miles west of the Chilean port of Coronel.

Cradock could have avoided battle, as his ships were marginally faster than those of the Germans and the old battleship HMS Canopus, with its 12-inch guns, was on its way to join him. However, had he waited, Cradock would have let the Germans escape. So he issued the order, “I am going to attack now!”

Von Spee recorded the battle as it unfolded: “At 6.39 the first hit was recorded on the Good Hope, and shortly afterwards the British opened fire. I am of opinion that they suffered more from the heavy seas than we did. Both their armoured cruisers, with the shortening of range and the falling light, were practically covered by our fire, while they themselves, so far as can be ascertained at present, only hit the Scharnhorst twice and the Gneisenau four times. At 6.53, when at a distance of sixty hectometres, I sheered off a point.” (The times here are those maintained by the Germans which were actually about thirty minutes behind local time.)

The third salvo from Scharnhorst ignited the cordite charges of HMS Good Hope’s main armament and flames spread along the warship. HMS Monmouth was also soon on fire. Eventually, with the British ships unable to defend themselves, von Spee moved in and shelled the ships until both sank. Because of the heavy seas, no attempt was made to rescue survivors and all 1,570 men of the two British ships died. Glasgow and Otranto both escaped. The Germans had just three men wounded. The Royal Navy, however, extracted its revenge on 8 December 1914.

THE BATTLE OF THE FALKLAND ISLANDS

Still reeling from the defeat at the Battle of Coronel, the Admiralty despatched a large Royal Navy force to intercept the victorious German cruiser squadron. After their decisive victory, the German warships, under Vice-Admiral Graf Maximilian von Spee, had been ordered to head for home.

Von Spee, however, decided to make one “call” on the way – at Port Stanley in the Falkland Islands. His intention had been to destroy the radio station located there and take the Governor prisoner as an act of a reprisal for the British capture of the German governor of Samoa.

Unknown to Admiral Spee as he headed for the Falklands, a British naval squadron, including the two battlecruisers HMS Invincible and HMS Inflexible, had arrived there on Monday, 7 December 1914. This force also contained HMS Carnarvon (an improved Devonshire-class armoured cruiser), the Monmouth-class armoured cruisers Cornwall and Kent, HMS Bristol (a Town-class light cruiser) and the armed merchant cruiser HMS Macedonia. All were under the command of Admiral Frederick Charles Doveton Sturdee.

The morning of 8 December 1914, however, found the entire British force, with only the odd exception, at anchor and busy coaling. They were very nearly caught out.

The obsolete pre-dreadnought battleship HMS Canopus had been moored (in fact it was resting on the mud) in such a position as to command the entrance to the harbour at Stanley. Hidden from German view behind a hill, when the enemy warships were sighted, Canopus opened fire. Her actions were enough to check the German cruisers’ advance. To many she had ultimately ensured British success in the coming battle.

Had the Germans attacked at this point, the British warships would be stationary targets. If any warship was sunk whilst leaving port, the rest of the squadron would be trapped.Sturdee, however, kept calm, ordered steam to be raised and then went and had breakfast.

The sight of the masts of the British battlecruisers confirmed to the Germans that they were facing a better equipped enemy. HMS Kent, which was already making way out of the harbour, was ordered to follow them as they turned away.

“The men smacked about splendidly and things fairly hummed,” recalled Engineer Lieutenant Commander J. Fraser Shaw on HMS Invincible. “We got our oil fuel ready at once and as soon as any boiler was lit we smacked the oil fuel in at once. The result was that about 9.50 or 9.55am we started moving – and by 10.10 were going 18 knots.” The chase was on.

“We are almost sure that one of our first shots struck the Nürnberg in the stern as she dropped out of line quite early on,” continued Shaw. “When the [enemy] line broke up, the Inflexible, ourselves and Carnarvon went after the Scharnhorst and the Gneisenau who kept together. The Kent went for the Nürnberg and sank her and we heard later that the Glasgow and Cornwall sank the Leipzig between them.”

Realising that they were unable to escape the pursing Royal Navy warships, Scharnhorst and Gneisenau turned to fight, letting their escorting light cruisers slip away. In the face of the accurate British bombardment, Scharnhorst soon received over fifty hits, three funnels were down, and she was on fire and listing.The range kept falling and at 16.04 hours, Scharnhorst listed suddenly to port. Just thirteen minutes later she had disappeared.

Whilst Scharnhorst was sinking, Gneisenau had continued to fire. She was able to evade the British until 17.15 hours by which time her ammunition was exhausted. Gneisenau sank at 18.02 hours; just 190 survivors were rescued from the water.

Nürnberg, meanwhile, was still running at full speed, the crew of the pursuing HMS Kent was pushing its boilers and engines to the limit. Nürnberg finally turned to battle at 17.30 hours. Kent had the advantage in shell weight and armour. Nürnberg suffered two boiler explosions an hour later, giving the advantage in speed and manoeuvre to Kent. After a long chase Nürnberg rolled over and sank at 19.27 hours.

The cruisers Glasgow and Cornwall had also chased down Leipzig. Glasgow closed to finish the German warship which had run out of ammunition. When the latter fired two flares, Glasgow halted fire. At 21.23 hours, at a spot more than eighty miles south-east of the Falkland Islands, Leipzig also rolled over,

The Battle of the Falkland Islands had been a decisive confrontation. Not one of the British warships was sunk – let alone badly damaged. Just ten British sailors or Marines were killed and a further nineteen wounded.

By contrast, the German force had been ravaged. Some 1,871 German sailors were killed in the encounter, including Admiral Spee and his two sons. A further 215 survivors were rescued. Not one of the 765 officers and men from the Scharnhorst survived. Of the known German force of eight ships, only two escaped: the auxiliary Seydlitz and the light cruiser Dresden.

The most important outcome of the battle, however, was the fact that commerce raiding on the high seas by regular warships of the Imperial German Navy came to an abrupt end, leaving just eighteen survivors.

Displacement: 11,600t standard, 12,900t full load

Dimensions: 144.6m x 21.6m x 7.9m (474ft 4in x 70ft 10in x 26ft)

Machinery: three screws, vertical triple expansion engines; 26,000hp

Armament: eight 210mm (8.25in) guns; six 150mm (5.9in) guns; four 450mm (17.7in) TT

Armour: belt 150-80mm (5.9-3.2in); turrets 170mm (6.6In); deck 60mm (2.3in)

Speed: 22.5 knots

Range: 9487km (5120nm) at 12 knots

Complement: 764